The crunch years: Where the money goes

What one man learned after tracking his expenses for 12 years

Advertisement

What one man learned after tracking his expenses for 12 years

I don’t want to overstate this plight. It’s hardly the stuff of Dickens; I’m not aware of any shantytowns in this country teeming with formerly upper middle-class families driven into poverty by the birth of their latest child. But the typical household spending pattern resembles a mountain, and people in their 30s and 40s are near the summit. “Young families will often transition from a relatively carefree financial existence to 10 or 20 years of having no room to maneuver at all,” says Malcolm Hamilton, a retired actuary and senior fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute. “If you have two children, the worst of it comes just after the birth of the second child.”

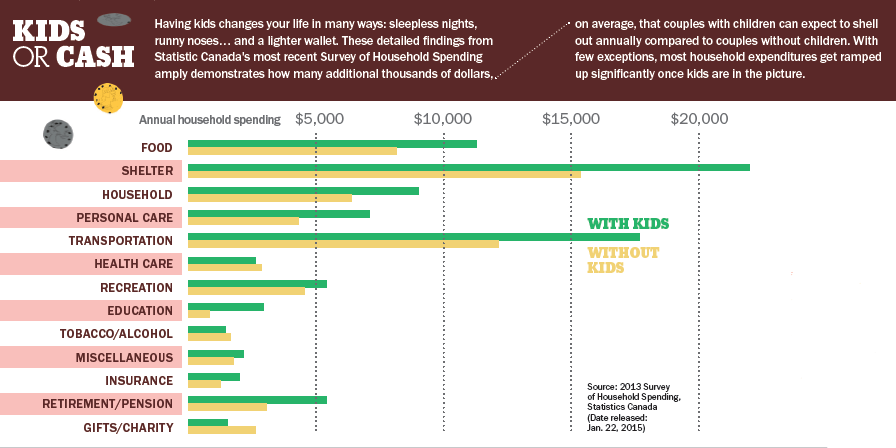

Statistics Canada’s latest data bear this out. The Survey of Household Spending, released in January, shows that in 2013 the average Canadian household spent just over $79,000. Of that, $59,000 went to goods and services. The rest went to income taxes, pension contributions, insurance premiums and cash gifts. That’s just a national average, and there’s considerable variation by household type, age and income level.

It turns out that the average senior (aged 65 or older), living alone, spent just $29,000 on goods and services. The reasons are not difficult to surmise: seniors are likely to own their home, and child-rearing costs (from diapers to university) are a distant memory. For couples with children, that spending was nearly $82,000—the highest of any household type. Unsurprisingly, younger families also carry higher debt relative to their incomes than their older counterparts, and so are more likely to be financially strained. Remember this next time you hear someone complain about how tough seniors have it.

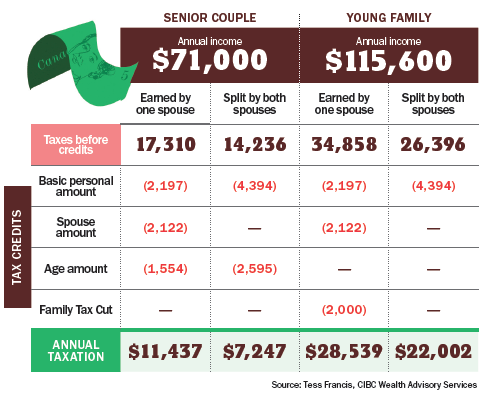

The authors of the Income Tax Act don’t give a damn, though. If you track your spending like I do, you’ll get a vivid reminder of how expensive it is to be Canadian. For those in the CRA’s higher tax brackets, income tax and government payroll deductions represent a huge chunk of total spending. Hamilton argues the government confuses income with standard of living, and therefore has created a tax system that clobbers many young families during the most expensive period of their lives, while providing unnecessary relief for the elderly, whose peak spending years are a distant memory. “The government will tax a family of four earning $100,000 much more heavily than two seniors with $70,000 of income,” says Hamilton. “That’s ass-backwards. It makes the situation that much worse.”

I don’t want to overstate this plight. It’s hardly the stuff of Dickens; I’m not aware of any shantytowns in this country teeming with formerly upper middle-class families driven into poverty by the birth of their latest child. But the typical household spending pattern resembles a mountain, and people in their 30s and 40s are near the summit. “Young families will often transition from a relatively carefree financial existence to 10 or 20 years of having no room to maneuver at all,” says Malcolm Hamilton, a retired actuary and senior fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute. “If you have two children, the worst of it comes just after the birth of the second child.”

Statistics Canada’s latest data bear this out. The Survey of Household Spending, released in January, shows that in 2013 the average Canadian household spent just over $79,000. Of that, $59,000 went to goods and services. The rest went to income taxes, pension contributions, insurance premiums and cash gifts. That’s just a national average, and there’s considerable variation by household type, age and income level.

It turns out that the average senior (aged 65 or older), living alone, spent just $29,000 on goods and services. The reasons are not difficult to surmise: seniors are likely to own their home, and child-rearing costs (from diapers to university) are a distant memory. For couples with children, that spending was nearly $82,000—the highest of any household type. Unsurprisingly, younger families also carry higher debt relative to their incomes than their older counterparts, and so are more likely to be financially strained. Remember this next time you hear someone complain about how tough seniors have it.

The authors of the Income Tax Act don’t give a damn, though. If you track your spending like I do, you’ll get a vivid reminder of how expensive it is to be Canadian. For those in the CRA’s higher tax brackets, income tax and government payroll deductions represent a huge chunk of total spending. Hamilton argues the government confuses income with standard of living, and therefore has created a tax system that clobbers many young families during the most expensive period of their lives, while providing unnecessary relief for the elderly, whose peak spending years are a distant memory. “The government will tax a family of four earning $100,000 much more heavily than two seniors with $70,000 of income,” says Hamilton. “That’s ass-backwards. It makes the situation that much worse.”

Then there’s the cost of shelter. Homeowners spent an average of nearly $18,700 on mortgage payments, repairs and maintenance, utilities and property taxes in 2013, representing more than 27% of total household spending. The picture is likely far bleaker if you just bought a detached home in downtown Vancouver or Toronto and took on a huge mortgage. Homes in these and other cities are now so pricey that new homebuyers are stretched to their limit. When I talk to young people who have just bought a house—even when they have a good income and saved diligently for a down payment—they sometimes confess that if they lost their job they’d run into trouble in a matter of a few months.

The best financial decision I ever made was waging guerilla warfare on my mortgage during years when our discretionary income was higher. Few financial events brought me greater satisfaction than terminating that mortgage early. I credit personal accounting software with helping me make that happen: I used it to marshal all available resources to maximize pre-payments. Watching debt charts and graphs trend downward kept me motivated, and the payoff was a more forgiving monthly budget once the war was won. Consider this: Households with a mortgaged home spend an average of $23,700 a year on shelter. Without a mortgage, that number drops to $9,600. Aggressive prepayments are not easy (or even possible) for many households. But I’ll say this: If you’re fortunate enough to enjoy some flush years in your 20s and 30s, don’t squander them.

Child care is the other financial scourge of dual-income parents, as well as many lone-parent and stepfamilies. A little less than half of parents with children 14 or younger used some form of child care in 2011 (the most recent year for which stats are available), but spending here is all over the map. It varies considerably by age; children aged two to four are most likely to be in daycare, and since it’s often all-day, five times a week, costs here can be through the roof. It also varies with where you live. According to Statistics Canada, the median monthly cost of full-time child care ranged from $152 in Quebec—home to Canada’s only subsidized, universal child care system—to $677 in Ontario.

Tracking your spending: Tips on how to get started »

Both figures seem like unattainable bargains to me. With one child attending daycare and another enrolled in an after-school program, I spent more than $17,000 on child care last year. That’s despite looking after my daughter personally two days a week and working weekends instead. Most working parents I meet have similar stories, and this is one service most are loath to leave to the lowest bidder. Words like “budget” and “discount” work well for car rental agencies. Somehow, Discount Child Care doesn’t have the same ring.

Again, I’m not complaining. The scents and sounds daycare workers are subjected to daily remind me of the CIA’s coercive interrogation methods. It’s difficult to avoid this cost if both parents remain in the workforce, but that’s a choice: many families get by with little or no daycare costs. In truth, many seemingly unavoidable expenses associated with the mid-life crunch simply reflect lifestyle decisions that are, in fact, discretionary. A few years ago, MoneySense calculated the average annual cost of raising a child at more than $12,000. The Fraser Institute responded with a withering paper arguing healthy children can be raised for just $3,000 and $4,500 a year. “Parents successfully raise children at all income levels,” its author, Christopher Sarlo, pointed out. Both figures are plausible; each is the product of different choices and circumstances.

Transportation is another budget-buster. My family comes in well below the average of nearly $18,000 among Canadian couples with children, and I attribute this to two decisions. The first was resisting the temptation to buy a second car. For many, a car is almost a prerequisite for participating in the workforce. For me, doing without is feasible—Toronto’s subways, buses and streetcars serve my needs fairly well. I’ve supplemented them with cycling and walking, and using the family car on those rare occasions when it’s available.

I’ve also contained my costs by buying only used vehicles and driving them into the ground. My data reveals that owning a single, modest vehicle costs my family an average of about $6,500 a year. That includes fuel, insurance, maintenance, registration, parking and depreciation. Not doubling that cost by owning two vehicles has been well worth any inconvenience. Every once in a while I see a properly quick roadster and briefly consider having a midlife crisis, but so far I’ve managed to restrain myself. Good thing, too. According to my projections, I can’t afford one until age 53.

Then there’s the cost of shelter. Homeowners spent an average of nearly $18,700 on mortgage payments, repairs and maintenance, utilities and property taxes in 2013, representing more than 27% of total household spending. The picture is likely far bleaker if you just bought a detached home in downtown Vancouver or Toronto and took on a huge mortgage. Homes in these and other cities are now so pricey that new homebuyers are stretched to their limit. When I talk to young people who have just bought a house—even when they have a good income and saved diligently for a down payment—they sometimes confess that if they lost their job they’d run into trouble in a matter of a few months.

The best financial decision I ever made was waging guerilla warfare on my mortgage during years when our discretionary income was higher. Few financial events brought me greater satisfaction than terminating that mortgage early. I credit personal accounting software with helping me make that happen: I used it to marshal all available resources to maximize pre-payments. Watching debt charts and graphs trend downward kept me motivated, and the payoff was a more forgiving monthly budget once the war was won. Consider this: Households with a mortgaged home spend an average of $23,700 a year on shelter. Without a mortgage, that number drops to $9,600. Aggressive prepayments are not easy (or even possible) for many households. But I’ll say this: If you’re fortunate enough to enjoy some flush years in your 20s and 30s, don’t squander them.

Child care is the other financial scourge of dual-income parents, as well as many lone-parent and stepfamilies. A little less than half of parents with children 14 or younger used some form of child care in 2011 (the most recent year for which stats are available), but spending here is all over the map. It varies considerably by age; children aged two to four are most likely to be in daycare, and since it’s often all-day, five times a week, costs here can be through the roof. It also varies with where you live. According to Statistics Canada, the median monthly cost of full-time child care ranged from $152 in Quebec—home to Canada’s only subsidized, universal child care system—to $677 in Ontario.

Tracking your spending: Tips on how to get started »

Both figures seem like unattainable bargains to me. With one child attending daycare and another enrolled in an after-school program, I spent more than $17,000 on child care last year. That’s despite looking after my daughter personally two days a week and working weekends instead. Most working parents I meet have similar stories, and this is one service most are loath to leave to the lowest bidder. Words like “budget” and “discount” work well for car rental agencies. Somehow, Discount Child Care doesn’t have the same ring.

Again, I’m not complaining. The scents and sounds daycare workers are subjected to daily remind me of the CIA’s coercive interrogation methods. It’s difficult to avoid this cost if both parents remain in the workforce, but that’s a choice: many families get by with little or no daycare costs. In truth, many seemingly unavoidable expenses associated with the mid-life crunch simply reflect lifestyle decisions that are, in fact, discretionary. A few years ago, MoneySense calculated the average annual cost of raising a child at more than $12,000. The Fraser Institute responded with a withering paper arguing healthy children can be raised for just $3,000 and $4,500 a year. “Parents successfully raise children at all income levels,” its author, Christopher Sarlo, pointed out. Both figures are plausible; each is the product of different choices and circumstances.

Transportation is another budget-buster. My family comes in well below the average of nearly $18,000 among Canadian couples with children, and I attribute this to two decisions. The first was resisting the temptation to buy a second car. For many, a car is almost a prerequisite for participating in the workforce. For me, doing without is feasible—Toronto’s subways, buses and streetcars serve my needs fairly well. I’ve supplemented them with cycling and walking, and using the family car on those rare occasions when it’s available.

I’ve also contained my costs by buying only used vehicles and driving them into the ground. My data reveals that owning a single, modest vehicle costs my family an average of about $6,500 a year. That includes fuel, insurance, maintenance, registration, parking and depreciation. Not doubling that cost by owning two vehicles has been well worth any inconvenience. Every once in a while I see a properly quick roadster and briefly consider having a midlife crisis, but so far I’ve managed to restrain myself. Good thing, too. According to my projections, I can’t afford one until age 53. I wish I could profess monastic restraint in all categories, but the data reveal otherwise. My spending on food and other staples, for instance, is above average even among families with children. By my calculations, our grocery bills are up nearly 40% from the years before children. (I include diapers in this category, which fortunately we don’t need to buy anymore.) But I can’t blame it all on the little tykes: my weakness for red meat and pathological dislike for vegetables almost certainly contributes.

It’s often said that you stop dining out once you have children, and my numbers concur. There’s no local pub where everybody knows my name. Not only that, but a host of other small expenses fall away: movies (in theatres), concerts and sporting events. (I’ve spent only $34 on sporting events in the last dozen years—and all of that at Chicago’s Wrigley Field eight years ago.) Another virtuous trend is that my appliances, furniture and home maintenance costs fell off sharply after I’d owned my home for five years.

Right now you’re probably thinking that my strange habit of tracking expenses sounds pretty off-putting. Dwelling on every last opportunity to save money is a good way to sour the flavour of life, you say, and I agree. But that’s not the point. It’s not really about the small stuff: the lattes are not the worst culprit. My advice to those feeling the crunch is this: be tough on yourself when making big decisions.

You’ll be living with the financial fallout from buying a bigger house or newer car for years to come, so resist the temptation to indulge in luxury. Revisit recurring costs like auto insurance and cellphones to explore whether there are new opportunities to lower or eliminate them. And whether you’re tracking or not, sit down every two years and ask yourself which expenses really have a positive impact on you and your family, and which ones you can do without.

There are plenty of other challenges once you’ve decided to track your finances, and most of them boil down to the time and effort involved. If you’ve decided to start tracking, you’ll need the right personal accounting software (see sidebar). Purveyors of these programs emphasize that their products are quick and easy to use, but this is only partly true. I’ve found a handful that are powerful and well designed, with time-saving features such as the ability to download transactions from financial institutions. That’s swell, but there are limits to automation. Downloaded transactions must still be properly categorized, for instance. My monthly credit card statement attempts to provide a “spend report” by automatically classifying items, but its categorizations are sweepingly broad and often inaccurate. (One of them is “groceries and retail.” To my mind, lumping bananas, two-by-fours and dishwashers together is unhelpful.) You’ll have the same problem if you let the accounting software categorize transactions for you. Unreliable data is worse than useless.

There’s also plenty of stuff that simply can’t be automated. At most brokerages, downloading stock and bond purchases, sales and dividends and importing them into your accounting software is tedious and error-prone. (Unless your wallet is some kind of Google prototype, it’s the same for your cash spending, which must be entered manually.) Doing this right involves at least an hour or two a month spent reviewing receipts and invoices and inputting reliable data. As with the laundry and dishes, you should keep on top of it. If you procrastinate a few weeks, you’ll have forgotten salient details of half the transactions you’ve participated in. More importantly, you need to set aside more time to review that data and decide which of your bad financial habits should be first to go.

Here’s the thing, though: using accounting software is worth the effort if you want a comprehensive view of your financial situation but find yourself juggling an assortment of accounts—chequing, savings, credit cards, RRSPs, TFSAs, non-registered accounts, and more. In my case, they’re spread across multiple financial institutions and it’s a chore to manage them using individual websites and monthly statements. Accounting software brings all that together to help me see what’s going on behind all the noise. It reminds me when to pay bills. It tells me how my investment portfolio—spread across four different accounts—performed last year. It breaks down your asset allocation by Canadian, U.S. and international stocks, bonds and more.

Yes, it’s a lot of work, but it can be particularly helpful if you’re arriving in mid-life and wondering where the devil is my money going? And how can I keep more of it? Once you’re armed with three or four months of data, you can start running your household finances as you would a business. It won’t make money appear out of thin air, but it can help you better manage what you have.

Tracking your finances also encourages you to think longer term. A year of lacklustre investment returns can have you second-guessing the strategy you carefully laid out years ago. But if you have several years’ worth of data, it’s easier to see whether you should make adjustments or stay the course. Gazing at the horizon is particularly helpful during the midlife crunch, a period when it can seem as if every financial wind imaginable blows directly in your face. Federal survey shows that household spending typically peaks when respondents are in their 40s—but just keep in mind that when you get older, you’ll have even more money and much more freedom in your budget. Most young families survive the mid-life crunch. So can yours.

I wish I could profess monastic restraint in all categories, but the data reveal otherwise. My spending on food and other staples, for instance, is above average even among families with children. By my calculations, our grocery bills are up nearly 40% from the years before children. (I include diapers in this category, which fortunately we don’t need to buy anymore.) But I can’t blame it all on the little tykes: my weakness for red meat and pathological dislike for vegetables almost certainly contributes.

It’s often said that you stop dining out once you have children, and my numbers concur. There’s no local pub where everybody knows my name. Not only that, but a host of other small expenses fall away: movies (in theatres), concerts and sporting events. (I’ve spent only $34 on sporting events in the last dozen years—and all of that at Chicago’s Wrigley Field eight years ago.) Another virtuous trend is that my appliances, furniture and home maintenance costs fell off sharply after I’d owned my home for five years.

Right now you’re probably thinking that my strange habit of tracking expenses sounds pretty off-putting. Dwelling on every last opportunity to save money is a good way to sour the flavour of life, you say, and I agree. But that’s not the point. It’s not really about the small stuff: the lattes are not the worst culprit. My advice to those feeling the crunch is this: be tough on yourself when making big decisions.

You’ll be living with the financial fallout from buying a bigger house or newer car for years to come, so resist the temptation to indulge in luxury. Revisit recurring costs like auto insurance and cellphones to explore whether there are new opportunities to lower or eliminate them. And whether you’re tracking or not, sit down every two years and ask yourself which expenses really have a positive impact on you and your family, and which ones you can do without.

There are plenty of other challenges once you’ve decided to track your finances, and most of them boil down to the time and effort involved. If you’ve decided to start tracking, you’ll need the right personal accounting software (see sidebar). Purveyors of these programs emphasize that their products are quick and easy to use, but this is only partly true. I’ve found a handful that are powerful and well designed, with time-saving features such as the ability to download transactions from financial institutions. That’s swell, but there are limits to automation. Downloaded transactions must still be properly categorized, for instance. My monthly credit card statement attempts to provide a “spend report” by automatically classifying items, but its categorizations are sweepingly broad and often inaccurate. (One of them is “groceries and retail.” To my mind, lumping bananas, two-by-fours and dishwashers together is unhelpful.) You’ll have the same problem if you let the accounting software categorize transactions for you. Unreliable data is worse than useless.

There’s also plenty of stuff that simply can’t be automated. At most brokerages, downloading stock and bond purchases, sales and dividends and importing them into your accounting software is tedious and error-prone. (Unless your wallet is some kind of Google prototype, it’s the same for your cash spending, which must be entered manually.) Doing this right involves at least an hour or two a month spent reviewing receipts and invoices and inputting reliable data. As with the laundry and dishes, you should keep on top of it. If you procrastinate a few weeks, you’ll have forgotten salient details of half the transactions you’ve participated in. More importantly, you need to set aside more time to review that data and decide which of your bad financial habits should be first to go.

Here’s the thing, though: using accounting software is worth the effort if you want a comprehensive view of your financial situation but find yourself juggling an assortment of accounts—chequing, savings, credit cards, RRSPs, TFSAs, non-registered accounts, and more. In my case, they’re spread across multiple financial institutions and it’s a chore to manage them using individual websites and monthly statements. Accounting software brings all that together to help me see what’s going on behind all the noise. It reminds me when to pay bills. It tells me how my investment portfolio—spread across four different accounts—performed last year. It breaks down your asset allocation by Canadian, U.S. and international stocks, bonds and more.

Yes, it’s a lot of work, but it can be particularly helpful if you’re arriving in mid-life and wondering where the devil is my money going? And how can I keep more of it? Once you’re armed with three or four months of data, you can start running your household finances as you would a business. It won’t make money appear out of thin air, but it can help you better manage what you have.

Tracking your finances also encourages you to think longer term. A year of lacklustre investment returns can have you second-guessing the strategy you carefully laid out years ago. But if you have several years’ worth of data, it’s easier to see whether you should make adjustments or stay the course. Gazing at the horizon is particularly helpful during the midlife crunch, a period when it can seem as if every financial wind imaginable blows directly in your face. Federal survey shows that household spending typically peaks when respondents are in their 40s—but just keep in mind that when you get older, you’ll have even more money and much more freedom in your budget. Most young families survive the mid-life crunch. So can yours.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email