A perfect fit

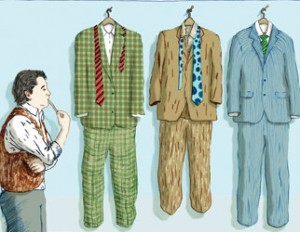

Want investment advice that makes you look like a million bucks? You have three options: adviser, broker or investment counsel. We’ll help you make the right choice.

Advertisement

Want investment advice that makes you look like a million bucks? You have three options: adviser, broker or investment counsel. We’ll help you make the right choice.

John and Linda Lee recently went looking for professional help with their investments. But instead of finding a professional they could trust, all the Toronto couple managed to find was a big headache. Lots of people out there were only too eager to sign them on as clients, but even though the Lees are seasoned investors (we’ve changed their names to protect their privacy), they quickly found themselves bewildered by all the different types of services on offer. They worried about making the wrong choice. “You have to be on your toes,” says John.

Fortunately, we can help. We’ll profile the three major types of investing professionals: mutual fund advisers, brokers, and private investment counselors (also known as portfolio managers). We’ll explain the products and services you get from each channel, and tell you the fees you can expect to pay. We’ll look at the strengths of each, and offer some words of warning about common mistakes to avoid.

For starters, we can tell you this: Whichever option you choose, an experienced, well-qualified professional doesn’t come cheap. You’ll pay anywhere from 1% to almost 3% of your assets each year, depending on experience, the financial institution, your choice of products, and the size of your account.

If you have the knowledge and confidence to invest on your own, you can save yourself a bundle. However, we also understand that many people want help. Even those who don’t seek help might want to at least consider it, as we are often overconfident about our investing abilities. As Warren MacKenzie, president of Weigh House Investor Services in Toronto, says: “Sometimes people who are doing it themselves should fire themselves.”

The investment professionals who follow are almost always offering some kind of “active” investing strategy, which means they’re trying to outperform the market, or earn market returns with lower risk. These pros earn their fees by helping you build a diversified portfolio, making the actual investment purchases, maintaining your asset allocation, and by providing broader financial advice. If you find a good adviser, it can be like finding the perfect suit. Not only will you look good, but you’ll feel comfortable and confident too. Pick a bad one though, and you’ll end up spending a lot of money on something you’d be better off without.

Mutual fund advisers

Perhaps the most common way to invest in mutual funds is through your bank. You can visit your local branch and work with a licensed mutual fund salesperson, who is likely a salaried employee. These professionals are less likely to have the in-depth financial designations you might find elsewhere — although some may be Certified Financial Planners (CFPs) or Personal Financial Planners (PFPs). But the banks have thorough procedures to guide their staff in making appropriate recommendations. This means you’ll probably get a cookie-cutter approach, and you’ll likely have access to a limited menu of the bank’s own products.

However, you should wind up with solid mutual funds that are a bit less costly than what you can expect from non-bank advisers. Banks also have a knack for making the process easy, including setting up automatic contributions to your funds.

If you invest in mutual funds through a bank branch, getting ongoing, high-quality advice about managing your portfolio may not be so easy. As an alternative, some banks offer mutual fund “wraps” (also known as “funds of funds”), which combine individual mutual funds into a portfolio that gets periodically rebalanced so it keeps a consistent asset mix. An example: the TD Comfort Balanced Portfolio places 55% in a fixed-income fund and divides the other 45% among four Canadian and global equity funds, all for a combined fee of less than 2%.

You can also work with an independent adviser who is affiliated with a non-bank mutual fund dealer, including large institutions like Assante Wealth Management, as well as smaller, lesser-known firms. If you go this route, you’ll probably find a commission-based adviser who offers a wider array of choices, and is more likely to have a designation like the CFP. Independent advisers often combine mutual fund sales with financial planning, which is usually included in their fees. Many are also licensed to sell other products, like insurance and annuities.

How they get paid

No matter what they tell you, all advisers are paid — and they’re often paid very well. Outside of the salaried bank advisers, most receive a share of the fees charged by the funds they sell to you. Mutual funds sold in Canada tend to have high fees: for a balanced portfolio of stock and bond mutual funds, you’ll typically pay a bit less than 2% a year through a bank branch, or a bit more than 2% through an independent mutual fund adviser. Fees are higher for equities than they are for bonds.

These fees are included in the fund’s management expense ratio (MER), which should be disclosed on the fund’s fact sheet. (If it’s not, look for it in the prospectus.) Part of the MER goes to the investment firm that sponsors the fund, while the rest goes to the adviser and the dealer as “trailer fees.” These trailer fees are about 1% a year for equity funds and 0.5% for bond funds.

Many advisers sell mutual funds with deferred sales charges (also called DSCs, or “back-end loads”). With these funds, you’ll not only pay the annual MER, but you’ll get dinged with a hefty charge if you sell within a set period, usually six or seven years. This charge typically starts at 5% or 6% and tapers off until the lock-in period is complete. Many advisers like DSC funds because they get some of their fees from the mutual fund sponsor right away. But back-end loads are controversial, and some institutions and advisers refuse to sell them at all.

A few advisers try to tack on a “front-end load,” or up-front sales commission, when you purchase a mutual fund, although this is becoming increasingly rare.

A small number of mutual fund advisers charge you their fee directly instead of being paid through commission. In that case, they should sell you “F-class” mutual funds which don’t pay trailer fees and thus have much lower MERs. Your overall cost may be similar, but at least you’ll know that the adviser is selecting funds based on your best interest, not the ones that pay higher trailer fees.

Who they’re right for

“For very small investors, mutual funds can be great products,” says Gordon Stockman, a fee-only financial planner with Efficient Wealth Management Inc. in Mississauga, Ont. Even if you have as little as $1,000, you can get good diversification and professional management.

If you’re looking for the personal touch and broad financial advice, you’re probably best off looking for a non-bank independent mutual fund adviser. If you’re after easy access to good funds at a relatively low price, you’ll probably find what you’re looking for in a bank branch.

“Some of the banks serve small clients incredibly well by helping them set up automatic withdrawals from their paycheque, getting them into good mutual funds, and getting them started on accumulating some wealth,” says Tessa Wilmott, a financial services consultant with Market Logics Inc., a Toronto-based market research and consulting firm.

What to watch out for

The biggest problem with mutual fund advisers in Canada is excessive fees. If you’re investing $50,000, an adviser who provides you with a diversified portfolio and a wide range of services for 2% (or $1,000 per year) may be good value. “You get all of that at a high percentage cost, but a low dollar cost,” says Stockman. But the percentage doesn’t decline as your portfolio grows. “The problem is as the portfolio gets larger, the fees in dollar terms get very high. That’s my fundamental objection to mutual funds: people outgrow them.”

If you have $250,000 portfolio of mutual funds with an average MER of 2%, you’re paying $5,000 a year in fees. For that kind of money, many brokers can give you sophisticated advice and a broader range of financial products at a lower cost. While there is no fixed cutoff point, consider a broker when your portfolio grows to about $250,000.

MERs on individual mutual funds vary widely, and higher fees do not generally mean better performance. In fact, the opposite is often true. For that reason, you should avoid paying more than 2.5% for an equity mutual fund or 1.5% for a Canadian bond fund, since there are many good options at that fee level or lower. While mutual fund wraps offer convenience and professional management, some have large minimum investments (up to $50,000) and hefty fees of 2.5% a year or more. Shop around for versions with a more reasonable fee at around 2% or lower.

Be skeptical of DSCs: if your mutual fund turns out to be a lemon, you’ll be forced to choose between paying the hefty fee to dump it, or holding on to it for years. If your adviser insists on a front-end load, consider taking your business elsewhere.

You should also be aware that the quality of financial planning you get from mutual fund advisers varies widely. Some have years of training, but others are no more than commissioned salespeople just out of school. They can quote you a few sales pitches, but they only have a shallow understanding of the products they’re selling.

You also have to watch out for potential conflicts of interest. If you ask a commissioned adviser how much you need to retire, for example, he or she may quote you an extremely high figure to encourage you to invest more money. But if you do find a well-qualified adviser, ask lots of questions and make them work for their fees, Stockman says. “The biggest mistake made by small investors is not making the mutual fund rep work hard enough.”

Full service brokers

When you hear the term “broker,” you may think of a brash, fast-talking salesman who calls you up with hot stock tips. While that may have been accurate 30 years ago, it’s rare today. Most of today’s brokers are focused on managing all aspects of your wealth—in fact, they’re now more likely to call themselves “investment advisers,” and may not even use the term “broker” anymore.

Individual brokers typically work with large investment dealers, such as the brokerage arms of the banks, but they have a remarkable amount of independence. They’re usually free to choose from a wide range of products, not just those managed by their institution. In addition to selling mutual funds and GICs, brokers are also licensed to advise you on individual stocks, bonds and other securities, such as ETFs, which mutual fund reps are not permitted to do.

Brokers can also help you invest in pooled funds and segregated accounts. Pooled funds are essentially low-fee mutual funds with large minimums; segregated accounts are similar, except you own the securities directly, and sometimes you can tailor the contents to your needs. (Don’t confuse them with “segregated funds,” which are products offered by insurance companies.) Some brokers are specially licensed to provide “discretionary portfolio management,” which means that they can buy and sell securities in your account without your explicit permission. Most, however, require you to approve each individual trade.

How they get paid

Nowadays brokers are increasingly likely to charge a fee based on a percentage of assets, and less likely to slap you with a commission when you buy or sell securities. “The brokerage industry is in the throes of reinventing itself,” says Scott Gibson, a financial planner and vice president of EES Financial Services Ltd., with offices in Montreal and Markham, Ont. After all, with online brokerages offering trades for as little as $5, investors no longer need a broker just to buy and sell stocks.

Unlike with a mutual fund adviser, if you’re paying on a percentage basis, you can negotiate lower fees as your nest egg grows. If you have $1 million or more, you’ll likely pay 1% to 1.5%; if you have less than $500,000, expect to pay closer to 2%. “Some old accounts up to $1 million still pay 2%, believe it or not,” says Stockman, who notes that rates have been gradually coming down.

If you pay by commission instead, you’re looking at a minimum of $150 to $175 per trade, says Gibson.

Which fee structure is better is hotly debated. If you’re a buy-and-hold investor, you’ll probably dole out less money by paying on a commission basis. On the other hand, paying a percentage of assets gives you the freedom to instruct your broker to make appropriate changes to the portfolio without worrying about the hefty trading commissions, while at the same time removing incentives for the broker to trade excessively.

If you buy mutual funds through a broker who charges an asset-based fee, he should sell you the low-MER “F-class” versions which don’t pay trailer fees. (If a fee-based broker sells you A- or B-class funds with trailer fees, you’re paying twice for the same advice.)

Brokers can often provide GIC rates that offer much better than you can get in a bank branch. But make sure your broker puts the GICs in a side account that is not subject to the overall fee for assets.

Who they’re right for

If you’re a very small investor, brokers may not want to take you on. But once you have several hundred thousand dollars to invest, they can offer a greater variety of investments and often at lower cost than a mutual fund salesperson.

Brokers can also give investors access to a range of sophisticated services. Consider Marilyn Trentos, a broker with RBC Dominion Securities (RBCDS) in Richmond Hill, Ont. She has her Canadian Investment Manager (CIM) designation and is licensed to provide discretionary portfolio management. She has an options license, so she can buy and sell those complex financial products. And she is licensed as a “private counselor” in the U.S., so she can provide investment assistance to snowbirds when they reside there. In addition, she draws on support from scores of expert analysts in RBCDS’s research department, as well as the firm’s specialists in financial planning, tax, and wills and estate planning, whose services are often available to clients without additional charge.

What to watch out for

The wide range of products and services brokers offer can also be a weakness. “A disadvantage of the broker channel is that they manage a large number of client accounts who all hold something different,” says Stockman. That makes it difficult for a broker to closely monitor each account. “To me, the problem with brokers is the diversity of their client base.”

So ensure that your broker is staying on top of your portfolio. Some, like Trentos, simplify the task by relying heavily on their firm’s “focus lists” of recommended stocks, which are backed up by credible research. “You can’t reinvent the wheel for each client,” says Trentos.

Investment counsel

Private investment counsel firms might be the best money management channel that you’ve never heard of. These companies give you attentive service from exceptionally qualified professionals who manage all aspects of your investments.

Rather than just advising you, investment counselors — also called portfolio managers — make the actual day-to-day decisions on what securities to buy and sell, which is known as discretionary portfolio management. (Some brokers are licensed to do this as well, but investment counselors usually manage money exclusively on this basis.) Of course, these investment choices are subject to your overall direction. When you first hire a portfolio manager, you’ll draw up a document called an Investment Policy Statement, which acts as a blueprint. They will typically invest your money in pooled funds, or in segregated accounts.

Discretionary portfolio managers must have either the well-regarded Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation, or the less-rigorous but still respected CIM. Investment counselors have a fiduciary duty to you, which means that they are professionally and legally bound to act in your best interest. That makes them fundamentally different from advisers in other channels, who are simply required to make sure an investment is “suitable.” Best of all, private investment counsel firms do all of this at very reasonable cost.

What’s the catch? Most portfolio managers require a minimum account size of at least $500,000, and many stipulate $1 million or more before they will take you on.

Private investment counsel is offered by divisions of the six major banks, by small boutique firms, and by institutional money managers who also handle pension funds. Bank-owned firms will typically provide other wealth management services (similar to those offered by bank-owned brokerages), whereas non-bank firms are more likely to just handle investments.

How they get paid

In keeping with their role as fiduciaries, investment counsel firms receive no commissions from investment products. They typically charge fees of 1% to 1.5% of assets per year, although you might pay less if you have an exceptionally large nest egg, or if most of your portfolio is in fixed income.

Who they’re right for

Clients of investment counselors are often wealthy professionals, business owners or retirees. For those who meet the minimum account size, many experts recommend this channel. “For a person with half a million dollars who doesn’t want to do it himself, this is the best way to do it,” says Warren MacKenzie of Weigh House.

What to watch out for

Investment counselors tend to offer a limited number of pooled funds and segregated account models (albeit well-managed ones). This approach may not be for you if you’re a hands-on investor who prefers to approve every trade, or if you want tap into a wider range of choices.

Private investment counsel firms tend to do little to promote themselves and shun advertising, so finding one isn’t easy. Visit the Portfolio Management Association of Canada’s web site, which provides information about each of its member firms, listed by minimum account size and locale. (Also see The real secret of the rich.)

In the end, choosing the right financial professional often comes down to your individual needs and personal tastes. Whichever path you choose, references from family, friends or other professionals will often point you in the right direction. If you have a large portfolio or very specific needs, consider hiring a financial planning firm to match you with the right adviser.

That’s what John and Linda Lee ended up doing. They originally invested with mutual funds, but as their savings started to grow they felt they weren’t getting the personal attention they deserved. “And the fees really drove me crazy,” says John, a general contractor who is hoping to retire in the next few years. “I couldn’t get into some funds without a front-end fee. I couldn’t get out of any of them without paying a back-end fee. No one did anything for me, and I just paid a lot of money.”

Next the Lees tried brokers, with mixed results. They had one they liked, but he retired and they moved to a broker who wasn’t meeting their needs. “He had an agenda of his own and he was very arrogant about pursuing it,” says John.

So with Weigh House Investor Services as a matchmaker, the Lees considered two new professionals with good reputations and reasonable fees. One was a private investment counselor, the other a broker who also provided discretionary portfolio management. That appealed to John. “I don’t want to be called three times a week, every time he makes a trade.”

The Lees selected the broker, and they believe the time and money they invested in the search was well worth it. They’re now working with a professional, with whom they’ve made a strong personal connection. But while they believe their investments are in good hands, they plan to stay closely involved. “It’s never a done deal,” says John. “You have to be educated to first pick a professional and then to follow up to make sure they’re doing a reasonable job. You can’t go, ‘That’s that, my financial future is taken care of,’ like the ads tell you. You’ve got to stay on top of it.”

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email