The enemy in the mirror

You can double your investment returns with a one-two punch. One, understand how the market really works. And two, realize how your own actions are working against you

Advertisement

You can double your investment returns with a one-two punch. One, understand how the market really works. And two, realize how your own actions are working against you

My brother Ian is a huge fan of the 1999 movie Fight Club, particularly the scene where the lead character Tyler, played by Edward Norton, is shown throwing haymaker punches at his own, swollen face. Norton’s character is metaphorically battling his materialistic urges. Most investors fight similar battles in a war against themselves.

Much of that internal grappling comes from misunderstanding how the stock market really works. Couple that misunderstanding with our race to become rich, and we do everything wrong. We buy when our mutual funds are soaring, then we sell them or cease adding to them when they slump. We give up much of our gains to pricey fund managers, even though after fees, their funds trail the performance of cheaper investing options such as index funds. We’re confident we can predict where the market is going, though even the professionals have a terrible track record when it comes to forecasting the market’s ups and downs. In short, our greed and confidence can work against us, keeping us from realizing our true investing potential.

I can’t promise to collar your inner doppelganger, but I can help you understand how the stock market works—and how human emotions can sabotage the best-laid plans. Once you understand how your own all-too-human behaviour is affecting your investing, you’ll experience greater financial success.

When a 10% gain isn’t a 10% gain

Imagine a mutual fund that has averaged 10% a year over the past 20 years, after all fees and expenses. Some years, it might have lost money; other years it might have profited beyond expectation. It’s a roller coaster ride, right? But imagine, on average, that it gained 10% annually through all the bumps, rises, twists, and turns. If you found a thousand investors who had invested in that fund from 1990 to 2010, you would expect that each would have netted a 10% annual return.

But on average, they wouldn’t have made anything close to that, because most investors shoot themselves in the foot. When the fund has a couple of bad years, too many investors react by putting less money in the fund, or stopping their contributions entirely. They’re often prompted by their investment advisers, who say, “This fund hasn’t been doing well lately. Because we’re looking after your best interests, we’re going to move your money to another fund that is doing better at the moment.” And when the fund has a great year, most individual investors and financial advisers scramble to put more money in the fund, like feral cats around a fat salmon.

This behaviour is self-destructive. Investors sell or cease to buy after the fund has become cheap, and they buy like lunatics when the fund becomes expensive. If there weren’t so many people doing it, we would call it a “disorder” and name it after some dead Teutonic psychologist. This kind of behaviour ensures that investors will pay higher-than-average prices for their funds over time. Whether it’s an index fund or an actively managed mutual fund, most investors perform far worse than the funds they own—because they like to buy high, and they hate buying low. That’s a pity. And it can make the difference between retiring early and not retiring at all.

John Bogle, the founder of U.S. investment management giant The Vanguard Group, describes in his 2007 book, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, that the average actively managed U.S. mutual fund reported a 10% annual gain from 1980 to 2005 after fees and expenses, but investors in those funds averaged just 7.3% over the same period. Their fear of low prices prevented them from buying when the funds were low, while their elation at high prices encouraged purchases when fund prices were high. Such bizarre behaviour has devastating financial consequences, as investors give away 2.7% annually because of their knee-jerking alter egos.

As this example shows, over a 25-year period, that’s a pretty expensive habit:

$50,000 invested at 10% a year for 25 years = $541,735.29

$50,000 invested at 7.3% a year for 25 years = $291,046.95

Cost of irrationality = $250,688.34

But what if you didn’t care what the stock market was doing?

As investors, you really don’t have to watch the stock market to see if it’s going up or down. In fact, if you bought an index fund for 25 years, with an equal dollar amount going into that fund each month (called “dollar-cost averaging”) and if that fund averaged 10% annually, you would have averaged 10% or more. Why more? If you put a regular $100 a month into a fund, that $100 would have bought fewer units of that fund when prices were high, but it would have bought more units of that fund when prices were lower.

Most investors don’t do that—they exhibit nutty behaviour

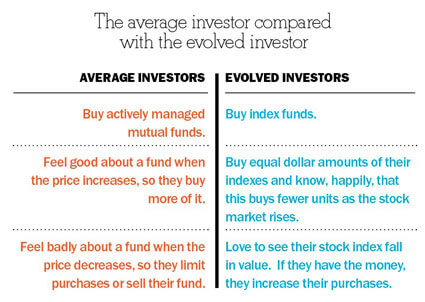

Combine the crazy behaviour of the average investor with the fees associated with actively managed mutual funds, and the average investor ends up with a puny portfolio compared with the disciplined investor, who puts in the same amount of money into index funds every month. The following table categorizes the behaviour of the two types of investors, assuming both will be working—and adding to their investments—for at least the next five years.

I’m not going to suggest that all index investors are evolved enough to ignore the market’s fearful roller coaster, while shunning the self-sabotage caused by fear and greed. But if you can learn to invest regularly in index funds and remain calm when the markets fly upward or downward, you’ll grow far wealthier. Below, you can see examples, based on actual U.S. returns between 1980 and 2005.

The figure on the left side ($84,909.01) is probably generous. The 10% annual return for the average actively managed fund has been historically overstated because it doesn’t include sales charges, adviser wrap fees, or the added liability of taxes in a non-registered account.

Disciplined index investors who don’t sabotage their accounts can end up with a portfolio that’s easily twice as large as that of the average investor over a 25-year period.

Small details like these can allow people with middle-class incomes to amass wealth more effectively than their high salaried neighbours—especially if the middle-class earners think twice about spending more than they can afford. Even if your neighbours invest twice as much as you each month, if they are average, they will buy actively managed mutual funds, and they will either chase hot performers or fail to stay committed to their investments when the markets fall. They’ll feel good about buying into the markets when they’re expensive, and they won’t be as keen to buy when they’re on sale.

I don’t want you to be like your neighbour. Avoid that kind of self-destructive behaviour and you’ll build more wealth.

It’s not timing the market that matters; it’s time in the market

There are smart people (and people who aren’t so smart) who mistakenly think they can jump in and out of the stock market at opportune moments. It seems simple. Get in before the market rises and get out before it drops. This is referred to as “market timing.” But most financial advisers have a better chance beating Roger Federer in a tennis match than effectively timing the market for your account.

Vanguard’s Bogle, who was named by Fortune magazine as one of the four investment giants of the 20th century, has this to say about market timing:

“After nearly 50 years in this business, I do not know of anybody who has done it successfully and consistently. I don’t even know anybody who knows anybody who has done it successfully and consistently.”

When the markets go raving mad, jumping in and out can be tempting. But stock markets are highly irrational, and characterized by short-term swings. The stock market will often fly higher than most people expect during a euphoric phase, while plunging further than anticipated during times of economic duress.

Doing nothing but regularly putting money into an index fund might sound boring during a financial boom, and it might sound terrifying during a financial meltdown. But the vast majority of people (including professionals) who try jumping in and out of the stock market allow their emotional judgments to hurt their profits, as they often end up buying high and selling low.

What can you miss by guessing wrong?

Studies show that most market moves are like the flu you got last year, or the mysterious $10 bill you found in the pocket of your jeans. In each case, you don’t see it coming. Even when looking back at the stock market’s biggest historical returns, Jeremy Siegel, author of Stocks for the Long Run and professor of business at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, suggests that there’s no rhyme or reason when it comes to market activity. He looked back at the biggest stock market moves since 1885 (focusing on trading sessions where the markets moved by 5% or more in a single day) and tried connecting each of them to a world event.

Seventy-five percent of the time, he couldn’t find logical explanations for such large stock market movements—and he had the luxury of looking back in time, and trying to match the market’s behaviour with historical world news. If a smart man like Siegel can’t make connections between world events and the stock market’s movements with the benefit of hindsight, then how is someone supposed to predict future movements based on economic events—or the prediction of events to come? It’s as improbable as guessing which of the moths frantically flying around your light bulb is going to be fried first.

If anyone ever convinces you to act on their short-term stock market prediction, it could end up being a very expensive mistake. Let’s look at the U.S. stock market from 1982 through December 2005 as an example.

During this time, the stock market averaged 10.6% annually. But if you didn’t have money in the stock market during the 10 best trading days, your average return would have dropped to 8.1%. If you missed the best 50 trading days, your average return would have been just 1.8%. Markets can move so unpredictably, and so quickly. If you take money out of the stock market for a day, a week, a month, or a year, you could miss the best trading days of the decade. You’ll never see them coming. They just happen. More importantly, as I said before, neither you nor your broker is going to be able to predict them.

Legendary investor and self-made billionaire Kenneth Fisher, who writes a column in Forbes magazine, had this to say, about market timing:

“Never forget how fast a market moves. Your annual return can come from just a few big moves. Do you know which days those will be? I sure don’t and I’ve been managing money for a third of a century.”

The easiest way to build a responsible, diversified, investment account is to invest regularly with stock and bond index funds. Many people view bonds as boring because they don’t produce the same kind of long-term returns that stocks do. But they don’t fall like stocks are apt to do either. They’re the steadier, slower, more dependable part of an investment portfolio. A responsible portfolio has a percentage allocated to the stock market and a percentage allocated to the bond market, with an increasing emphasis on bonds as the investor ages.

But when stocks start racing upward and everyone’s getting giddy on the profits they’re making, most people ignore their bonds (if they own any at all) and buy more stocks. Many financial advisers fall prey to the same weakness. But those ignoring their planned allocations between stocks and bonds set themselves up for disaster.

How can you ensure that you’re never a victim? It’s far easier than you might think. If you understand exactly what stocks are—and what you can expect from them—you’ll fortify your odds of success.

On stocks: What you really should have learned in school

The stock market is a collection of businesses. It isn’t just a squiggly bunch of lines on a chart or quotes in the newspaper. When you own shares in an equity index fund, you own something that’s as real as the land you’re standing on. You become an indirect owner of all kinds of industries and businesses, via the companies you own within your fund: land, buildings, brand names, machinery, transportation systems, and products, to name a few. Just understanding this key concept can give you a huge advantage as an investor.

Business earnings and stock price growth are two separate things, but over the long term they tend to reflect the same result. For example, if a business grew its profits by 1,000% over a 30-year period, we could expect the stock price of that business to appreciate similarly over the same period.

It’s the same for a stock market index. If the average company within an index grew by 1,000% over 30 years (that’s 8.32% annually) we could expect the stock market index to perform similarly. Long term, stock markets predictably reflect the fortunes of the businesses. But over shorter time periods, the stock market can be as irrational as a crazy dog on a leash. And it’s the crazy dog’s movements that can—if we let them—lure us closer to poverty than to wealth.

The stock market is a dog on a leash

When I took her for extended runs in open fields, she was able to burn off some octane. I would run in a single direction while she darted upward, backward, right, then left. But collared by a very long rope, she couldn’t escape.

If I ran from the lake to the barn with Sue on a leash, and if it took me 10 minutes to get there, then any observer would realize it would take the dog 10 minutes to get there as well. True, the dog could bolt ahead or lag behind while sticking its nose in a gift left behind by another canine. But ultimately, she couldn’t cover the distance much slower or much faster than I did—because of the leash.

Now imagine a bunch of emotional gamblers who watch and bet money on leashed dogs. When a dog bursts ahead of its owner, the gamblers put money on that dog, betting that it will sprint far off into the distance. But the dog’s on a leash, so eventually it’s destined to either slow down or stop while the owner catches up.

But the gamblers don’t think about that. They ignore the leash and place presumptuous bets assuming that the dog will maintain its frenetic pace. Their greed wraps itself around their brains and squeezes. Without that cranial compression, they would see that the leashed dog couldn’t outpace its owner.

It sounds so obvious, doesn’t it? Now get this: the stock market is exactly like a dog on a leash. If the stock market races at twice the pace of business earnings for a few years, then it has to either wait for business earnings to catch up, or it will get choke-chained back in a hurry. But a rapidly rising stock market can cause people to forget that reality: they pile larger and larger sums into stocks with delusional confidence. I’ll use an individual stock to prove the point.

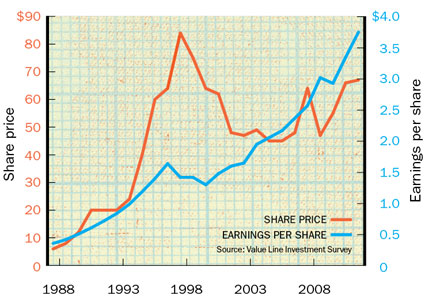

Coca-Cola bounds from its owner

From 1988 to 1998, the Coca-Cola Company increased its profits by 294%. During this short period (and yes, 10 years is a stock market blip) Coca-Cola’s stock price increased by 966%. Because it was rising rapidly, investors—including mutual fund managers—fell over themselves to buy Coca-Cola shares, pushing the share price even higher. Greed might be the greatest hallucinogenic known to humanity.

The dog (Coca-Cola’s stock) was racing ahead of its master (Coca-Cola’s business earnings). A rational share price increase must be in line with profits. If Coca-Cola’s business earnings increased by 294% from 1988 to 1998, we would assume that its stock price would grow by a percentage that was at least similar, maybe a little higher, and maybe a little lower. But Coca-Cola’s stock price growth of 966% was irrational.

Coca-Cola’s stock price vs. Coca-Cola’s earnings

Can you see what happened to the blazing Coca-Cola share price (in dark blue) when it got far ahead of Coca-Cola’s business profits (in light blue)? The dog eventually dropped back to meet its owner. After blazing ahead at 29% a year for a decade (from 1988 to 1998) Coca-Cola’s stock price eventually “heeled.” It had to. You can see in the chart that the stock price was lower in 2011 than it was in 1998. But, during the past 21 years, when were most people drunkenly pouring money into Coca-Cola shares? In the late 1990s. Why? Because the stock had been “performing well.” And most of those investors haven’t made a penny in profits over the last dozen years. Too many of them either sold or shunned the shares when the stock became cheaper in 2003 and 2004.

Ironically, a $10,000 investment in Coca-Cola stock in 1990 would have been worth nearly $100,000 by early 2011 (in U.S. dollars) with reinvested dividends. That’s an annualized return of about 11.5%. But few Coca-Cola shareholders earned anything close to that because of their giddy preference for rising prices and their fear of discounts.

I’m not suggesting that you should run out and buy Coca-Cola shares. What I am suggesting is that whether people invest in index funds, actively managed mutual funds or individual stocks, most investors significantly underperform the investment products they own. If you can defeat that enemy in the mirror by investing regular monthly sums—or by increasing your contributions when the markets fall—you can make twice as much money as your neighbour, even if you own the exact same investments.

Excerpted with permission of the publisher John Wiley & Sons, Inc., from Millionaire Teacher: The Nine Rules of Wealth You Should Have Learned in School by Andrew Hallam. Copyright © 2011 by John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte. Ltd. This book is available at all bookstores, online booksellers and from the Wiley website at www.wiley.ca or call 1-800-567-4797. More information at facebook.com/millionaireteacher.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email