Surviving the crunch

How to face the biggest financial burdens—family costs and a mortgage—at the same time

Advertisement

How to face the biggest financial burdens—family costs and a mortgage—at the same time

Julie and Noel Bond seemed well on their way to realizing the Canadian dream when they moved east of Vancouver to the small community of Mission in 2014 so they could afford a three-bedroom house for their growing family. They now have two pre-school children and are expecting a baby in March.

While Julie plans to stay home to look after the kids for a year after the baby’s birth, the couple face a tricky financial dilemma over what to do after that. For Julie to return to her part-time $30,000-a-year teaching job would be pointless because her entire paycheque would be eaten up by child-care costs. But the $80,000 a year Noel earns as a railway worker isn’t enough by itself to cover the mortgage and other expenses if Julie stays home to look after the kids. Whether Julie, who is 36, returns to her old job or stays home, they expect ongoing expenses to exceed take-home pay by about $1,000 a month. That leaves Julie looking for solutions and wondering, “What will my family do?”

Julie and Noel Bond seemed well on their way to realizing the Canadian dream when they moved east of Vancouver to the small community of Mission in 2014 so they could afford a three-bedroom house for their growing family. They now have two pre-school children and are expecting a baby in March.

While Julie plans to stay home to look after the kids for a year after the baby’s birth, the couple face a tricky financial dilemma over what to do after that. For Julie to return to her part-time $30,000-a-year teaching job would be pointless because her entire paycheque would be eaten up by child-care costs. But the $80,000 a year Noel earns as a railway worker isn’t enough by itself to cover the mortgage and other expenses if Julie stays home to look after the kids. Whether Julie, who is 36, returns to her old job or stays home, they expect ongoing expenses to exceed take-home pay by about $1,000 a month. That leaves Julie looking for solutions and wondering, “What will my family do?”

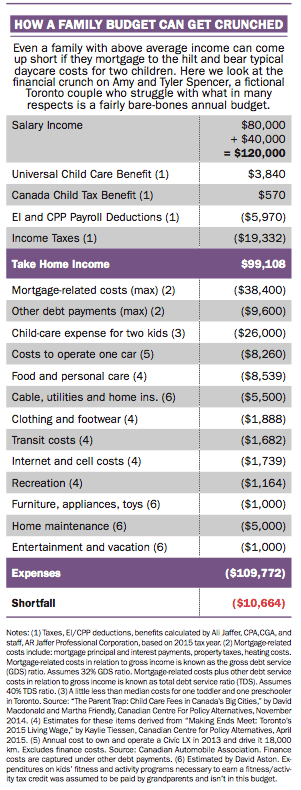

the help of chartered professional accountant Ali Jaffer and staff at AR Jaffer Professional Corporation to calculate taxes and benefits for 2015. The Spencers live in Toronto and earn a little bit more than the real-life Bonds. They have combined salaries of $120,000 (one spouse earns $80,000 and the other earns $40,000). They have taken on as big a mortgage as their financial institution will allow in order to buy the best house they can for their kids. They have two preschool-aged children in private daycare and pay $26,000 a year in fees, a typical amount in Toronto these days. We put together a fairly bare-bones budget for them and found they ended up with a shortfall of more than $10,000 a year.

That means you have to plan for the crunch years at the start. “You have to think through at the point you buy the house, how many children are you going to have, and how you are going to care for those children until they go to school, and how much is it going to cost?” says Hamilton. “If you wait until later to figure it out, you may have painted yourself into a corner.”

the help of chartered professional accountant Ali Jaffer and staff at AR Jaffer Professional Corporation to calculate taxes and benefits for 2015. The Spencers live in Toronto and earn a little bit more than the real-life Bonds. They have combined salaries of $120,000 (one spouse earns $80,000 and the other earns $40,000). They have taken on as big a mortgage as their financial institution will allow in order to buy the best house they can for their kids. They have two preschool-aged children in private daycare and pay $26,000 a year in fees, a typical amount in Toronto these days. We put together a fairly bare-bones budget for them and found they ended up with a shortfall of more than $10,000 a year.

That means you have to plan for the crunch years at the start. “You have to think through at the point you buy the house, how many children are you going to have, and how you are going to care for those children until they go to school, and how much is it going to cost?” says Hamilton. “If you wait until later to figure it out, you may have painted yourself into a corner.”

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email