Tontines in Canada: Moving from theory to practice as a solution to our retirement crisis

You may be hearing about new products that sound like tontines, even if they’re not called tontines. Here’s why.

Advertisement

You may be hearing about new products that sound like tontines, even if they’re not called tontines. Here’s why.

For years in his academic papers and some of his 17 published books, famed Canadian finance professor Moshe Milevsky described the history and theory behind a seemingly obscure retirement/longevity insurance structure known as the “tontine.”

Milevsky, who works at the Schulich School of Business at York University, has now partnered with Canadian financial services firm Guardian Capital LP to bring his theories to life as a commercial proposition: One that may help millions of retiring baby boomers, and ultimately those who follow them, to overcome the anxiety of outliving their money. This guide will show you what tontines are, how they work and which tontines are available for Canadians. It can also help you research the best tontines for you and your situation. But, first…

Tontines can be compared to life annuities—or for that matter, defined benefit pension plans. A tontine works by pooling savings from multiple investors. Essentially, those who die earlier subsidize the lucky few who live longer.

Asked for a simple definition of a tontine, Guardian Capital managing director and head of Canadian retail asset management Barry Gordon said it is “a pool of assets that are shared by survivors over time.” In that respect, annuities and defined benefit pensions operate similarly, he said. Indeed, for Guardian Capital, a driving force was the lack of availability of defined benefit plans these days.

The concept has been around for hundreds of years but it fell out of favour in the 1900s, as it was seen as profiting off of others’ deaths. However, with some modifications, like paying dividends throughout the lifetime of the pooling investors, tontines may become popular again.

Tontines have a long and controversial history. The Globe and Mail recently described the tontine as “the most discredited financial instrument in history,” while asking whether its comeback could solve the retirement income crisis.

Tontines have also shown up in popular culture, notably in the 1966 British comedy The Wrong Box. A favorite film of Milevsky’s, it takes a sardonic look at a group of people willing to indulge in skulduggery in order to eliminate the “competition” and outlast their rivals. It’s an insurance take of the reality show, Survivor. Another popular TV show, The Simpsons, explained how tontines could save Abe Simpson from ending his days in an “old-folks home.”

Milevsky’s recent book is called How to Build a Modern Tontine (May 2022). It’s a mathematics-laden guidebook for investment and insurance professionals interested in actually creating a real-world implementation of a workable tontine product.

In an email to me last week, Milevsky wrote: “You and I have talked many times about tontines as a possible solution for retirement income decumulation versus annuities. Until now, it’s all been academic theory and published books, but I finally managed to convince a Canadian company to get behind the idea.”

Toronto-based Guardian Capital LP announced in early September a partnership with Milevsky, unveiling three “solutions” based on his ideas. One is a pure tontine solution, another a more traditional decumulation vehicle, and the third a best-of-all-worlds hybrid of the two. More on that below.

Demographic forces argue in favour of these new solutions. As a Guardian Capital backgrounder notes about the retirement dilemma, nearly one in five Canadians is now a retiree, and the number of Canadians aged 85 or older has doubled since 2001 and could triple by 2046. The culprits for retirement insecurity are familiar to most readers: stubbornly low interest rates—at least until recently—and the continuing erosion of traditional employer-sponsored defined benefit pension plans.

In a guest post for my own website, Milevsky writes that “nobody really ‘runs out of money’ in retirement in the 21st century. That is plain utter fear-mongering nonsense.” Apart from the Canadian Pension Plan (CPP), Old Age Security (OAS) and Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), investors can get over 4% a year on strip bonds or five-year guaranteed investment certificates (GICs). “The primary objective isn’t a guaranteed lifetime of income, which anyone can create with a simple discount brokerage account and a DIY instruction manual. The goal is to get the HIGHEST possible income and at the LOWEST possible cost.” That’s his case for these tontine retirement solutions.

So without further ado, let’s look at the two dominant tontine-like solutions available in Canada, starting with the Purpose solution from 2021.

Guardian Capital’s entry into tontines follows the pioneering Purpose’s Longevity Pension Fund (LPF) from Toronto-based Purpose Investments Inc. Unlike Guardian Capital, which chose to explicitly use the tontine in its product name, Purpose did not. Milevsky says he is happy to give credit where credit is due to LPF for “opening the door” to tontines, and that “Guardian is opening the door wider.”

LPF passed its first anniversary in June this year. And according to Longevity Retirement Platform president Fraser Stark, it has attracted 400 investors so far. That’s roughly one new sign-up per day. It has attracted $14 million into the fund so far.

Like Guardian Capital, LPF takes a mutual fund approach to the problem, with two classes of funds: One an accumulation class for those under 65; the other a decumulation class for those over 65.

Stark says three quarters of LPF investors opt for the accumulation vehicle, while the other 25% choose the decumulation version, but assets skew about 70/30 to decumulation, because the investments are larger.

“We’re getting interest from people in their 30s and 40s via workplace savings programs,” Stark tells me, “Until age 65, the fund behaves like a traditional balanced fund, with no longevity risk pooling.”

Typically, LPF investors put one-third of their total portfolio into the fund, creating an income stream that can go toward most of their retirement needs alongside CPP and OAS.

Stark says most of the money comes from registered assets, including registered retirement saving plans (RRSPs) or registered retirement income funds (RRIFs), for those converting in their early 70s. The product’s income levels are structured to be in line with annual RRIF minimum payments, which rise each year as the account holder ages.

A report by LifeWorks (formerly Morneau Shepell) notes LPF has three main objectives:

At launch, Purpose targeted an initial 6.15% annual distribution. It describes LPF as “a pooled open-ended mutual fund, which has an objective to provide income-for-life to its unitholders paid through monthly distributions, where each unit pays a set distribution amount.”

Those initial distribution levels are not guaranteed and, depending on markets, they may rise or fall over time. In a kind of Monte Carlo simulation, LifeWorks generated 2,000 possible outcomes over a 40-year time horizon. It concluded “a conservative initial distribution level is shown to be both sustainable over unitholders’ projected lifetimes and has higher potential to increase over time compared to a best-estimate initial distribution level.”

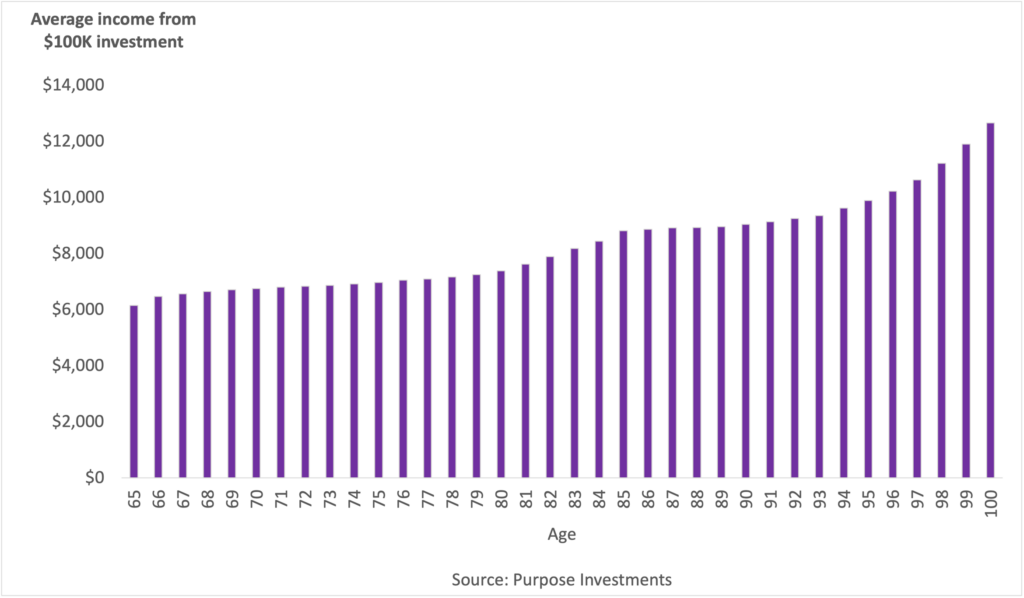

The accompanying chart shows average income from LPF expected across the 2,000 Monte Carlo scenarios prepared by LifeWorks.

Tontines are legal in Canada and most of the United States, and in some countries like Australia, but have long suffered from a perceived stigma often depicted in fiction. They are not legal in two U.S. states due mainly to outdated legislation. Interestingly, tontines are said to be the basis of the original life insurance industry and, by 1900, represented 7% of all private wealth in the U.S.

“Canada leads the U.S. and leads the world in the sense of broad retail availability. Our innovation was to embed the structure in a mutual fund,” says Stark. Think of Purpose’s product as a lower-case tontine, and Guardian Capital’s as a tontine with a capital T. Guardian Capital confirms that securities regulators in all Canadian provinces have given it the required “exemptive relief” under N181-102 (which lets it redeem at values other than NAV) and have all signed the prospectus issuing the securities.

In fact, Purpose is welcoming the competition from Guardian Capital. One unicorn product is hard to get our heads around, but two suggests a trend that the public can latch on to. Canada is well ahead of the United States in offering these types of commercial tontine products, says Stark, and Purpose is exploring with U.S. regulators taking the concept south of the border.

For retail investors, the main and perhaps only way to buy these types of tontine-like products—including Purpose Longevity Fund or the three new solutions from Guardian Capital—is through dealers licensed to sell mutual funds (MFDA and IIROC) across Canada.

Guardian Capital hints at innovation with its new tontine. “With our modern tontine, investors concerned about outliving their nest egg pool their assets and are entitled to their share of the pool as it winds up 20 years from now… Over that 20-year period, we seek to grow the invested capital as much as possible to maximize the longevity payout,” according to Guardian Capital’s Gordon in a press release.

Investors who redeem early or pass away leave a portion of their assets in the pool to the benefit of surviving unitholders, boosting the rate of return. “All surviving unitholders in 20 years will participate in any growth in the tontine’s assets, generated from compound growth and the pooling of survivorship credits,” according to Gordon in a news release. “This payout can be used to fund their later years of life as they see fit, and aims to ensure that investors don’t outlive their investment portfolio.”

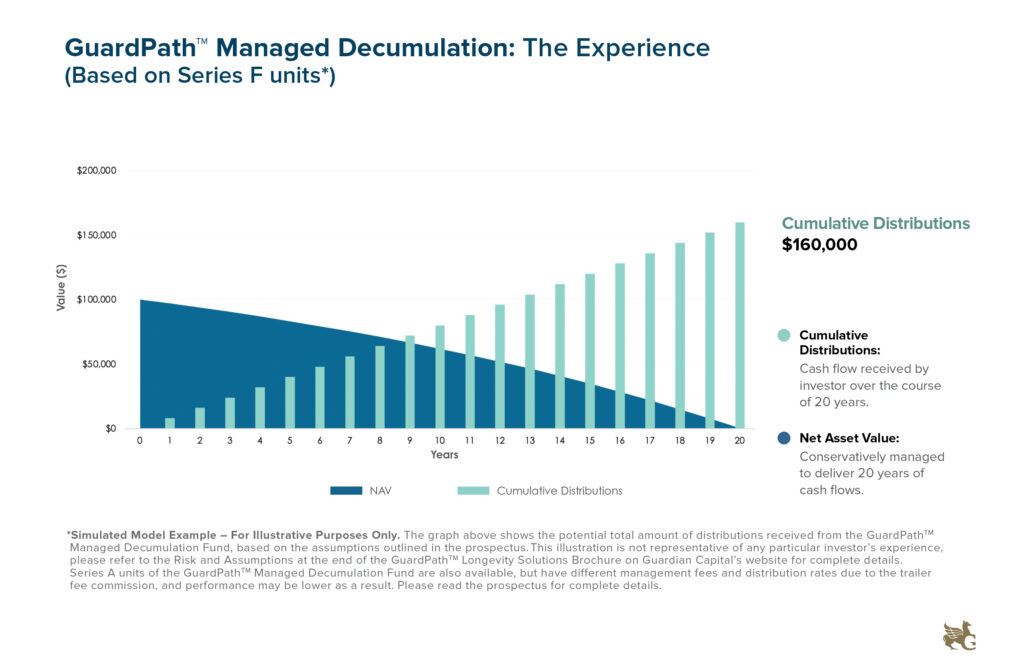

GuardPath Managed Decumulation 2042 Fund, the first of its three offerings, is not a tontine but essentially a balanced mutual fund. It delivers cash steadily over 20 years through risk management techniques aimed at extending portfolio longevity. As the first of the three accompanying charts illustrates, an initial $100,000 investment steadily declines over the 20 years, while over the same time, cash flow is received each year, totalling $160,000.

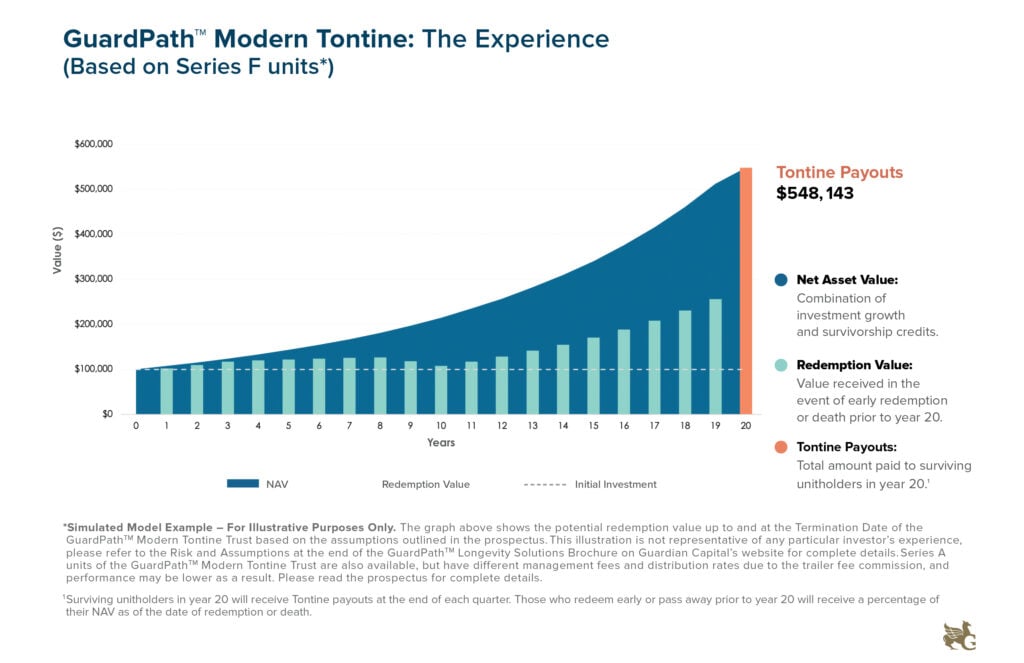

The second fund, GuardPath Modern Tontine 2042 Trust, is an actual tontine. It’s designed to provide financial security to retirees in later life, with significant payouts to surviving unitholders in 20 years based on compound growth and the pooling of survivorship credits for the eligible cohort of investors born between 1957 and 1961.

The second chart shows total tontine payouts of $548,143 (again on an initial $100,000 investment) for those who live the full 20 years, assuming an annual net return on the portfolio of 6.92%. The light-grey smaller bars show the value in the case of death or early redemption, which is projected to remain above the initial $100,000 in this example scenario.

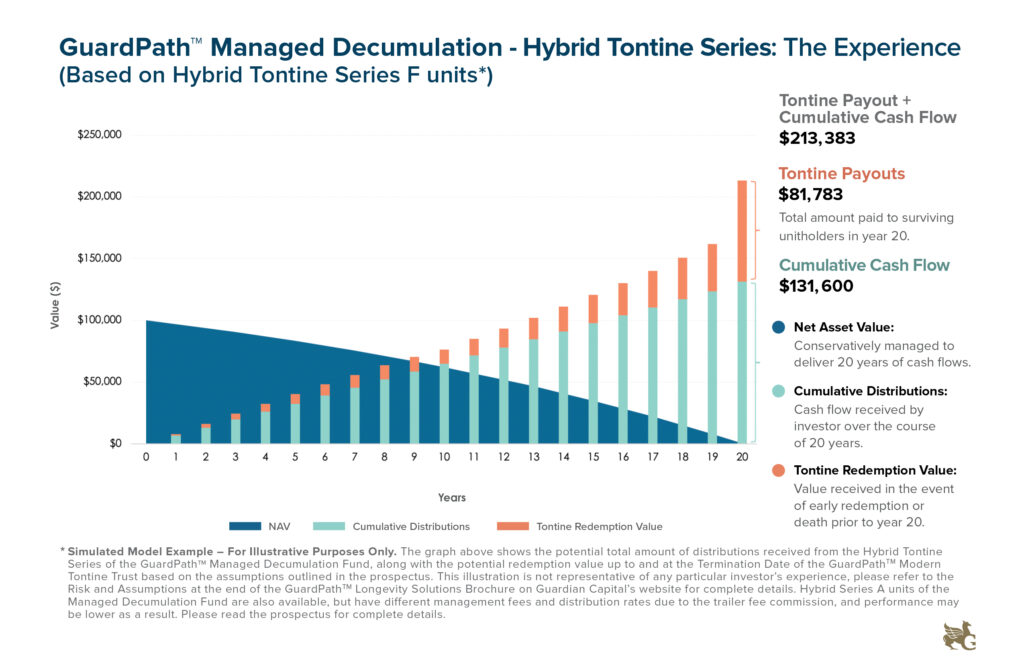

The third, the GuardPath Managed Decumulation/Hybrid Tontine Series, is perhaps destined to be the most popular as it combines the first two in a best-of-all-worlds solution. It is designed to provide “a holistic solution for the entirety of retirement,” according to the release. This combined product is said to generate steady cash flow for 20 years and provides significant payouts to surviving unitholders in 20 years.

Gordon tells me he agrees with Purpose’s assessment that having two firms launch new tontine products is “a great thing for Canada.”

Reaction to the early September launch of GuardPath has been “overwhelmingly positive,” says Gordon, adding that it’s a refreshingly different approach that addressed a real need for aging Canadians.

Like Purpose, Guardian Capital created tontines with a mutual fund structure with its GuardPath assets. That structure provides control over who joins the fund and the fund can be monitored if anyone leaves. Guardian Capital’s managed decumulation fund does have an ETF series, but is not available as the hybrid tontine series.

For each $0.80 paid out annually, the GuardPath Managed Decumulation/Hybrid Tontine Series is divided into the two components: $0.65 goes to the investor and the other $0.15 is invested in units of the tontine trust. This is a form of dollar-cost averaging.

Thus, the hybrid investor receives significant yearly cash flow along the way and is investing in the tontine as they get older So, $0.65 a year is targeted cash flow and $0.15 in the tontine, all proceeding in parallel over 20 years—not serially over 40 years.

Is it possible to have a different mix than the hybrid 65/15 split?

“Sure you can; just buy the two instruments separately,” Gordon tells me.

If you read Milevsky’s book or the marketing material by Purpose or Guardian Capital, it’s clear there are no absolute guarantees with tontines. Gordon says its modelled illustrations are conservative, aiming to underpromise and hopefully overdeliver. “As soon as you have guarantees, there are significant costs and payouts would be reduced accordingly.”

TriDelta Financial wealth advisor and vice president Matthew Ardrey says the big difference between Guardian and Purpose is the annual income paid.

“Purpose pays income annually to the investor, and it is for life,” he says, adding that it is more like an annuity. “If an investor withdraws or dies, they receive the remaining capital invested—capital invested minus payments taken—but all the gains remain in the fund.”

With Guardian, a lump sum payout comes in four tranches in the final year, and “if you die early or withdraw, you can lose up to 50% of the value of your investment.”

Ardrey shares that both products have to be geared towards the right person with longevity concerns or as only one piece of their total retirement plan. There is liquidity and redemption risk in both of them, so investors “must be sure they are ready to lock up their money.”

While some may be put off by the fact the more people who die or quit the better off the remaining investors are, Ardrey says he also sees benefits in specific circumstances, such as a family history of life longevity.

“First, these have to be funds that they can afford to set aside for the next 20 years,” Ardrey says, in the case of Guardian’s tontine. “If that condition is not satisfied, then there is no point in proceeding. Assuming that is the case, then the investor can take the bet on their own longevity for a bigger payout at the end. The risk is if they die or exit early, they or their estate get a reduced value.”

Advisors have long been tasked with helping baby boomers accumulate wealth. The tide is shifting now as boomers retire. As a result, the financial industry is watching the development of these tontine products closely to try to assess how they might fit into their clients’ retirement plans.

Guardian Capital developed the products for financial advisors and retirees, and it reports that there has been significant interest from advisors since launch.

“I’m a big supporter of the Purpose product,” says John De Goey, senior investment advisor and portfolio manager at Wellington-Altus Private Wealth Inc., “It is innovative and overdue. Accepting the usual disclaimer that everyone’s circumstances are unique and you should consult a qualified professional before buying, I was delighted when it was launched because longevity risk was one of the last ‘unsolved challenges’ of financial planning.”

The FP Canada Research Foundation Board (on which De Goey serves) commissioned research on why Canadians overwhelmingly take CPP early. A major reason is that “collectively and in general we severely underestimate how long we’re going to live. That’s ironic, given how the industry is constantly after people to take a long-term view. Risk pooling in three-year cohort groups/pools is a big innovation and is only possible in a mutual fund structure.”

De Goey has yet to look closely at the new Guardian Capital funds.

Guardian’s Gordon sees the GuardPath funds as appropriate for both registered and non-registered accounts, adding that a tax-free savings account (TFSA) “could be an ideal tax-deferred structure to own the tontine.”

However, the managed decumulation cash flow is expected to be pretty tax-efficient over 20 years, giving you capital gains, dividends and return of capital, so “I could definitely see owning that in a taxable account.” As for registered money, people need to pay close attention to how much they put in RRSPs or RRIFs, he advises.

Since RRSPs are eventually converted to RRIFs, there’s a danger that if you own too much of the tontine product in a RRIF, “the mandatory annual RRIF withdrawals may mean you have to redeem some of the tontine units, which has a redemption penalty. So I wouldn’t want to own too much of the tontine in the RRSPs converting to a RRIF… The managed decumulation fund is ideal for a RRIF.”

As with any investment, there are always risks to consider. Aside from the obvious one being an early death, there is considerable liquidity risk, warns Ardrey.

In the case of Guardian’s tontine, he says that withdrawing early results in a penalty. “It is 5% in the first four years and then increases 5% per year until it reaches 50%, 10 years out. So, an investor must be certain of this decision.” Purpose reports that with its LPF, the same “money back” concept applies regardless of when you invest.

There is also investment risk, according to Ardrey. “The results are not only dependent on the remaining members of the tontine, but also the returns from the portfolio. So, depending on the performance of the tontine’s investment managers, you may be better or worse off than if you invested somewhere else.”

Financial planner Jason Pereira, senior partner and portfolio manager with Toronto-based Woodgate Financial, has yet to put any clients into either company’s tontine solution.

“Do I foresee using them in my practice? Absolutely.” He views them as an important innovation in “longevity planning.”

“We are in the very early innings of what could be a very important product,” says Pereira. “The issue for me is what is the framework for deploying capital to this type of product versus the alternatives. How much of client portfolios need to be allocated to reduce the risk of substantial ruin?” He calls tontines “a long-tail solution” that needs to survive long enough for its popularity to increase.

Another risk? Tontines just may not end up being a popular investment tool. The main obstacles Pereira calls out are advisor education and then client education. It may be difficult to get past the idea of profiting from a person’s death, even if that’s in effect what annuities and even defined benefit pensions do. He expects some clients to balk at any early redemption penalties, meaning they may only get back a percentage of what they put in. And there’s the endowment effect that also impacts annuities: giving up something if you die prematurely.

Generally, it could be said that it’s healthy people with good genes who are interested in longevity insurance, whether it’s with annuities or tontines. Pereira says these products are hard to get on advisor shelves because of due-diligence requirements and dealers will have to be educated on the concepts. Meanwhile, bank branches are moving to full proprietary product shelves.

“There’s immense value in this concept: the longevity of the Boomers is absolutely a problem,” Pereira concludes. “The issue is the concept needs to be proven and people need to understand it. I believe if they can sell enough to survive and start to issue mortality credits and people see the benefits, then advisors will perk up.”

MoneySense Investing Editor at Large Jonathan Chevreau is also founder of the Financial Independence Hub, author of Findependence Day and co-author of Victory Lap Retirement. He can be reached at [email protected].

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

Using a Simpsons reference made me love Money Sense even more – thank you LOL