The payoff: Reaching true wealth

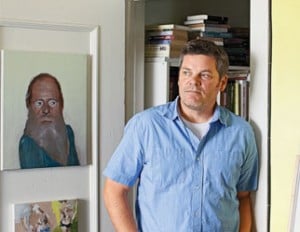

This University of Toronto philosophy professor writes about reaching "true wealth" and what it took to get him there

Advertisement

This University of Toronto philosophy professor writes about reaching "true wealth" and what it took to get him there

I was the sort of kid who maintained a substantial cache of carefully catalogued Halloween candy into early December, by which time I had finished my Christmas shopping. I know, sad. But this combination of thrift and micromanagement, bequeathed to me by my blue-collar grandparents and a control-freak mother, has proved helpful in my chosen career of professional philosopher.

The minimum qualification for this strange job, the Ph.D. degree, requires at least eight and usually more like 12 years of post-secondary study. It’s a long haul in every sense. As Stephen Leacock said, “The meaning of this degree is that the recipient of instruction is examined for the last time in his life, and pronounced completely full. After this, no new ideas can be imparted to him.” We should add, these days, that no bank or agency will lend him another dime.

I learned all I needed to know about money in grad school. Like most grad students, I was poor both in relative terms (most of my friends had jobs and were earning money, buying houses) and absolute ones (no savings, no restaurant meals, no new clothes, a hand-me-down TV). I never valued the small luxuries of life—a bottle of wine, a hardcover novel bought on a whim, a concert ticket—more than when I coul-dn’t afford them.

I was 28 years old when I fin-ished my Ph.D. With a combination of frugal living and scholarships I had narrowly avoided the debt that cripples so many graduates. But then as now the academic career market was a shambles. I had no job and not much prospect of one. (It was 1991; the economy was in yet another post-recession slump.) There were lean years to come, stitching together contract work here and a freelance cheque there. I went through all the usual contortions of the semi-employed academic. Go to law school? Commit to journalism? Apply for the foreign service? (I actually did that one, got as far as a job offer, and then balked.)

When I finally landed a secure job, in 1998, I was 35 and it was too late to save my marriage. My wife was an academic too, deep in her own Ph.D., but with somewhat extravagant tastes—a fatal combination. We split the meagre amounts on our asset lists and went our separate ways.

They say true wealth resides in never having to worry about money. Or, according to the Micawber Principle, from Dickens’s Great Expectations: “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

Which is of course why a majority of millionaires still report that they “feel poor.” When I was researching a book about the nature of happiness, I kept coming across different versions of this statistical result. Most people, no matter what their net worth, believe that they will be happy with just a little more, usually around 10%. The psychology should be clear: 10% represents an improvement within reach, but also sufficient to leverage a meaningful difference. It’s the monetary equivalent of the 10 or 15 pounds most people figure they ought to lose in order to feel good about themselves.

The catch is that the 10% income bump is like the horizon: it forever recedes even as you approach it. The ancient Greek philosophers didn’t need psychology or statistics to see the trap. There is, they tell us, a human vice called pleonexia, their term for that familiar double bind whereby the more you have, the more you want. Pleonexia is more than mere greed; it is a kind of intrapsychic race to the bottom. Each gain in material advantage generates within the soul a new deficit in happiness. Hence the need to seek a further gain. And so on, ad infinitum.

There are lots of different views on how to halt this downward spiral. You can tamp down your desires, detach yourself from the world of getting and spending, or sever all connections to material things. As the old Shaker hymn has it, “ ’Tis a gift to be simple.”

But there are also other balms to the over-excited soul than asceticism. Now that I can afford simple luxuries and, now and then, extravagant ones, I find solace in collecting art—sketches and studies, mostly, rather than full pieces beyond my means. It’s the only purchasable thing I know whose essence transcends price. No matter what you pay for it, its value remains incalculable.

And yes, I hoard and catalogue the art just like I did the Halloween candy. The great thing is that the collection never gets smaller, and the happiness is never in deficit, no matter how much I indulge myself. Now that’s a gift that keeps on giving.

Mark Kingwell is a professor in philosophy at the University of Toronto and the author of 16 books including The Wage-Slave’s Glossary (Biblioasis).

I was the sort of kid who maintained a substantial cache of carefully catalogued Halloween candy into early December, by which time I had finished my Christmas shopping. I know, sad. But this combination of thrift and micromanagement, bequeathed to me by my blue-collar grandparents and a control-freak mother, has proved helpful in my chosen career of professional philosopher.

The minimum qualification for this strange job, the Ph.D. degree, requires at least eight and usually more like 12 years of post-secondary study. It’s a long haul in every sense. As Stephen Leacock said, “The meaning of this degree is that the recipient of instruction is examined for the last time in his life, and pronounced completely full. After this, no new ideas can be imparted to him.” We should add, these days, that no bank or agency will lend him another dime.

I learned all I needed to know about money in grad school. Like most grad students, I was poor both in relative terms (most of my friends had jobs and were earning money, buying houses) and absolute ones (no savings, no restaurant meals, no new clothes, a hand-me-down TV). I never valued the small luxuries of life—a bottle of wine, a hardcover novel bought on a whim, a concert ticket—more than when I coul-dn’t afford them.

I was 28 years old when I fin-ished my Ph.D. With a combination of frugal living and scholarships I had narrowly avoided the debt that cripples so many graduates. But then as now the academic career market was a shambles. I had no job and not much prospect of one. (It was 1991; the economy was in yet another post-recession slump.) There were lean years to come, stitching together contract work here and a freelance cheque there. I went through all the usual contortions of the semi-employed academic. Go to law school? Commit to journalism? Apply for the foreign service? (I actually did that one, got as far as a job offer, and then balked.)

When I finally landed a secure job, in 1998, I was 35 and it was too late to save my marriage. My wife was an academic too, deep in her own Ph.D., but with somewhat extravagant tastes—a fatal combination. We split the meagre amounts on our asset lists and went our separate ways.

They say true wealth resides in never having to worry about money. Or, according to the Micawber Principle, from Dickens’s Great Expectations: “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

Which is of course why a majority of millionaires still report that they “feel poor.” When I was researching a book about the nature of happiness, I kept coming across different versions of this statistical result. Most people, no matter what their net worth, believe that they will be happy with just a little more, usually around 10%. The psychology should be clear: 10% represents an improvement within reach, but also sufficient to leverage a meaningful difference. It’s the monetary equivalent of the 10 or 15 pounds most people figure they ought to lose in order to feel good about themselves.

The catch is that the 10% income bump is like the horizon: it forever recedes even as you approach it. The ancient Greek philosophers didn’t need psychology or statistics to see the trap. There is, they tell us, a human vice called pleonexia, their term for that familiar double bind whereby the more you have, the more you want. Pleonexia is more than mere greed; it is a kind of intrapsychic race to the bottom. Each gain in material advantage generates within the soul a new deficit in happiness. Hence the need to seek a further gain. And so on, ad infinitum.

There are lots of different views on how to halt this downward spiral. You can tamp down your desires, detach yourself from the world of getting and spending, or sever all connections to material things. As the old Shaker hymn has it, “ ’Tis a gift to be simple.”

But there are also other balms to the over-excited soul than asceticism. Now that I can afford simple luxuries and, now and then, extravagant ones, I find solace in collecting art—sketches and studies, mostly, rather than full pieces beyond my means. It’s the only purchasable thing I know whose essence transcends price. No matter what you pay for it, its value remains incalculable.

And yes, I hoard and catalogue the art just like I did the Halloween candy. The great thing is that the collection never gets smaller, and the happiness is never in deficit, no matter how much I indulge myself. Now that’s a gift that keeps on giving.

Mark Kingwell is a professor in philosophy at the University of Toronto and the author of 16 books including The Wage-Slave’s Glossary (Biblioasis).

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email