How to avoid overspending at the grocery store

This dad shops with a list but doesn't have a grocery budget. Here are ways he can save

Advertisement

This dad shops with a list but doesn't have a grocery budget. Here are ways he can save

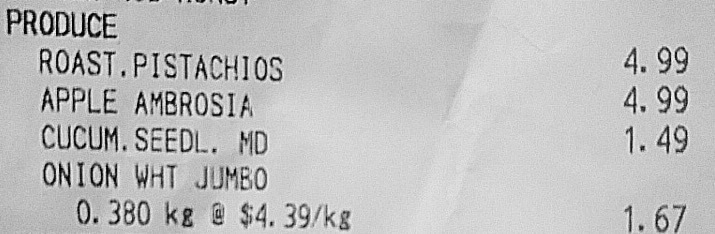

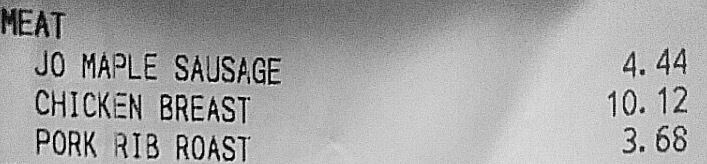

READ: How this Toronto nurse on a diet spent $150 at No Frills“For the most part 10 bucks here or 10 bucks there, it’s not going to affect me too much on a weekly basis,” he says. As a busy working dad, he’d rather go to a grocery store where he knows the layout and what’s in stock, so he can get in and out fast. “This weekend they’re coming to my house for five days, so I’ll go out tonight or tomorrow and do a big shop for the five days,” he says, “And I’ll pretty much write it out, each meal, what I’m getting them and what I’m going to cook for them, and it’s usually based on whatever is available to me at the market.” His strategy is to find food on sale or find inexpensive cuts of meat. “I’m really lucky that both of my kids eat well and eat a lot and eat a variety of food. I’m lucky that I can kind of experiment on them,” he says. Like many divorced parents, he doesn’t bother cooking much when he’s on his own. “When they’re not here, it’s usually leftovers from the five-day cycle, and you get a bit lazy and treat yourself out for dinner,” he says. The bill he’s given us is from a Metro trip when he doesn’t have his children visiting, which is why it only totals $47.25. Yet, there are still plenty of suggestions we have on easy ways to save:

RELATED: How a single mom spends $600 a month on groceriesIt’s not entirely his fault, since a grocery store is designed to make you spend money. “Grocery shopping, start to finish, is a cunningly orchestrated process. Every feature of the store—from floor plan and shelf layout to lighting, music, and ladies in aprons offering free sausages on sticks—is designed to lure us in, keep us there, and seduce us into spending money,” writes Rebecca Rupp in a 2015 National Geographic article on the sneaky psychology of supermarkets. The best way to avoid falling into the trap the grocery-store marketers have laid for us is to come in with a list and a plan. That way you can stay focused and avoid distractions. The worst thing you can do is enter a grocery store hungry, unsure about what you’re eating for the week ahead. Shoppers only have about 40 minutes where they’re being rationally selective, writes Rupp, after which point their brain switches to emotional decision making. It’s too overwhelming for your brain to make so many decisions on the spot — supermarkets contain about 44,000 different items —and you’re likely to end up with stuff you don’t need, at prices you don’t want to pay.

This post is part of Spend It Better, a personal finance collaboration between Chatelaine and MoneySense about how to get the most for your money. You can find out more right here.

This post is part of Spend It Better, a personal finance collaboration between Chatelaine and MoneySense about how to get the most for your money. You can find out more right here.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email