Why having a short memory can hurt investment returns

And why understanding "start date bias" can help boost portfolios

Advertisement

And why understanding "start date bias" can help boost portfolios

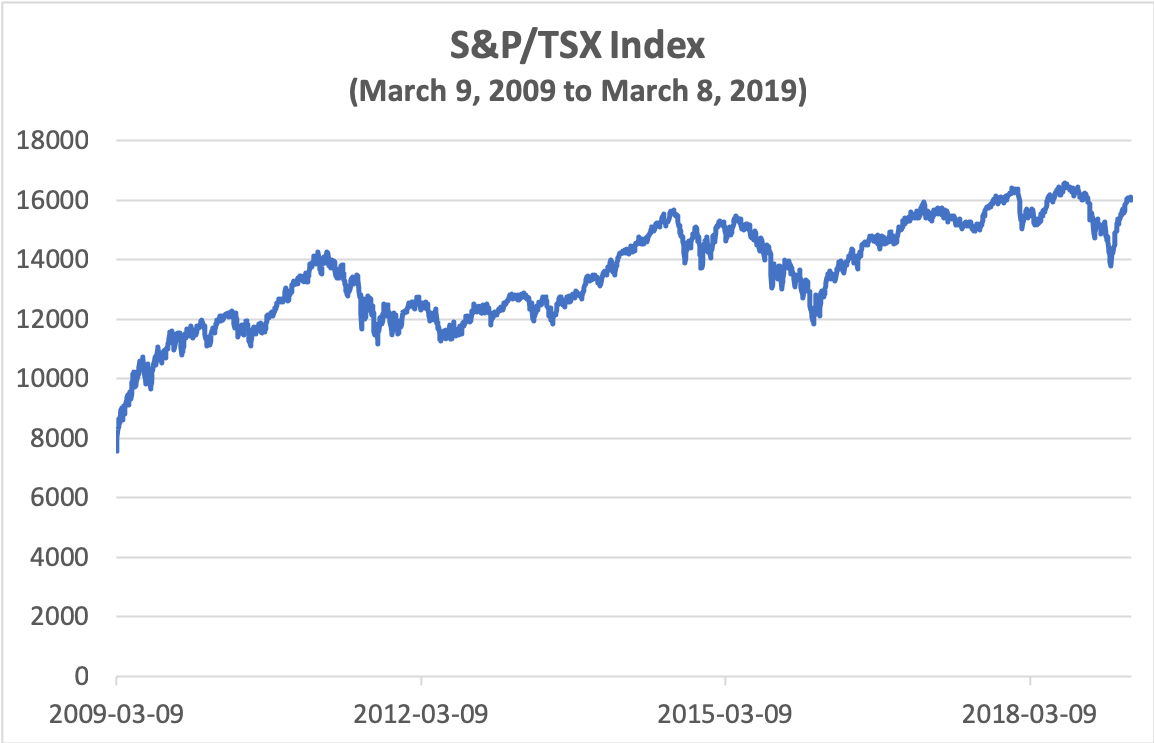

I’ll be showing the chart to clients as they come in for their portfolio reviews this spring. Just the facts. I’ll ask them to look at the chart and to tell me what they think it means. Speaking personally, I don’t think it means much. My random impressions and observations are as follows:

I’ll be showing the chart to clients as they come in for their portfolio reviews this spring. Just the facts. I’ll ask them to look at the chart and to tell me what they think it means. Speaking personally, I don’t think it means much. My random impressions and observations are as follows:

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email