How retired parents can use the FHSA to help their adult children

Canada’s new first home savings account nicely complements earlier real estate programs. Retirees with grown adult children should take note when it launches early in April.

Advertisement

Canada’s new first home savings account nicely complements earlier real estate programs. Retirees with grown adult children should take note when it launches early in April.

If you’re a retiree or close to retiring, you probably have a paid-off principal residence, or should be close to having one.

However, many retirees—including me—have grown children struggling to get onto the first rung of the real estate ladder. Coming up with a down payment is still difficult. Home prices have fallen since interest rates started to rise in 2022, but mortgage affordability is still an issue for many young Canadians just starting out in their careers.

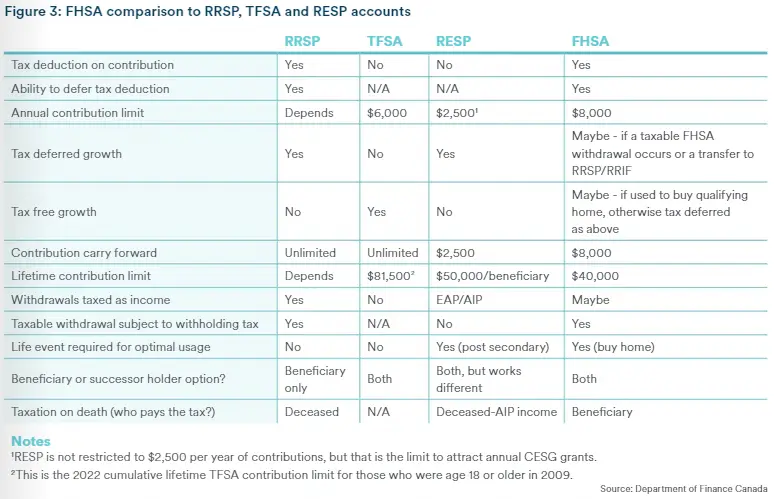

All of which makes the new first home savings account (FHSA) timely: Scheduled to debut on April 1, 2023, the FHSA is a much-talked about financial product right now. See some excellent blogger commentary on the topic, notably this one from Dale Roberts’ cutthecrapinvesting.com, and this summary from Mark Seed’s myownadvisor.ca. Both used a graphic from CFP/RFP Aaron Hector, a private wealth advisor at Calgary-based CWB Wealth. (TFSA room is $6,000 for 2022 and $6,500 for 2023.)

Before we get into the mechanics of how the FHSA works, know that this new program may also be of interest to parents who are retired and are wishing to diversify family investment assets further into real estate.

In my family’s case, apart from the paid-up principal residence our only exposure to real estate is through exchange-traded funds (ETFs) containing real estate investment trusts (REITs). REITs appeal to those Canadians wanting to avoid the hassle of being a landlord and managing properties and tenants. But if you want more direct exposure to residential real estate, expanding the family wealth from one principal residence to a second or third (or more) for the kids might be one way to do that.

Remember that one benefit of a principal residence is you can sell it down the road without capital gains tax, as you would with a second property, such as a vacation home or rental property.

Counting the FHSA, there are now three tax-efficient government programs that can be combined to help young soon-to-be home owners save up for a down payment.

The first created was the Home Buyer’s plan (HBP), launched in 1992, which lets first-time home owners withdraw up to $35,000 from their registered retirement savings plan (RRSP). It can also be used with the FHSA.

The second is the tax-free savings account (TFSA), launched in 2009. It’s not specifically designed for home ownership, but it can certainly be used for saving for real estate, or for other big financial goals. In the Chevreau household, we’ve always looked at TFSAs as a way to minimize taxes across the family unit. And, as we’ll see, the FHSA should work like a TFSA and RRSP in some ways.

Let’s assume one or more of your adult kids have decided to take the plunge into buying a principal residence, given the confluence of lower prices and this new program.

To qualify for the FHSA, you must be at least 18 years old, Canadian and be a first-time home buyer, but can only tap the FHSA once. You can contribute $8,000 each year, with a lifetime limit of $40,000. An immediate benefit is that contributions create a tax deduction, like an RRSP does. However, Roberts cautions, “unlike RRSPs, contributions made within the first 60 days of a given calendar year cannot be attributed to the previous tax year.”

On his blog, Mark Seed says an FHSA account can stay open for 15 years, or until the end of the year you turn 71, or until the end of the year following the year in which you make a qualifying withdrawal from an FHSA for the first home purchase—whichever comes first.

Seed addresses “the elephant in the room” that is: What happens if you open an FHSA account but ultimately don’t buy a home?

No problem, he writes. “Any savings not used to purchase a qualifying home could be transferred to an RRSP or RRIF (registered retirement income fund) on a non-taxable transfer basis, subject to applicable rules. Of course, funds transferred to an RRSP or RRIF will be taxed upon withdrawal.”

While Seed thinks Ottawa would have been better advised to tweak the existing TFSA and HBP programs instead of creating the new registered account (and yet another new acronym!), he concludes the FHSA is “pretty great stuff” for young people looking to buy a first home.

Equally enthused is CFP and RFP Matthew Ardrey, wealth advisor and portfolio manager with Toronto’s TriDelta Financial. He says: “The FHSA is the home savings plan we were all dreaming of when we first got the HBP. Combining the best aspects of the RRSP, tax deductions for contributions, and the TFSA, tax-free qualifying withdrawals, this can be a game changer for the next generation of homebuyers in Canada.”

The beauty is that the FHSA removes one of the largest drawbacks of the HBP—the repayment or taxation of the withdrawal over the next 15 years following the withdrawal. “These repayments can be a burden on a new home owner as they are rebalancing their budget with many of the associated costs of home ownership.”

Ardrey estimates the FHSA lets participants save $46,415 toward a home within five years, assuming maximum annual contributions between 2023 and when the $40,000 lifetime maximum is reached, based on a 5% return. A couple can double that to $92,830, assuming home ownership is new to both.

“If the new home owner is going for a [Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation] CMHC-insured mortgage of an amount below $1,000,000, that is over a 9% down payment. This would let [young Canadians] buy a $920,000 home under current rules,” Ardrey says.

They could finance an even grander house if they combined the FHSA with the HBP. To get to the HBP maximum withdrawal of $35,000 in five years using the same 5% rate of return, the homebuyer would contribute about $6,000 per year to the RRSP.

That would mean a down payment of $81,415 for an individual and $162,830 for a couple with identical savings.

There’s more.

A homebuyer could take the tax refunds from the FHSA and RRSP contributions and put them into a TFSA.

Assuming a 35% tax rate, doing so generates a refund of $4,900 per year that could be put toward the TFSA. That creates an additional $28,430 (or $56,860 for a couple) over five years, for a grand total of $109,845 (or $219,690) for a hefty down payment.

Also, Ardrey notes, the TFSA doesn’t have to be directed towards the down payment, but can be used for anything else.

What if a young couple doesn’t earn enough to maximize all these vehicles? They could also tap the Bank of Mum and Dad (BOMAD). Nothing prohibits parents from contributing to TFSAs on behalf of their offspring. Some families I know incentivize their kids to save by “matching” TFSA contributions. For example, if Junior comes up with $3,250, the parents chip in a matching $3,250 to get the annual TFSA contribution up to the current maximum of $6,500.

Plus, neither I nor the sources I connected with for this column see any reason why prospective home owners couldn’t take money from their TFSAs, then contribute it to the FHSA. Then direct the resulting tax refund to replace some of the withdrawn TFSA funds.

“I see nothing that would prevent you from doing that,” Ardrey says. “You can take money out of a TFSA for anything and the room regenerates the next year.”

Hector agrees: “You could absolutely withdraw money from your TFSA and use it to fund your FHSA, then use the refund to replace a portion of the money that was withdrawn from the TFSA. As long as you are not over-contributing to your TFSA, of course.”

The TFSA withdrawal will provide a dollar-for dollar-increase to the available TFSA contribution room, but not until January 1 of the following calendar year.

I realize not everyone believes in home ownership and fewer still wish to be a landlord. Colleague Kyle Prevost, who pens MoneySense’s weekly “Making sense of the markets,” described his own disillusionment with residential real estate in a MillionDollarJourney blog he wrote in 2021. Prevost also wonders “whether it’s wise to help tie down young people to one geographical area if they’re still relatively early in their careers.”

However, as Hector points out, “The FHSA can be valuable even for life-long renters who have no interest in home ownership.” The FHSA can eventually be transferred into an RRSP or RRIF but when that transfer occurs, it does not require any traditional RRSP contribution room, Hector says: “As a result, the FHSA can be used as a way to get an additional $40,000 of RRSP contribution room.”

Assume you or your offspring do believe in home ownership as an investment (as I do myself). Even then, some retirees may balk at jeopardizing their own retirements to get their kids on the first rung of one of the world’s most expensive housing markets.

“Helping adult children is a noble goal: Just make 100% sure that your own retirement is taken care of first,” Prevost tells me. “It’s okay to be a little bit selfish!”

He adds that if parents can help their kids a little earlier in life, it’s likely to be much more helpful than providing a larger inheritance later in life.

Indeed, Michael J. Wiener describes on his Michael James on Money blog how the FHSA can be used to “give with a warm hand” rather than a cold one.

A final point is about how FHSAs are taxed upon death. Hector suggests this nuance may surprise some Canadians because it’s different from RRSPs and RRIFs.

“With an RRSP, if you name someone other than your spouse as the beneficiary, they are entitled to the full market value of the RRSP, and the tax is paid on the final tax return of the deceased,” Hector says.

However, with an FHSA, if you name someone other than your spouse as the beneficiary, the tax related to the FHSA is paid by the beneficiary. “It’s the opposite tax treatment, and this could really trip people up with their estate plans,” he says. “Of course, there are similar tax-free rollovers to a spouse, and you can name your spouse as either a beneficiary or a successor holder.”

So, while the FHSA may be targeted toward young Canadians to save up for their first home in a tax-efficient way, retirees with adult children should still know about it.

Jonathan Chevreau is the Investing Editor at Large for MoneySense. He is also founder of the Financial Independence Hub, author of Findependence Day and co-author of Victory Lap Retirement. He can be reached at [email protected].

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

You wrote: Who qualifies for the FHSA?

To qualify for the FHSA, you must be 18 years old, Canadian and be a first-time home buyer, but can only tap the FHSA once.

Do you mean “at least 18 years old”?

Hi Marie, Thank you for letting us know. You are correct. We have updated the article.

Does the hfsa apply to singles and if so can they continue the plan in the case they form a common law married relationship with a homeowner?

Due to the large volume of comments we receive, we regret that we are unable to respond directly to each one. We invite you to email your question to [email protected], where it will be considered for a future response by one of our expert columnists. For personal advice, we suggest consulting with your financial institution or a qualified advisor.

The FHSA is a gift and those with the available funds should jump all over it. It’s a no brainer. However, I would bet most will never use this money for buying a home. This inflated gas bag we call real estate in Canada (the most expensive in the world) is so overvalued that even a 50 percent correction at today’s prices would still leave housing prices elevated.