What Canadian investors can learn from the BlackBerry story

CBC’s new miniseries BlackBerry looks at the 2000s super stock, but we look at five takeaways for investors.

Advertisement

CBC’s new miniseries BlackBerry looks at the 2000s super stock, but we look at five takeaways for investors.

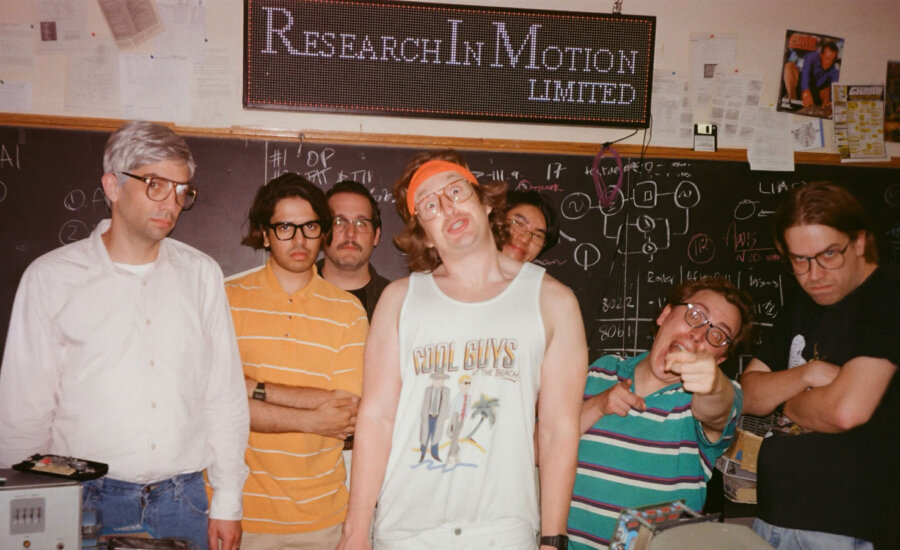

If you missed the acclaimed movie BlackBerry in theatres, it’s airing on CBC and streaming on CBC Gem as a three-part series—with additional scenes—beginning November 9. The limited series chronicles the making and unmaking of Canada’s global technology champion of the early 21st century. Entertaining as it is, the show also contains some important lessons for investing in technology startups. MoneySense spoke with Jacquie McNish, co-author of Losing the Signal: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry (Flatiron Books, 2015), the book upon which the series is based, about the takeaways for investors.

“We are a risk-averse country,” says McNish. “We are dominated by large corporations, whether in banking or technology or real estate.” BlackBerry—then known as Research in Motion, and RIM for short—only got noticed in Canada after it was backed by American investors and banks, and lauded by the likes of Bill Gates, Oprah Winfrey, Michael Dell and GE’s Jack Welch.

“That is something that as a country and as a marketplace we should fix,” she says. But until that happens, be realistic about how Canadian tech companies stack up against foreign, especially American, competitors that come by this support more easily.

BlackBerry is credited with inventing the now ubiquitous smartphone product category, but many other tech firms had already tried to merge cellphone technology and internet capabilities by the time it came along.

“For 10 years prior to that, the landscape was littered with failures by major companies. Even Apple in ’93 tried to do a message pad that would be transmitted over a network,” McNish says.

BlackBerry’s breakthrough came from finding ways to conserve network bandwidth. When wireless carriers instead switched to selling data, and bandwidth exploded, that advantage became moot. The new competition, Apple’s iPhone, promised pictures, maps, video—“things that BlackBerry said was an impossibility,” she says.

BlackBerry’s first big break came in 1997. “It had basically been blessed by a major telephone carrier in the United States as the future” when it introduced the first BlackBerry device, a pager called the Bullfrog, McNish notes. Apart from its appeal to consumers, BlackBerry offered carriers a mutually beneficial business proposition. The company’s market position began to crumble when it took those partnerships for granted.

When Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone in 2007, McNish says, “he also brought on stage a very important individual who was an AT&T senior executive who was offering billions of dollars for the exclusive right to sell the Apple iPhone for a number of years” as well as committing to upgrade the company’s network to handle the soaring volume of data that entailed.

Apple’s announcement proved a turning point. Jobs, who had earlier dismissed the idea of making a smartphone, tacitly acknowledged the market opportunity that BlackBerry opened up. “And then the second critical moment was when people started asking Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis, the two senior people at the top of BlackBerry, were they worried about it,” McNish says. “They brushed it off.”

Management needs to demonstrate that it’s aware of risks, it understands them and it is forthcoming about them. When Balsillie and Lazaridis finally began reacting to the iPhone challenge, that was when “they really started to stumble.” While researching her book, McNish recalls, “the company was eating dust and people were still romantically devoted to this device and could not accept that it was failing. That sort of cognitive dissonance existed at all levels, whether it was banking support, shareholders. And I think a lot of people, including investors, suspended disbelief.”

As the BlackBerry series shows, the contrasting personalities of the company’s co-CEOs was an asset in the beginning. But “by the time Apple came along, they were not speaking to each other, so it was very dysfunctional,” McNish says. “I think the board could have played a much bigger role in terms of their scrutiny, looking at the backdating of stock options, checking to see if there were risks.” BlackBerry would have benefited from a more diverse, independent board of directors with deep expertise in technology.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

So true as I was there during the rise and fall of RIM.

Can we rinse and repeat with Nortel Networks, please?