Who’s to blame for high home prices?

Demographics, for one

Advertisement

Demographics, for one

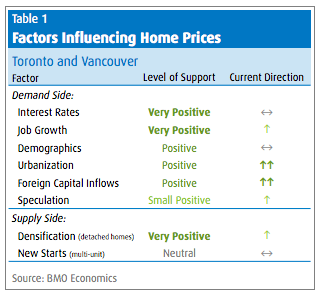

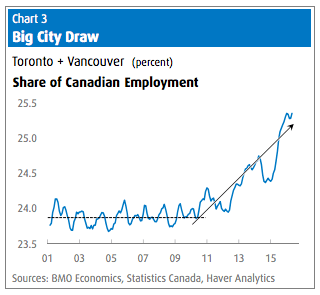

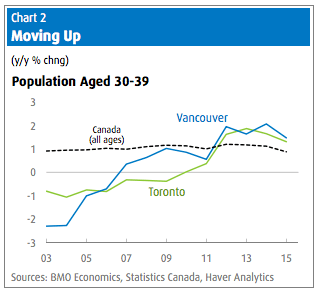

Canadian existing home sales slipped 2.8% in May (seasonally adjusted), leaving activity a still-firm 9.6% above year-ago levels and just down from a record high. Supply, however, remains extremely tight, with new listings falling 3.2% in the month, or 4.1% in the past year. That left the months’ supply of homes available on the market steady at 4.7, the lowest since January 2010 (i.e., when demand was surging out of the recession). That combination continues to push prices higher, especially in the country’s two hottest markets. The average Canadian transaction price was up 13.2% year-over-year in May, while the benchmark price rose 12.5%year-over-year, the strongest clip since 2007. But, as you are by now well aware, this is entirely a two-city story, with benchmark prices in Vancouver flaring 29.7%year-over-year in the month (including a nosebleed-inducing 37% year-over-year rise in detached homes), while Toronto prices are up 15% year-over-year.According to BMO Chief Economist, Douglas Porter, and Senior Economist, Robert Kavcic, there are a handful of factors that directly or indirectly impact real estate prices in Toronto and Vancouver. In an effort to appreciate how each factor impacts housing, Porter and Kavcic examined and rated each factor to assess the impact it had on Canada’s residential housing market. Yes, interest rates play a significant role, but as Porter and Kavcic point out in their report: “record low borrowing costs are the most obvious factor behind lofty home prices, [but] the fact that the surge in prices is so heavily concentrated in just two cities (and their environs) means that there are other important factors at play as well.” By assessing each factor, Porter and Kavcic developed an appreciation for which factor has had the most impact on Canada’s residential housing trends.

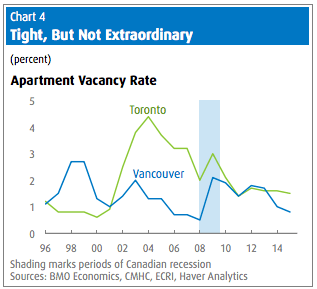

“We have supply issues,” Morneau said during the Canada Summit conference, held in Toronto Wednesday. “There’s 5.5 families for every single detached home in Vancouver. There’s 1.8 families across the country for every single detached home.”Suddenly, lack of supply is the No. 1 reason for high housing prices. But as Kavcic and Porter point out: “it was only a few short years ago that the single biggest supposed sign of Canada’s housing bubble was the “rampant overbuilding” in Toronto’s condo market.” Apparently, we can’t quite get the formula right. Overbuilding one year. Under-building the next. Too many condos. Not enough single-family detached homes. “The reality is that overall home building has been relatively healthy in the two big cities, and broadly in line with demographic demand—for example, vacancy rates have held relatively stable at fairly tight levels. Of course, there has been an imbalance between the new supply of condos and detached homes, but that would explain why relative home prices would shift, not why the whole structure of prices would ratchet higher,” write Porter and Kavcic. So that leads us to the issue of land restrictions and densification. “The composition of [the housing supply] is playing an increasing role in driving detached-home price gains. In a nutshell, while demand for single-detached homes has been rising at a brisk pace, supply of those homes has become almost irresponsive.” Turns out the number of detached homes in Vancouver has hardly budged in two decades, and in Toronto, the number of single detached units completed in 2015 was the lowest since 1979, according to the BMO report. While Vancouver can truly plead a land shortage, it’s Toronto’s push for densification—a push that dates back decades—that is the reason why we are witnessing the end of single-family homes being built on 50-foot lots in the city. So, what’s a policymaker to do? Realize that there is no one-stop, broadsword fix to this problem. But that doesn’t mean ignore the problem. More and more the option to impose a tax is looking good. Whether it’s a foreign buyer’s tax or a tax on capital gains above a certain threshold or a tax on flipped properties, or a combination of all three. At least if we de-incentivize parking money or making quick money with Canadian real estate then you can chase out most of the marginal buyers and leave the family-builders and homeowners to get on with building communities. Read more from Romana King at Home Owner on Facebook »

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email