How ADHD can affect your finances

Ellyce Fulmore struggled with impulsive spending and debt—until she figured out money strategies that work with her neurodivergent mind.

Advertisement

Ellyce Fulmore struggled with impulsive spending and debt—until she figured out money strategies that work with her neurodivergent mind.

Financial advice has never been one-size-fits-all, but if you’re neurodivergent—meaning that your mind absorbs and processes information in an atypical way—you might have to bend it to fit your own needs. That was true for Ellyce Fulmore. Since 2020, the Calgary-based finfluencer has shared witty insights on how having ADHD has affected her financial well-being. (In one Instagram post, she assures viewers, “It’s not you, it’s the dopamine deficiency.”) Fulmore has launched the financial literacy company Queerd Co., and earlier this year, she published the book Keeping Finance Personal: Ditch the “Shoulds” and the Shame and Rewrite Your Money Story (Hachette Go, 2024). It’s a funny, wise and refreshing read for anyone who struggles with following conventional tips for money management. Read the excerpt below for a taste of Fulmore’s unique voice and perspective, and don’t miss her My MoneySense Q&A.

—MoneySense Editors

ADHD stands for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The American Psychiatric Association defines ADHD as a “developmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.”

The name is misleading because people with ADHD don’t necessarily have a deficit of attention, but rather, the inability to focus their attention.

ADHD coach Brett Thornhill says, “It’s like your brain keeps switching between 30 different channels and somebody else has the remote.”

The stereotypical view of someone with ADHD is a hyperactive boy who can’t pay attention in class, has seemingly endless energy, and is constantly moving, fidgeting, and talking. But ADHD is also the person with their head in the clouds, the daydreamer. They are easily distracted and have problems sustaining their attention. With ADHD you can present more hyperactive symptoms, more inattentive symptoms, or have a balance of both. In addition to these types, ADHD exists on a spectrum and can impact people in different ways, to varying degrees. All three types interfere with the individual’s functioning in multiple settings. ADHD is very real, very challenging, and can often be debilitating.

I have the combined type of ADHD, so I experience both hyperactive and inattentive symptoms without one of those being far more prevalent. While I did well in school, almost every report card mentioned that I was a chatterbox. When I wasn’t busy talking, I was staring out the window, doodling, or working on homework for another class. None of these behaviours was flagged as a problem because of my grades. This is often what happens to women and girls with inattentive ADHD.

Since my moment of free-falling, I have found solid ground. I’ve built a successful business, transformed my financial situation, and found myself in the happiest, healthiest relationship I’ve ever had. It turns out the problem was never me, or my undiagnosed ADHD, but the fact that society is not designed to accommodate anyone who diverges from the norm. Of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that my privilege greatly contributed to this outcome as well.

In this chapter, we are going to touch on some of the common challenging aspects of managing money with ADHD, and how you can work with your brain instead of against it. I want to acknowledge that there is a lot of research currently being done on ADHD, especially in women, so some of this information might change as new discoveries are made. It’s important to note that everyone experiences their ADHD differently, and some of the money struggles I talk about won’t be applicable to you. Whether you’re reading this chapter for yourself, or to support someone else in your life with ADHD, give yourself the space and grace to experiment and find what works.

I opened up a $10,000 line of credit when I was in college to help cover some of my expenses as a student. I remember thinking to myself I’ll only use like $1,000 and pay it off once I’m back at my full-time summer job. But it only took me two months to max out that $10,000 line of credit because I couldn’t stop impulse spending.

Yes, I know, I’m wondering how that was possible too. Prior to my diagnosis, my brain was feeling so out of it most of the time that I would spend money just to feel something. This line of credit was the gateway to even more spending, and before I knew it I had a maxed-out credit card, two lines of credit, and my student loans.

This is how I ended up in $35,000 of debt, $15,000 of which was high interest. I would look at my credit card statement and not even remember half the purchases I made. It seemed like everyone around me had it all figured out, and here I was, free-falling.

The shame I felt followed me everywhere: when I went out for dinner with my friends, paid for my groceries, treated myself to a Starbucks, or bought another shirt that I definitely did not need. I felt so out of control, but at the same time I didn’t know how to change my money habits and behaviours.

Turns out, my struggle with impulse spending and debt was not a unique one. 65% of folks with ADHD say that having ADHD makes managing their money more difficult.

If you have ADHD you are…

…than those who don’t have ADHD.

ADHD isn’t confined to one area of your brain or one major impact on your life. It affects how you take in sensory information, how you think and process, and how you respond and behave. When it comes to your finances, it’s going to impact how you understand, spend, and manage money. It will influence your emotions and mood, which we know both play a big role in financial decisions. Our challenges can lead to earning less and paying more than folks without ADHD. Just like every other chapter in this book, understanding how this piece of your identity impacts your money story, behaviors, and patterns is crucial for changing your situation.

When I was first diagnosed and started to learn more about how certain traits affected my money, I looked online to learn more. I was met with tumbleweeds, a couple YouTube videos and vague articles, but nothing that I could relate to. In fact, many of the articles giving advice on ADHD and money were filled with tips like “just make a budget” or “stop impulse spending.”

Thank you, Janet, I never thought of that!!

Much of the advice available completely misses the mark because it suggests using systems and tools designed for and by neurotypical folks instead of actually catering to neurodivergent brains. For those of you unfamiliar with those terms, “neurodivergent” refers to those whose brain and cognition differs from what is considered “typical” by society. This can include folks who have ADHD, autism, dyscalculia, dyslexia, dyspraxia, BPD, and more. The term “neurotypical” describes those who display “typical” cognitive function. Please be aware that this language is always evolving, and new terms might be in use by the time you read this book.

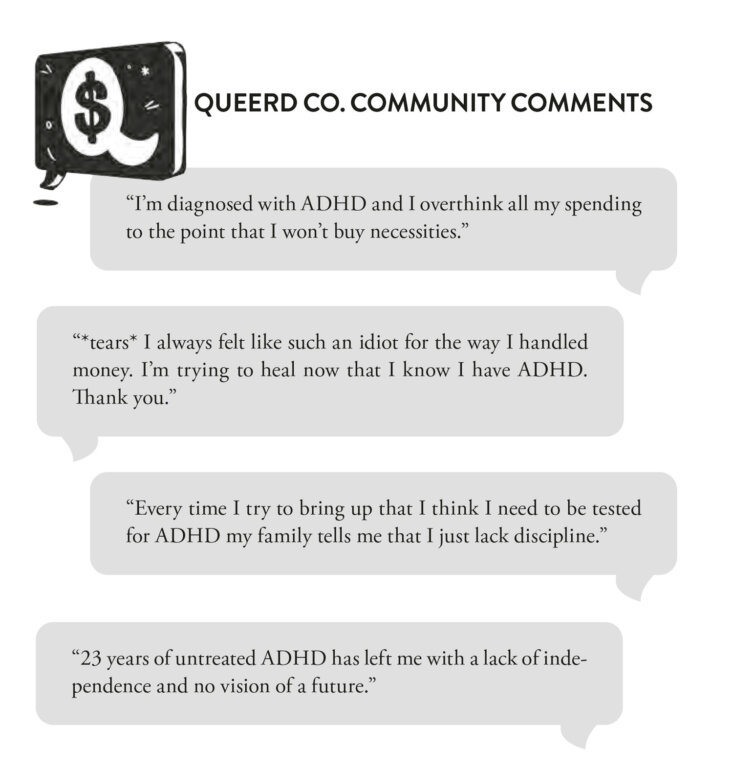

To fill the gap I had identified, I started creating content around how my ADHD impacts my finances. If you follow me on social media, you know I talk about ADHD and mental health on an almost daily basis. I’ve had multiple videos on ADHD and money go viral, and here are some of the comments I have received:

I hope after reading these comments, you know that you’re not alone. I hope you feel validated, that it’s not just you struggling with your money. I hope you know that your financial challenges are clearly not your fault. I’ve said that a lot throughout this book, but I will say it a million more times in an attempt to override society’s overarching message that your struggles are solely your problem.

Despite me saying all that, I know there will still be some of you who don’t believe me. You still feel like you’re lazy, not motivated enough and a failure. A lot of that stems from the misconceptions and lack of understanding that still exists around ADHD. To combat that, I’m going to share some of the common beliefs people with ADHD hold and the reality behind what’s actually happening. I want you to understand that there are real, tangible reasons that your finances are suffering and that there are actionable steps you can take to change that.

Writing this book brought up a lot of shame for me. When I signed my book deal, I had a long time frame to complete the manuscript, almost a full month to write each chapter. I planned out a schedule for exactly how I was going to spend my time. I decided I would write a little bit throughout the week and then Fridays would be my dedicated writing day.

The plan was perfect, but I couldn’t stick to it. I know that my brain thrives off urgency, and I do my best work under pressure. Having almost a year to write this book with no real sense of priority didn’t set me up for success. I’m writing most of this book in the last two months before my manuscript due date. Some might label me as lazy for putting it off, but I couldn’t create that false sense of urgency for myself. I had to wait until the tension of the deadline closed in around me. I felt deeply shameful about this. I was embarrassed when people asked me how writing was going. There were low moments of beating myself up, calling myself lazy. But I’m not lazy, I just have ADHD.

ADHD impairs your executive function, the set of cognitive processes involved in planning, time management, prioritization, organization, and self-control. Executive function is what enables us to effectively accomplish what we want to do and reach our long-term goals. It’s basically the manager of your life. When your executive function is impaired, this will directly impact your ability to organize your money and stay on track with financial goals. The general detriment to planning and time management will have other indirect effects on your finances as well.

If you have ADHD, I’m sure you have experienced couch paralysis. This is when you’re stuck on the couch, scrolling on your phone or watching TV and just cannot seem to get up and do the thing. You want to go work, or study, or clean your house because it’s important to you, but you feel glued to those cushions. Growing up maybe you were called lazy for this. Maybe your partner gets frustrated when they ask you to do something and come home to find you watching TV on the couch. You’re not lazy, you just have ADHD.

Executive function has effectively left the building. The task you are faced with might have too many moving parts that involve your executive function, which can hold you hostage. I want you to think about when you may have experienced this situation around your finances.

Let’s look at the earlier example from Janet, telling folks with ADHD to “just make a budget.” Making a budget is seen as one of those tasks you “should” be doing. It’s what all the financial experts tell you to do and seems pretty straightforward, right? For someone with ADHD, this “straightforward” task can end up being very overwhelming. Here’s an example of what this might look like:

Some of you may not struggle with budgeting and actually find this an enjoyable task, but you can likely relate to this example when it comes to one or more areas of your finances. Tasks that other people can just sit down and complete may feel like climbing a mountain for you. Creating a budget involves your executive function, which is partially out of commission. So sometimes it’s easier to just avoid the task completely.

Repeat after me: “I’m not lazy, I just have ADHD.”

One of the big reasons folks with ADHD struggle with their finances is because they lack the right motivation. You know you “should” be saving money, paying off debt, and planning for the future, but you can’t seem to execute on those goals. You might find yourself constantly comparing your financial progress with that of others and being frustrated that you haven’t reached certain milestones. Other people are doing all the things, so why can’t you? This often leads to the belief that you just need to be more motivated, or have more willpower. But motivation is not the problem, it’s that you’re seeking the wrong kind of motivation.

Neurotypical folks respond differently to “shoulds.” They can tell themselves that they should save up a safety fund, or that it’s important for them to be investing for retirement and just go and do those things. Wild, right? As someone with ADHD, even if I know something is important, and I want to do it, it can still be a challenge to find the motivation to start and keep going.

Dr. Russell Barkley accurately refers to ADHD as “a motivation deficit disorder.”

We are lacking the same motivation that neurotypical folks have and often don’t like tasks that are boring, repetitive, or take a long time. Don’t worry, this doesn’t mean that you’ll never be able to do these tasks, it just means that you need to tap into different types of motivation. Let’s cover four common types of motivation for folks with ADHD, and later on I’ll touch on how you can apply them to your finances.

The reason why the long writing deadline didn’t work for me was because I had no sense of urgency. This is why many folks with ADHD will procrastinate on tasks. Waiting longer will create pressure and drive for them. You can either manufacture the urgency or tension yourself, or in some cases, rely on that from others.

Pressure from yourself often shows up in the form of shame, anxiety, and negative self-talk. Raise your hand if you’ve ever shame-spiraled so hard that it motivated you to complete the task you were avoiding. Whoops—me too. Pressure from others can stem from your fear of failure, disappointment, or potential consequences. It can also be rooted in your desire to impress or please others. When my university friends all met every day to study, they expected me to be ready to be quizzed, and that created pressure that motivated me to show up prepared. This type of tension is way more up my alley because, while I will ignore my own deadlines, I hate letting other people down (recovering people pleaser over here!).

We can also experience financial pressure, when the fear of your money being at risk creates a sense of urgency. That’s the whole premise behind late or cancellation fees. Businesses hope that the financial repercussions of not showing up will be enough to deter that from happening. It’s a good thought, but I’ve noticed the financial pressure will vary based on the individual’s perception of that “cost.” For example, a cancellation fee of $5 is unlikely to stop me from canceling if I need to. I’ll take the hit because $5 isn’t a lot of money for me. For other people, that $5 means more and they might respond differently.

Now, pressure or urgency may not do it for you, and that’s okay because we have three more types of motivation coming up.

Have you ever put off cleaning your house or cooking yourself a meal because you were too busy reading a good book? Or researching how to transport coral from a saltwater fish tank (my most recent google search)? Or spending hours perfecting your latest crafting project? You have no problem spending the whole day doing these things, while simple daily tasks feel impossible.

This is why it’s more accurate to say that folks with ADHD have an inability to focus their attention rather than a deficit of attention. You can easily engage and zero in on the tasks that interest you but struggle to even initiate the tasks that don’t. We know that people with ADHD can fixate for hours on end when it comes to tasks they find engaging. Often the repetitive and necessary tasks required to take care of ourselves, our living space, and our finances get pushed to the wayside. The challenge here is to find a way to make those less riveting tasks more personally interesting.

For example, I don’t love doing the dishes. But I make this task more enjoyable by using a Scrub Daddy sponge (which I love) and listening to music or watching a show while I do them. You may not be able to make a task like filing your taxes more enjoyable, but perhaps you can do it in a way that’s more interesting.

With this type of motivation, we are aiming to turn those tasks you’re avoiding into a competition or challenge, essentially gamifying the process. I notice this motivation the most when I’m doing a Peloton bike ride. During the class, there is a leaderboard on the side of the screen that shows everyone else on the ride. I usually keep this hidden, because if I glance at the leaderboard I suddenly feel the need to beat everyone. I suppose that’s not a bad thing, but I’m not looking to pass out on every bike ride I do. Keep in mind that even competing against yourself and the idea of beating your personal best can be motivating. Competition and challenge tends to be hit or miss with ADHD folks. Either you love it or you hate it.

You know that feeling when you buy a cute new gym outfit and suddenly you have more initiative to exercise? That’s novelty motivation at work. Your brain is stimulated by fresh and novel things, and you’ll get a hit of dopamine from starting exciting tasks. The challenge is that once that novelty wears off, you will lose that source of motivation. This is why many folks with ADHD get excited about new hobbies or ideas and end up abandoning them before they finish. RIP to all my 70%-finished projects. The key here is to find different ways to keep the task fun and fresh until completion.

Trying to accomplish tasks that we see others doing easily, or that we’ve completed before in the past, can be very frustrating. It’s no wonder we internalize the belief that we are lazy, or that we just don’t care enough. But it’s not about trying harder, or caring more, or being more disciplined. It’s not about contorting yourself to fit into society’s neat little boxes. It’s about accepting that your brain has different needs. Your brain has less dopamine and requires more stimulation. You don’t need to change—your approach to the task does. That’s when you’ll find the motivation that’s right for you.

Repeat after me: I don’t lack willpower, I just have ADHD.

The day I took stimulant medication for the first time was like the day I put on glasses for the first time. I felt like superwoman. I remember going to the gym and realizing I could actually keep track of reps. Usually I’m like 1, 2—What am I going to eat after this?—5, 6, 7—Why is this person standing so close to me?—8, 9—Oof, this burns—9, 10—Wait, did I count right? But on medication I could count without losing track, and actually focus on my muscle activation. I always say that without medication I have “bees in my brain.” If you also have ADHD, you probably know exactly what I’m talking about.

Okay, now imagine unmedicated me—the person who has bees swarming around her brain, who can’t count to ten reps without losing track—trying to sit down and manage her finances. I hope you’re imagining an absolute disaster because that’s what it was. I never understood just how hard it was for me until I started taking medication and experienced what it was like to have a quiet brain for once. And it wasn’t until this realization that I also began to understand the profound influence that the right tools could have.

If we look at the research around ADHD and money, the conclusion might be that people with ADHD are bad with money. You’ve probably thought that about yourself at one point in your life because you’ve likely struggled with finances. According to research, adults with ADHD:

I’m not contesting that having ADHD contributes to financial challenges. But these challenges are not because people with ADHD are less smart, or incapable of making good financial decisions.

Symptoms such as disorganization, forgetfulness, unreliability, trouble planning, challenges with task completion, and poor time management contribute to difficulty paying bills on time, creating and sticking to a budget, managing cash flow, and maintaining good money habits.

“ADHD symptoms essentially increase the cost of self-control needed to perform various tasks that are necessary to maintain good financial health.”

It’s not that you’re bad with money, but rather that you don’t have the right tools to support you. If I put a bowl of soup in front of you and handed you a fork, you’d be like—what the heck, Ellyce, I clearly need a spoon. You recognize that trying to eat soup with a fork is ineffective and silly. That doesn’t make the soup inedible or the fork a useless utensil, they just aren’t the right fit for each other. The reason you haven’t had success with traditional finance advice and tools as someone with ADHD is because they were all designed for the neurotypical brain. You were handed a fork and told to eat your soup, only to realize that everyone else is eating a salad.

The key to managing money as a neurodivergent person is to find the method and techniques that work for your brain. Medication was one tool for me but so was creating an engaging budgeting system, learning how to inject dopamine into my money goals, and understanding what type of motivation works for me. Accept that it may take time to find what works and that doing things differently is not a bad thing.

Repeat after me: I’m not bad with money, I just have ADHD.

Excerpt from Keeping Finance Personal: Ditch the “Shoulds” and the Shame and Rewrite Your Money Story by Ellyce Fulmore. Copyright 2024. Available from Hachette Go, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email