Better crisis next time

Balanced funds have been a bad bet.

Advertisement

Balanced funds have been a bad bet.

When you invest in a balanced fund, you expect its manager to add value to your portfolio. In particular, you expect the manager to allocate your money among stocks, bonds and cash based upon the condition of the market. Nimble asset allocation should help to minimize your losses during bear markets and maximize your gains during bull market — at least in theory.

The past year has provided an ideal test to see whether the balanced approach works in reality as well as in theory. By tracking how balanced funds weathered the recent ups and downs, we can asses whether they actually added value. Did their managers boost returns and reduce risk by adjusting their portfolios? Were these managers good at predicting which way the market would move next?

To find out, I examined the portfolio allocation of the largest 15 balanced funds in Canada that disclose this information. The funds that I scrutinized account for more than 44% of the $84 billion that Canadians have invested in balanced funds. Among them, these 15 funds reap close to $1 billion in management fees each year.

I compared the portfolios of the 15 funds at two points — the second quarter of 2008 versus the first quarter of 2009. The former was when Canadian equity values were peaking, right before the crash. The latter was when stocks were bottoming and getting ready to stage a 50% rally.

If balanced funds could have foreseen the future, they would have lightened up on stocks at the peak of the bull market and then jumped back into stocks before the recent low. This is presumably what you’re paying a balanced fund to do.

But it’s not at all what happened. The managers of these funds appear to have been asleep at the wheel. In fact, the data strongly suggest that balanced fund managers added hardly any value during the crisis. Contrary to public perception, those managers did not actively manage their asset allocation by moving from one investment category to another based on market factors. As you can see in Asleep at the wheel below, these fund managers barely budged their asset allocation, either at the recent peak or at the recent low.

The balanced funds that I examined seem to follow a very simple strategy. They stick to a stable asset allocation regardless of market direction. For example, if a balanced fund has decided that the best asset allocation is 45% stocks and 55% bonds and cash, it keeps to this split regardless of what happens in the market. If stocks plunge in price, reducing the value of the stocks below 45% of the fund’s total, the fund buys more stocks to bring its exposure back to 45% (and vice versa).

In general, there is nothing wrong with keeping to a fixed asset allocation. The strategy works because it forces you to add stocks when prices drop. It prods you in the opposite direction when stocks get expensive. In that case, a fixed allocation forces you to sell some of those overpriced stocks and buy bonds instead.

But you do not need to pay a balanced fund more than 2% a year in management fees to do something that anyone with a tad of discipline can do more cheaply.

Let’s imagine that five years ago you had placed 45% of your money in a low-cost equity index fund, 35% in a bond index fund, and the remainder in cash. Assume you rebalanced once a year to keep to those proportions. Following this simple strategy, you would have achieved an average annual return of roughly 5.1% and beat 90% of balanced funds. Not only that, but your bear market losses between June 2008 and February 2009 would have been around 18%, versus an average loss of 23.5% for balanced funds.

No magic is involved in these results. The returns from a do-it-yourself strategy are nearly sure to be better than the typical balanced fund because of your much lower fees. A typical balanced fund holds more than 50% of its portfolio in bonds and cash — two types of assets that require little if any active management. Problem is, a balanced fund still charges full management fees on those assets. In fact, you’re paying the manager to hold cash for you, which is truly senseless!

A big slice of the 2.4% or so that you pay in management fees on a typical balanced fund is wasted. Even if you’re a fan of active management, you could cut your fees by a third simply by investing in an actively managed fund for the stock component of your portfolio, buying a low-cost bond fund or an ETF for the fixed-income portion of your portfolio, and holding your cash in a high-interest bank account or money market fund.

My research indicates that only two balanced funds deserve recognition in terms of both minimizing losses and maximizing returns. The BMO Asset Allocation Fund and the RBC Monthly Income Fund (series F) outperformed the index portfolio on three important benchmarks — the extent of their bear market losses, the magnitude of their subsequent recovery between March and June of this year, and their five-year average returns.

You should give these two funds a look if you’re set on buying a balanced fund. Or you may simply decide to save money and allocate your assets on your own. One advantage of this do-it-yourself approach is that it allows you to choose an asset allocation formula that suits your personal circumstances, rather than the one-size-fits-all approach of a balanced fund.

Some people use fancy computer models to decide on a suitable asset allocation. I think a better approach is to avoid putting yourself in a situation where the worst case leaves you in a situation that is too horrible to contemplate.

Your experience during the recent market turmoil should determine your asset allocation going ahead. If you lost sleep, or couldn’t eat, at the very bottom of the bear market this past year, you should never put yourself in that position again. Never mind probabilities and standard deviations. If you are not prepared to face another 20% loss in the future, do not keep 45% of your investment in equities.

Worst cases (left) summarizes the losses that you would have suffered with different mixes of stocks and bonds during the meltdown. Let those losses be your starting point for deciding on your future asset allocation. If you want to make sure that your portfolio is not going to go down by more than 15%, you should not hold more than 40% of your money in stocks.

I acknowledge that the losses of the past year were a rare occurrence and are not likely to be repeated. But if events do surprise and you lose half of your retirement money, it’s no comfort to tell yourself that you were hit by a low probability event. Far better to plan your portfolio so you never have to face that possibility.

When you invest in a balanced fund, you expect its manager to add value to your portfolio. In particular, you expect the manager to allocate your money among stocks, bonds and cash based upon the condition of the market. Nimble asset allocation should help to minimize your losses during bear markets and maximize your gains during bull market — at least in theory.

The past year has provided an ideal test to see whether the balanced approach works in reality as well as in theory. By tracking how balanced funds weathered the recent ups and downs, we can asses whether they actually added value. Did their managers boost returns and reduce risk by adjusting their portfolios? Were these managers good at predicting which way the market would move next?

To find out, I examined the portfolio allocation of the largest 15 balanced funds in Canada that disclose this information. The funds that I scrutinized account for more than 44% of the $84 billion that Canadians have invested in balanced funds. Among them, these 15 funds reap close to $1 billion in management fees each year.

I compared the portfolios of the 15 funds at two points — the second quarter of 2008 versus the first quarter of 2009. The former was when Canadian equity values were peaking, right before the crash. The latter was when stocks were bottoming and getting ready to stage a 50% rally.

If balanced funds could have foreseen the future, they would have lightened up on stocks at the peak of the bull market and then jumped back into stocks before the recent low. This is presumably what you’re paying a balanced fund to do.

But it’s not at all what happened. The managers of these funds appear to have been asleep at the wheel. In fact, the data strongly suggest that balanced fund managers added hardly any value during the crisis. Contrary to public perception, those managers did not actively manage their asset allocation by moving from one investment category to another based on market factors. As you can see in Asleep at the wheel below, these fund managers barely budged their asset allocation, either at the recent peak or at the recent low.

The balanced funds that I examined seem to follow a very simple strategy. They stick to a stable asset allocation regardless of market direction. For example, if a balanced fund has decided that the best asset allocation is 45% stocks and 55% bonds and cash, it keeps to this split regardless of what happens in the market. If stocks plunge in price, reducing the value of the stocks below 45% of the fund’s total, the fund buys more stocks to bring its exposure back to 45% (and vice versa).

In general, there is nothing wrong with keeping to a fixed asset allocation. The strategy works because it forces you to add stocks when prices drop. It prods you in the opposite direction when stocks get expensive. In that case, a fixed allocation forces you to sell some of those overpriced stocks and buy bonds instead.

But you do not need to pay a balanced fund more than 2% a year in management fees to do something that anyone with a tad of discipline can do more cheaply.

Let’s imagine that five years ago you had placed 45% of your money in a low-cost equity index fund, 35% in a bond index fund, and the remainder in cash. Assume you rebalanced once a year to keep to those proportions. Following this simple strategy, you would have achieved an average annual return of roughly 5.1% and beat 90% of balanced funds. Not only that, but your bear market losses between June 2008 and February 2009 would have been around 18%, versus an average loss of 23.5% for balanced funds.

No magic is involved in these results. The returns from a do-it-yourself strategy are nearly sure to be better than the typical balanced fund because of your much lower fees. A typical balanced fund holds more than 50% of its portfolio in bonds and cash — two types of assets that require little if any active management. Problem is, a balanced fund still charges full management fees on those assets. In fact, you’re paying the manager to hold cash for you, which is truly senseless!

A big slice of the 2.4% or so that you pay in management fees on a typical balanced fund is wasted. Even if you’re a fan of active management, you could cut your fees by a third simply by investing in an actively managed fund for the stock component of your portfolio, buying a low-cost bond fund or an ETF for the fixed-income portion of your portfolio, and holding your cash in a high-interest bank account or money market fund.

My research indicates that only two balanced funds deserve recognition in terms of both minimizing losses and maximizing returns. The BMO Asset Allocation Fund and the RBC Monthly Income Fund (series F) outperformed the index portfolio on three important benchmarks — the extent of their bear market losses, the magnitude of their subsequent recovery between March and June of this year, and their five-year average returns.

You should give these two funds a look if you’re set on buying a balanced fund. Or you may simply decide to save money and allocate your assets on your own. One advantage of this do-it-yourself approach is that it allows you to choose an asset allocation formula that suits your personal circumstances, rather than the one-size-fits-all approach of a balanced fund.

Some people use fancy computer models to decide on a suitable asset allocation. I think a better approach is to avoid putting yourself in a situation where the worst case leaves you in a situation that is too horrible to contemplate.

Your experience during the recent market turmoil should determine your asset allocation going ahead. If you lost sleep, or couldn’t eat, at the very bottom of the bear market this past year, you should never put yourself in that position again. Never mind probabilities and standard deviations. If you are not prepared to face another 20% loss in the future, do not keep 45% of your investment in equities.

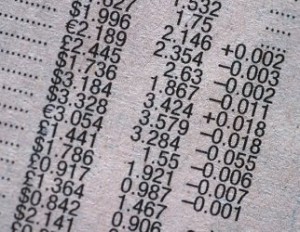

Worst cases (left) summarizes the losses that you would have suffered with different mixes of stocks and bonds during the meltdown. Let those losses be your starting point for deciding on your future asset allocation. If you want to make sure that your portfolio is not going to go down by more than 15%, you should not hold more than 40% of your money in stocks.

I acknowledge that the losses of the past year were a rare occurrence and are not likely to be repeated. But if events do surprise and you lose half of your retirement money, it’s no comfort to tell yourself that you were hit by a low probability event. Far better to plan your portfolio so you never have to face that possibility.

| Allocation | Stocks | Government bonds | Corporate bonds | Cash or equivalent | Other |

| 2nd quarter of 2008 | 46.7% | 20.6% | 13.3% | 15.2% | 4.2% |

| 1st quarter of 2009 | 46.2% | 20.7% | 15.2% | 15.3% | 2.6% |

| Source: Fundata Canada Inc. and FundScope Ltd. | |||||

| Allocation | Losses between June 2008 and February 2009 | |

| 100% equity | 43% | |

| 70% equity/30% bonds and cash | 29% | |

| 60% equity/40% bonds and cash | 25% | |

| 50% equity/50% bonds and cash | 20% | |

| 40% equtiy.60% bonds and cash | 15% | |

| Source: Fundata Canada Inc. and FundScope Ltd. | ||

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

I am glad to be a visitor of this everlasting web site, regards for this rare info!