City or suburbs: Where can you afford to live?

We crunched the numbers so you can decide

Advertisement

We crunched the numbers so you can decide

Two years ago, Jennifer and Glen Leblonc decided they were done with city living. From a practical standpoint, their family had outgrown their 1,200-square-foot condo in downtown Montreal. And the space, already overrun with their two-year-old son’s toys and gear, was only going to get more crowded with a second child on the way. Plus, a move would help them escape the nuisance neighbour who would pound on the wall whenever their son made noise. It was time to move to the suburbs.

“When we lived in the condo, we were both home by 4:15,” says Jennifer. Every other day they walked two blocks to the grocery store to pick up a few things and they’d often spend evenings or weekends strolling the canal, playing in one of many nearby parks or wandering through the outdoor markets. These days, Glen is lucky to spend an hour with his kids after work before they’re off to bed (Jennifer is still on maternity leave). And on weekends, it’s a crunch to get groceries and clean the house so they can spend time together as a family.

“When we lived in the condo, we were both home by 4:15,” says Jennifer. Every other day they walked two blocks to the grocery store to pick up a few things and they’d often spend evenings or weekends strolling the canal, playing in one of many nearby parks or wandering through the outdoor markets. These days, Glen is lucky to spend an hour with his kids after work before they’re off to bed (Jennifer is still on maternity leave). And on weekends, it’s a crunch to get groceries and clean the house so they can spend time together as a family.

“We moved to give our kids a better lifestyle,” says Jennifer. “We discovered we had more family time when we lived downtown.”

Each year, home buyers across North America struggle with a familiar choice: They can pay more to live in a smaller urban property, within walking distance to schools, shops and work; or pay less for a larger suburban home with a big backyard and ample parking, but have to hop in a car for just about everything they need. At first blush, it appears urban and suburban residents may simply have fundamentally different values and interests, but that may not be the case. For many Canadians, the decision between city and suburb boils down to how strongly you weight three important factors—your money, your time and your overall lifestyle. No two families prioritize these in exactly the same way. Moreover, even the urban-suburban truths we hold to be self-evident—as in, it’s always cheaper to live in the suburbs—don’t tell the entire tale.

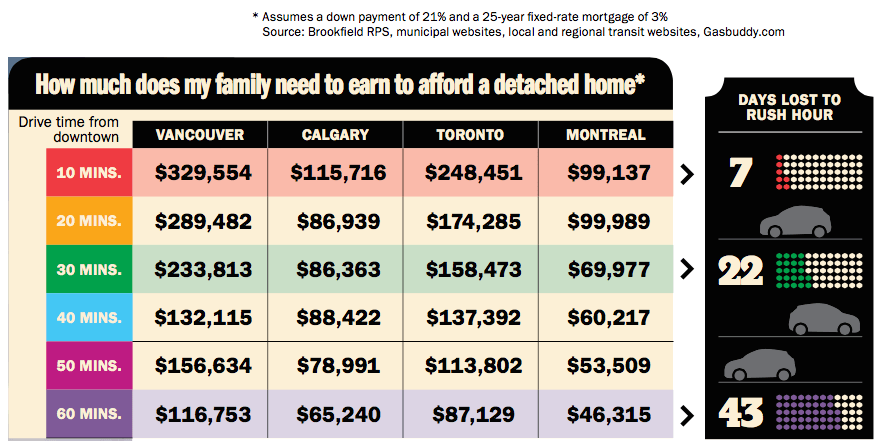

To help readers appreciate this important decision, MoneySense teamed up with real estate analysts Brookfield RPS to explore what it means to own and live in a single-family detached home within or near each of Canada’s four largest cities: Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto and Montreal. Detailed data on commute times, current average sale prices, living space and lot sizes—including a tricky calculation to tell us how much of a home’s value is currently locked into the land itself—were divided into layers spreading out from each downtown centre (we used City Hall to keep things consistent). Each ring represents 10 minutes of non-rush-hour driving. Armed with this data, we can tell you just how much home and property you can expect to find the further you drive from downtown. Moreover, we can tell you how much it actually costs to live in each respective layer, factoring in average annual transit costs and property taxes. In other words, we did what MoneySense does best: We calculated firm figures to guide an important financial decision—in this case, one of the most important and emotional ones a person or family can make.

Some of our suspicions were confirmed: By and large, suburban homes are priced cheaper compared to urban homes. But there were surprises, too. Of the four cities we looked at, Toronto is the only one where homes 20 minutes from the city core are smaller—by an average of 12%—than homes right downtown; Calgarians end up paying roughly the same price-per-square-foot for their living space whether they buy 30 or 60 minutes from the city centre; and in Vancouver, it can be more costly to live 50 minutes out than it is to live closer to downtown. (In all cases, we focused on data for single-family, detached homes.)

Of course, home prices are far from the only factor home owners consider. The time spent commuting, along with lifestyle preferences and proximity to amenities complicate matters. While this decision is often seen as a trade-off—where one factor tips the scales over another—in reality, it’s more like finding a sweet spot, a delicate balance between cost and commuting time and how close you are to friends, family and amenities. It’s the place where building a family home is an act of love, not a mathematical science. What the Lebloncs miss about living in downtown Montreal—the ability to share a coffee with friends or stroll the neighbourhood with their kids—is exactly what Christine and Paul McIntyre-Royston love about their Calgary suburb of Auburn Bay. Last year, after living in Renfrew, an inner-city Calgary community, the McIntyre-Roystons moved 50 minutes south to their new three-bedroom home, complete with idyllic backyard and a community-access lakeside cottage with canoes, tennis courts and party room. Paul is the president and CEO of the Calgary Public Library Foundation, while Christine is a stay-at-home mom. “Every single house has kids,” says Paul. “It has such a tremendous community feel.” For the McIntyre-Roystons, space was the biggest reason they looked at buying a suburban home. “Our old house had about 1,000 square feet of living space,” says Christine. “There were only two bedrooms and we already had two daughters, with a third on the way.” They loved their inner city neighbourhood, but Calgary real estate was hot in 2014 and they found many homes were beyond their budget. So, they opted to stretch their commute to get more house. The savings can be significant. In Calgary, a property located a 10-minute drive away from city hall will cost just over $123 a square foot. Increasing your commute to 30 minutes drops the square-foot cost for the land to $31. (In Toronto, the same scenario would take you from $375 per square foot of land down to $123.) Bluntly put: This has a real impact on a homebuyer’s bottom line.

Based on our calculations, with a down payment of 21% (the national average), a 25-year amortized mortgage and an interest rate of 3%, a family needs a gross household income of at least $116,000 in order to afford a single-family detached home in Calgary’s city centre. That’s a bargain given that at current prices it takes a combined annual salary of $248,000 to afford a detached home in downtown Toronto. While the GTA is awash in condos, detached homes still account for half of all sales in the region, according to the Toronto Real Estate Board. Move to the 30-minute commuter band—roughly Scarborough or Mississauga—and the income required drops to just under $158,000.

In most cities across Canada, the premium to purchase a suburban-sized lot in an urban setting is beyond the reach of an average family. By our calculations, a downtown Vancouver home buyer would have to shell out roughly $3.3 million, for a property similar in size to what they could buy for half that price in Coquitlam, about a half-hour drive away. Transplant a home from Mississauga into Toronto’s urban core and it would fetch close to $2.24 million, about $700,000 higher than what the average downtown home sold for in 2015.

While affordability is important, there are other factors to consider. Larry Carloni, who currently resides in Gibsons, B.C., with his wife Kathryn, began to discuss the possibility of moving back to Calgary when his mom fell ill. “I grew up in the Haysboro community and I have such good memories,” says Larry. Based on their budget, they began looking at homes further from the city centre, but Larry wasn’t impressed with the options. “The homes that were more affordable were older, while the newer ones were just narrow rooms stacked on top of each other and built only a few feet away from the neighbour.” That’s when Larry and Kathryn looked to Okotoks, a community 40 minutes south of Calgary. “The home prices aren’t that different, but you can buy a newer, one-level home on a bigger lot and you have all the amenities you need for a normal life without the big city inconveniences.” One of those inconveniences, says Larry, is something he calls “the waiting game.” As in, a quick trip to the mall gets quickly kiboshed when you spend 20 minutes circling the parking lot.

Some of the city dwellers we spoke with were likewise shocked at how weekly, monthly or even one-off chores can take over a weekend when living downtown. While it’s true that many needs can be met by simply walking to the corner store or a nearby market, bigger tasks—such as getting material to hang shelves, getting everything on that large grocery list or completing your family’s back-to-school shopping—often requires a car, time and patience. There are relatively fewer large grocery stores within the city core—and even fewer big box stores. (In fact, that’s part of the appeal for diehard downtowners.) But for those living in the suburbs, where SmartCentres and strip malls are plentiful, it can be easier to complete mundane errands quickly and efficiently, leaving extra time to spend with family.

For the McIntyre-Roystons, the move to Auburn meant some big changes to their lifestyle as well. “We no longer pick things up on the way home from work. We make a meal plan, use grocery lists and shop once per week,” says Christine. But where their food budget shrank, their gas allowance grew. These days, Christine drives a mini-van while Paul uses the second-hand Smart car. “It’s good on gas, which is why we bought it,” says Paul. That’s good, since Paul’s commute has doubled. It’s even longer if he leaves the house later than 6:30 a.m.

While Calgary commuters like Paul pay approximately $3,000 each year for gas and parking, home owners in other cities can expect to pay much more to commute, even if they don’t drive. Using today’s transit rates, a couple commuting 30 minutes (in non-rush hour traffic) one-way to Toronto’s downtown core could pay upwards of $6,000 each year, assuming optimal use of GO Train’s Presto card and TTC tokens. According to a report from the Centre for Economics & Business Research, that same couple will need to budget $1,260 more for commuting costs by the year 2030.

Even more shocking than the expense of commuting is the time spent travelling to and from work. According to our calculations a 10-minute commute to work (which, let’s be honest, is really 20 minutes during rush hour) is the equivalent of spending seven full days in transit each year. Increase that commute time to 60 minutes (or up to two hours each way during peak travel times) and you’re looking at 43 days spent in traffic. Of course, not every family has two commuters travelling downtown each day. One partner may work from home, or commute in another direction; this will greatly impact a family’s budget and schedule.

To get away from these long commute times, many Canadians are opting for walkable communities that offer nearby shopping, work, transit and amenities. Known in city-planner speak as “complete neighbourhoods,” these walkable neighbourhoods can be found in both urban and suburban settings. Just ask Alex Fuller. She doesn’t work in one of the four major cities we studied (Fuller works in Guelph, Ont., in human resources), but she did end up choosing to live in a suburb of Toronto—and ironically found the walkable neighbourhood she craved. As a single mom it was important for her to stay near family and friends, most of whom live in or near Burlington, Ont., about a 45-minute drive west of the city. She also wanted the ability to ditch her car on the weekends. “I wanted to raise my son with the convenience of downtown walkability but without the negative big-city influences,” such as drug-related crime and urban nightlife. So, she bought a cozy, detached home on a large lot in this bedroom city’s downtown.

Over the years her home became a hub. “Since we live so close to downtown, everyone meets and parks at my place. Then we all walk to where we want to go,” says Fuller. The location was great for her son. “The big backyard, coupled with a detached garage that we turned into a man cave, meant my house became the place to hang out—and that meant I could keep an eye on my boy without intruding on his space,” she says.

Fuller’s 45-minute commute to Guelph (she now works closer to home) sometimes made for stressful time when managing home and hockey schedules. To make it work, she had to arrange for a backup plan. “I was fortunate,” she says. “I can’t imagine what it would’ve been like to commute, get stuck and not have help.”

The savings can be significant. In Calgary, a property located a 10-minute drive away from city hall will cost just over $123 a square foot. Increasing your commute to 30 minutes drops the square-foot cost for the land to $31. (In Toronto, the same scenario would take you from $375 per square foot of land down to $123.) Bluntly put: This has a real impact on a homebuyer’s bottom line.

Based on our calculations, with a down payment of 21% (the national average), a 25-year amortized mortgage and an interest rate of 3%, a family needs a gross household income of at least $116,000 in order to afford a single-family detached home in Calgary’s city centre. That’s a bargain given that at current prices it takes a combined annual salary of $248,000 to afford a detached home in downtown Toronto. While the GTA is awash in condos, detached homes still account for half of all sales in the region, according to the Toronto Real Estate Board. Move to the 30-minute commuter band—roughly Scarborough or Mississauga—and the income required drops to just under $158,000.

In most cities across Canada, the premium to purchase a suburban-sized lot in an urban setting is beyond the reach of an average family. By our calculations, a downtown Vancouver home buyer would have to shell out roughly $3.3 million, for a property similar in size to what they could buy for half that price in Coquitlam, about a half-hour drive away. Transplant a home from Mississauga into Toronto’s urban core and it would fetch close to $2.24 million, about $700,000 higher than what the average downtown home sold for in 2015.

While affordability is important, there are other factors to consider. Larry Carloni, who currently resides in Gibsons, B.C., with his wife Kathryn, began to discuss the possibility of moving back to Calgary when his mom fell ill. “I grew up in the Haysboro community and I have such good memories,” says Larry. Based on their budget, they began looking at homes further from the city centre, but Larry wasn’t impressed with the options. “The homes that were more affordable were older, while the newer ones were just narrow rooms stacked on top of each other and built only a few feet away from the neighbour.” That’s when Larry and Kathryn looked to Okotoks, a community 40 minutes south of Calgary. “The home prices aren’t that different, but you can buy a newer, one-level home on a bigger lot and you have all the amenities you need for a normal life without the big city inconveniences.” One of those inconveniences, says Larry, is something he calls “the waiting game.” As in, a quick trip to the mall gets quickly kiboshed when you spend 20 minutes circling the parking lot.

Some of the city dwellers we spoke with were likewise shocked at how weekly, monthly or even one-off chores can take over a weekend when living downtown. While it’s true that many needs can be met by simply walking to the corner store or a nearby market, bigger tasks—such as getting material to hang shelves, getting everything on that large grocery list or completing your family’s back-to-school shopping—often requires a car, time and patience. There are relatively fewer large grocery stores within the city core—and even fewer big box stores. (In fact, that’s part of the appeal for diehard downtowners.) But for those living in the suburbs, where SmartCentres and strip malls are plentiful, it can be easier to complete mundane errands quickly and efficiently, leaving extra time to spend with family.

For the McIntyre-Roystons, the move to Auburn meant some big changes to their lifestyle as well. “We no longer pick things up on the way home from work. We make a meal plan, use grocery lists and shop once per week,” says Christine. But where their food budget shrank, their gas allowance grew. These days, Christine drives a mini-van while Paul uses the second-hand Smart car. “It’s good on gas, which is why we bought it,” says Paul. That’s good, since Paul’s commute has doubled. It’s even longer if he leaves the house later than 6:30 a.m.

While Calgary commuters like Paul pay approximately $3,000 each year for gas and parking, home owners in other cities can expect to pay much more to commute, even if they don’t drive. Using today’s transit rates, a couple commuting 30 minutes (in non-rush hour traffic) one-way to Toronto’s downtown core could pay upwards of $6,000 each year, assuming optimal use of GO Train’s Presto card and TTC tokens. According to a report from the Centre for Economics & Business Research, that same couple will need to budget $1,260 more for commuting costs by the year 2030.

Even more shocking than the expense of commuting is the time spent travelling to and from work. According to our calculations a 10-minute commute to work (which, let’s be honest, is really 20 minutes during rush hour) is the equivalent of spending seven full days in transit each year. Increase that commute time to 60 minutes (or up to two hours each way during peak travel times) and you’re looking at 43 days spent in traffic. Of course, not every family has two commuters travelling downtown each day. One partner may work from home, or commute in another direction; this will greatly impact a family’s budget and schedule.

To get away from these long commute times, many Canadians are opting for walkable communities that offer nearby shopping, work, transit and amenities. Known in city-planner speak as “complete neighbourhoods,” these walkable neighbourhoods can be found in both urban and suburban settings. Just ask Alex Fuller. She doesn’t work in one of the four major cities we studied (Fuller works in Guelph, Ont., in human resources), but she did end up choosing to live in a suburb of Toronto—and ironically found the walkable neighbourhood she craved. As a single mom it was important for her to stay near family and friends, most of whom live in or near Burlington, Ont., about a 45-minute drive west of the city. She also wanted the ability to ditch her car on the weekends. “I wanted to raise my son with the convenience of downtown walkability but without the negative big-city influences,” such as drug-related crime and urban nightlife. So, she bought a cozy, detached home on a large lot in this bedroom city’s downtown.

Over the years her home became a hub. “Since we live so close to downtown, everyone meets and parks at my place. Then we all walk to where we want to go,” says Fuller. The location was great for her son. “The big backyard, coupled with a detached garage that we turned into a man cave, meant my house became the place to hang out—and that meant I could keep an eye on my boy without intruding on his space,” she says.

Fuller’s 45-minute commute to Guelph (she now works closer to home) sometimes made for stressful time when managing home and hockey schedules. To make it work, she had to arrange for a backup plan. “I was fortunate,” she says. “I can’t imagine what it would’ve been like to commute, get stuck and not have help.”

Bear in mind: Calculating these costs required making many assumptions. For example, the commuting and transit costs for suburban homeowners assume one-car per family. Add a second car and you need to factor in gas, parking, insurance and maintenance. Here’s the thing: To get rid of a car and move closer to city transit would save approximately $200,000 over 25 years (the standard length of most mortgages). Those savings might put you in a different house cost bracket, or it could make a difference to you and your family in other ways; perhaps help you afford that dream family vacation or saving for a child’s education.

Finding your sweet spot when it comes to urban-suburban living is not about how much a house costs or how large your yard is—it’s about finding a house that allows you to get to work, run your errands and leaves you with enough time in your day (and money in your wallet) to enjoy your life. Some people will only be truly happy living outside the city, while others are content to pay for less if it gives them more time. That much has always been known, but armed with this data you may find your sweet spot might not be where you expect.

Affiliate (monetized) links can sometimes result in a payment to MoneySense (owned by Ratehub Inc.), which helps our website stay free to our users. If a link has an asterisk (*) or is labelled as “Featured,” it is an affiliate link. If a link is labelled as “Sponsored,” it is a paid placement, which may or may not have an affiliate link. Our editorial content will never be influenced by these links. We are committed to looking at all available products in the market. Where a product ranks in our article, and whether or not it’s included in the first place, is never driven by compensation. For more details, read our MoneySense Monetization policy.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

Can we get the 2021 version of this article please.