Make your bonds inflation-proof

With annual inflation now outpacing the yields on 10-year bonds, you’re losing purchasing power. Time to get ‘real’.

Advertisement

With annual inflation now outpacing the yields on 10-year bonds, you’re losing purchasing power. Time to get ‘real’.

During periods of market turmoil, most investors look for a safe haven. Unfortunately, some of today’s perceived havens can be more exposed than a beach resort in a hurricane.

Let’s start with cash. Today, the net return on a money market fund is practically nil. If you deposit your savings in a one-year GIC, you’ll be lucky to get 1.25%. With inflation running at about 3% so far this year, you are losing close to 2% in purchasing power each year. That’s a high price to pay for safety.

What about government bonds? The benchmark 10-year Government of Canada bond yield as of early November was 2.15%. Again, with inflation at about 3%, your net annual purchasing power loss is almost a full percentage point. And that doesn’t include fund fees.

These low yields might be a fair price if they came with peace of mind. They don’t. The important thing to remember with bonds is that your long-term return is mostly determined by the prevailing yield at the time of buying. Yes, you may have temporary capital gains if yields decline, or capital losses if they rise. However, those gains or losses disappear as you approach maturity. The major risk with bonds today is that if inflation stays high or rises further, you will be stuck with negative real returns.

There is one investment that gives you the best of both worlds: safety and inflation protection. It’s called a real-return bond (RRB), or inflation-protected bond.

Before I elaborate, let me explain how RRBs work. Traditional bonds have a “coupon,” which is the annual interest rate you receive on the principal. If the bond’s principal is $100 and the coupon is 1%, you’ll receive $1 in interest every year. (More properly, you’ll receive 0.5%, or 50 cents, every six months.) When the bond matures, you get your $100 returned to you.

With RRBs, the coupon always stays the same, but the principal gets adjusted every six months based on the rate of inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index. For example, if you invest $100 in an RRB and inflation is 2% during the period, the principal grows to $102. Your semiannual interest payment is based on that adjusted amount: you’d receive a payment of 0.5% of $102, or 51 cents. That goes on until the bond matures, at which point you receive the inflation-adjusted principal.

To me, RRBs are a plausible alternative for investors who want the safety of bonds combined with inflation protection. Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Today, the average yield on Canadian RRBs is 0.85% or so, excluding the inflation adjustment. In other words, 0.85% is your expected real return after inflation, but before management fees. Problem is, the cheapest RRB fund in Canada carries a 0.29% annual fee. So after paying fees, your real return on a bond held to maturity in this fund can’t exceed a paltry 0.56% per year.

That’s not all. The shortest RRB maturity available in today’s market is 10 years, and the average term to maturity of your typical fund is 20 years. Thus, by investing in one you will have condemned part of your portfolio to mediocrity for 20 years or so.

For those reasons, most analysts and advisors have stopped recommending RRBs to their clients. Their argument is simple. Not only is the return mediocre, but the risk, in their view, is high. Over the past 10 years or so, the yield on RRBs has gradually dropped from 4% to 0.85%. If yields revert back to the historical mean, capital losses could be significant. By significant, I mean that each 1% increase in RRB yields would reduce your fund’s market value by 16%.

Okay, that’s the downside. Stay with me though, because there’s an upside too. I personally am willing to live with the risk inherent in RBBs for several reasons.

First, an inflation-safe bond with mediocre returns is better than one exposed to inflation risk. Every investor needs some bonds in his or her portfolio, and I’d rather have the former.

Second, RRBs have an inherent stability mechanism and are therefore not as risky as people fear. The probability of RRB yields rising again is very low in the foreseeable future. Remember that bond yields rise for two reasons: when inflation expectations rise, or when the credit risk of the issuer worsens. With RRBs, the inflation adjustment takes care of the former. As for credit risk, RRBs are primarily issued by the federal (and to a much lesser extent, provincial) governments, all with good credit standing.

Third, bond yields are subject to the laws of supply and demand. Here is the key point: RRB supply is scarce, and when supply is short of demand, prices remain high (and yields remain low). Currently, RRBs represent no more than 5% of the total supply of government bonds. The Canadian government projects this to increase to 10%, but I still believe supply will remain tight.

The fact is, governments have a disincentive to issue RRBs unless they believe future inflation will stay very low. And barring a European-induced financial meltdown, global inflation is here to stay. While they won’t admit it, governments like this combination of low interest rates and moderate inflation because it lightens their debt burden significantly. If you’re paying 2% interest on your bonds and inflation is 3%, your real cost of borrowing cost is negative. If governments can borrow today at negative cost, why would they issue RRBs that close that gap and make borrowing more expensive?

With all of this in mind, putting some of your portfolio in an RRB fund is not a bad idea. But don’t go for the kill. The risk of higher yields—and therefore falling prices—cannot be completely ruled out. More importantly, don’t put in any money that you may need in the next five years. RRBs have very long maturities, and rising interest rates may force you to sell the bonds at a loss.

How much should one invest in RRBs versus regular bonds? Before you decide, understand that RRBs have a built-in inflation expectation. As I mentioned earlier, RRBs yield about 0.85% today, while regular government bonds with comparable maturities yield roughly 2.9%. The difference between those two yields (just over 2%) is what the market expects inflation to be. How much you allocate to RRBs and regular bonds depends on whether you agree with the market. If you expect inflation to be more than 2%, add more RRBs. If you expect inflation will be lower than that, you may want to favour traditional bonds. A balanced approach would include equal amounts of each.

Note that RRBs are not suitable for retired investors who rely on capital withdrawals to supplement their income. The income RRBs spin off is not that rich to start with, because the inflation adjustment is added to the principal, not paid out in cash. RRBs are most suitable for middle-aged investors who are saving for retirement and want to ensure their fixed-income investments keep pace with long-term inflation.

Click image to enlarge

During periods of market turmoil, most investors look for a safe haven. Unfortunately, some of today’s perceived havens can be more exposed than a beach resort in a hurricane.

Let’s start with cash. Today, the net return on a money market fund is practically nil. If you deposit your savings in a one-year GIC, you’ll be lucky to get 1.25%. With inflation running at about 3% so far this year, you are losing close to 2% in purchasing power each year. That’s a high price to pay for safety.

What about government bonds? The benchmark 10-year Government of Canada bond yield as of early November was 2.15%. Again, with inflation at about 3%, your net annual purchasing power loss is almost a full percentage point. And that doesn’t include fund fees.

These low yields might be a fair price if they came with peace of mind. They don’t. The important thing to remember with bonds is that your long-term return is mostly determined by the prevailing yield at the time of buying. Yes, you may have temporary capital gains if yields decline, or capital losses if they rise. However, those gains or losses disappear as you approach maturity. The major risk with bonds today is that if inflation stays high or rises further, you will be stuck with negative real returns.

There is one investment that gives you the best of both worlds: safety and inflation protection. It’s called a real-return bond (RRB), or inflation-protected bond.

Before I elaborate, let me explain how RRBs work. Traditional bonds have a “coupon,” which is the annual interest rate you receive on the principal. If the bond’s principal is $100 and the coupon is 1%, you’ll receive $1 in interest every year. (More properly, you’ll receive 0.5%, or 50 cents, every six months.) When the bond matures, you get your $100 returned to you.

With RRBs, the coupon always stays the same, but the principal gets adjusted every six months based on the rate of inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index. For example, if you invest $100 in an RRB and inflation is 2% during the period, the principal grows to $102. Your semiannual interest payment is based on that adjusted amount: you’d receive a payment of 0.5% of $102, or 51 cents. That goes on until the bond matures, at which point you receive the inflation-adjusted principal.

To me, RRBs are a plausible alternative for investors who want the safety of bonds combined with inflation protection. Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Today, the average yield on Canadian RRBs is 0.85% or so, excluding the inflation adjustment. In other words, 0.85% is your expected real return after inflation, but before management fees. Problem is, the cheapest RRB fund in Canada carries a 0.29% annual fee. So after paying fees, your real return on a bond held to maturity in this fund can’t exceed a paltry 0.56% per year.

That’s not all. The shortest RRB maturity available in today’s market is 10 years, and the average term to maturity of your typical fund is 20 years. Thus, by investing in one you will have condemned part of your portfolio to mediocrity for 20 years or so.

For those reasons, most analysts and advisors have stopped recommending RRBs to their clients. Their argument is simple. Not only is the return mediocre, but the risk, in their view, is high. Over the past 10 years or so, the yield on RRBs has gradually dropped from 4% to 0.85%. If yields revert back to the historical mean, capital losses could be significant. By significant, I mean that each 1% increase in RRB yields would reduce your fund’s market value by 16%.

Okay, that’s the downside. Stay with me though, because there’s an upside too. I personally am willing to live with the risk inherent in RBBs for several reasons.

First, an inflation-safe bond with mediocre returns is better than one exposed to inflation risk. Every investor needs some bonds in his or her portfolio, and I’d rather have the former.

Second, RRBs have an inherent stability mechanism and are therefore not as risky as people fear. The probability of RRB yields rising again is very low in the foreseeable future. Remember that bond yields rise for two reasons: when inflation expectations rise, or when the credit risk of the issuer worsens. With RRBs, the inflation adjustment takes care of the former. As for credit risk, RRBs are primarily issued by the federal (and to a much lesser extent, provincial) governments, all with good credit standing.

Third, bond yields are subject to the laws of supply and demand. Here is the key point: RRB supply is scarce, and when supply is short of demand, prices remain high (and yields remain low). Currently, RRBs represent no more than 5% of the total supply of government bonds. The Canadian government projects this to increase to 10%, but I still believe supply will remain tight.

The fact is, governments have a disincentive to issue RRBs unless they believe future inflation will stay very low. And barring a European-induced financial meltdown, global inflation is here to stay. While they won’t admit it, governments like this combination of low interest rates and moderate inflation because it lightens their debt burden significantly. If you’re paying 2% interest on your bonds and inflation is 3%, your real cost of borrowing cost is negative. If governments can borrow today at negative cost, why would they issue RRBs that close that gap and make borrowing more expensive?

With all of this in mind, putting some of your portfolio in an RRB fund is not a bad idea. But don’t go for the kill. The risk of higher yields—and therefore falling prices—cannot be completely ruled out. More importantly, don’t put in any money that you may need in the next five years. RRBs have very long maturities, and rising interest rates may force you to sell the bonds at a loss.

How much should one invest in RRBs versus regular bonds? Before you decide, understand that RRBs have a built-in inflation expectation. As I mentioned earlier, RRBs yield about 0.85% today, while regular government bonds with comparable maturities yield roughly 2.9%. The difference between those two yields (just over 2%) is what the market expects inflation to be. How much you allocate to RRBs and regular bonds depends on whether you agree with the market. If you expect inflation to be more than 2%, add more RRBs. If you expect inflation will be lower than that, you may want to favour traditional bonds. A balanced approach would include equal amounts of each.

Note that RRBs are not suitable for retired investors who rely on capital withdrawals to supplement their income. The income RRBs spin off is not that rich to start with, because the inflation adjustment is added to the principal, not paid out in cash. RRBs are most suitable for middle-aged investors who are saving for retirement and want to ensure their fixed-income investments keep pace with long-term inflation.

Click image to enlarge

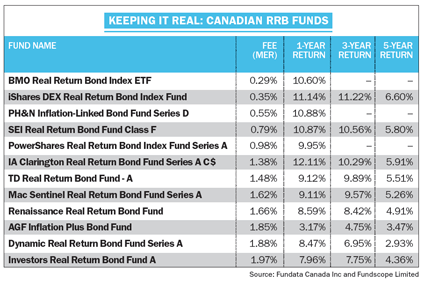

The “Keeping it real” chart lists RRB funds available to Canadian investors. As you can see, most of them are way too expensive. To begin with, there is no value added from active management, because all the fund managers have only a handful of bond issues to choose from. Therefore, the underlying portfolios in these funds are nearly identical. The best choice, therefore, is one of the less expensive exchange-traded funds, such as the BMO or iShares offering.

Both ETFs have very similar portfolios, with an average maturity of 20 years or so. The BMO ETF is entirely composed of federal government bonds, whereas the iShares ETF has a small component of provincial bonds with a slightly higher yield. I expect the two funds to deliver very similar returns over the long term. For the first half of 2011, both have reported a nominal annual income of 2%, made up of coupon payments with the inflation adjustment. I expect that to improve slightly to 2.5% or so in the second half due to higher inflation.

You’ll notice that the total returns on real-return bonds (that is, interest payments plus price increases) have been extremely good in recent years. But please do not be fooled. This is history that is not likely to repeat itself any time soon. As RRB yields kept dropping, bond prices climbed up. But yields have now reached very low levels and have limited room to drop further, unless people decide to start lending to the government for free. Therefore, the potential for any capital gains is much lower. You do not buy an RRB fund in order to make big bucks, but rather to protect your wealth from inflation while earning a small income.

The “Keeping it real” chart lists RRB funds available to Canadian investors. As you can see, most of them are way too expensive. To begin with, there is no value added from active management, because all the fund managers have only a handful of bond issues to choose from. Therefore, the underlying portfolios in these funds are nearly identical. The best choice, therefore, is one of the less expensive exchange-traded funds, such as the BMO or iShares offering.

Both ETFs have very similar portfolios, with an average maturity of 20 years or so. The BMO ETF is entirely composed of federal government bonds, whereas the iShares ETF has a small component of provincial bonds with a slightly higher yield. I expect the two funds to deliver very similar returns over the long term. For the first half of 2011, both have reported a nominal annual income of 2%, made up of coupon payments with the inflation adjustment. I expect that to improve slightly to 2.5% or so in the second half due to higher inflation.

You’ll notice that the total returns on real-return bonds (that is, interest payments plus price increases) have been extremely good in recent years. But please do not be fooled. This is history that is not likely to repeat itself any time soon. As RRB yields kept dropping, bond prices climbed up. But yields have now reached very low levels and have limited room to drop further, unless people decide to start lending to the government for free. Therefore, the potential for any capital gains is much lower. You do not buy an RRB fund in order to make big bucks, but rather to protect your wealth from inflation while earning a small income.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email