A better way to generate retirement income

Think you need to buy high-yield investments when drawing down your portfolio? A total-return approach can mean less risk and lower taxes while still providing the cash flow you need

Advertisement

Think you need to buy high-yield investments when drawing down your portfolio? A total-return approach can mean less risk and lower taxes while still providing the cash flow you need

![Portfolio_Builder_banner_1256X300[2][2][2]](https://www.moneysense.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Portfolio_Builder_banner_1256X300222.jpeg)

Retirement brings many life changes, and it’s not just about more time to golf, travel and hang out with the grandkids. Once you’re no longer earning employment income you’ll start relying on your investments to generate cash flow. That means changing the way you manage your portfolio.

But just because you’ll be making withdrawals doesn’t mean you need to make a fundamental shift in your investment strategy. This idea often worries investors who use exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or mutual funds for their stock holdings. They may believe these “growth-oriented” funds are no longer appropriate and feel they should switch to dividend funds, or even individual dividend stocks when they retire. Others look to replace traditional fixed-income funds with high-yield bonds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), or even more exotic income strategies such as writing call options.

The concern is understandable: after all those years of adding money to the portfolio, it seems only natural to change gears once you start taking it out. Retirees need a steady stream of income they can live on, and dividend stocks, REITs and high-yield bonds seem like the logical choice. Some experienced investors can indeed build diversified, tax-efficient portfolios by focusing on income-oriented investments like these. But if you’re more comfortable using broad-market funds, you shouldn’t feel the need to change your whole strategy in retirement. Your portfolio can still generate reliable cash flow even if it isn’t filled with holdings chosen for their large payouts.

In fact, if you’re making investment choices based primarily on yield you might be ignoring other important factors, such as risk and taxes. That’s why experienced portfolio managers often use a more sophisticated approach. Because it relies on all types of investment growth (dividends, interest and realized capital gains) it’s often called a “total return” strategy.

To understand this approach, it’s helpful to make a distinction between income and cash flow. The former term refers to cash distributions paid by stocks, bonds or funds: that primarily means dividends and interest, but it also includes return of capital, which we’ll discuss in a moment. Cash flow, by contrast, includes not only distributions but also the proceeds from selling investments in the portfolio.

While many retired people say they need income from their nest egg, it’s more accurate to say they need cash flow. After all, if you rely on your portfolio to cover $2,000 a month in expenses, it makes no difference whether those dollars come from dividends, interest or realized capital gains.

Granted, it would be ideal to live off just the dividends and interest from your portfolio, because if you never have to eat into your capital by selling investments, you’ll never run out of money. Unfortunately, only the wealthiest can afford to do that. Gone are the days when you could buy guaranteed investment certificates, (GIC) and government bonds yielding a safe and reliable 6%, allowing you to leave the principal untouched. Today high-quality bonds and GICs typically pay less than 2.5%, while a diversified basket of stocks might generate 3% in dividends (the broad Canadian and U.S. indexes actually yield considerably less). That means a balanced portfolio would need to be well over a million bucks to generate a modest $30,000 in annual income—and that’s before taxes and fees. The reality is that most investors will have to draw down some of their capital to meet their spending needs in retirement.

Wait, you say, it’s not necessary to settle for a paltry 2.5% or 3% income. You can select high-dividend stocks that yield 4% or more, or use high-yield bonds and REITs with payouts of 5% to 7%. But reaching for yield is problematic for at least three reasons.

No one is suggesting it’s impossible to build a well-diversified portfolio of dividend stocks. But it’s difficult, especially if you focus on Canadian companies. Some economic sectors (such as health care and technology) are barely present in Canada, and concentrating your portfolio in a few banks and energy stocks is riskier than many investors believe, even though it has worked well in recent years. The Canadian REIT sector is also tiny and dominated by just a few large names. Using low-cost index funds with hundreds or thousands of stocks offers far more diversification.

On the fixed-income side of the portfolio, high-yield bonds have big payouts for a reason: they’re much riskier than investment-grade bonds. They plunged along with stocks in 2008, for example, so they offered almost no safety net when you needed it most. High-quality government and corporate bonds have modest yields but they provide more ballast when stock markets are choppy.

While Canadian dividends are taxed favourably for low earners, that advantage disappears at higher incomes. In Ontario, for example, capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than Canadian dividends when your income is more than $83,237. Moreover, Canadian dividends must be “grossed up” by 38% on your tax return, so $1,000 in dividends counts as $1,380 of income. That can lead to clawbacks of your Old Age Security benefit.

High-yield U.S. and international stocks can be particularly tax-inefficient. Foreign dividends are taxable at your full marginal rate in the year they are received and may also be subject to withholding taxes (the U.S. skims off 15%), though these can often be recovered by claiming the foreign tax credit on your return.

REITs and high-yield bonds, meanwhile, throw off a lot of fully taxable income while offering little potential for growth, which makes them among the least tax-efficient of asset classes.

Capital gains, by contrast, are taxed at only half the rate of interest or foreign dividends, and you can defer them indefinitely so you’re only taxed when you sell the investment. That gives you a lot more flexibility. What’s more, you may be able to use a strategy called tax-loss selling to offset your gains with capital losses from other investments. Capital gains are also less likely to lead to Old Age Security clawbacks, since a $1,000 realized gain is considered only $500 of income.

Many income-oriented investors are attracted to ETFs and mutual funds with high payouts. But check the annual reports and you’ll discover that many of these funds rely heavily on “return of capital” or ROC. As the name suggests, ROC is a portion of your original investment that’s being returned to you in cash. This is widely misunderstood by investors who think they’re receiving a genuine return when the fund is really just taking money from one pocket and putting it in another.

Many popular “monthly income funds” boast payouts of 5% to 6% or more, but don’t make the mistake of believing that’s a guaranteed return. Consider a fund whose underlying stocks and bonds generate 3% in dividends and interest payments, which might be cut in half by the funds’ management fees. In that case, the fund would have to rely on capital gains or ROC to keep the payouts high. That would cause the fund’s value to steadily decline as it depletes its assets to artificially boost its yield.

Bottom line, when you focus on total return instead of yield, it’s easier to build a more broadly diversified, tax-efficient portfolio that balances growth and safety. And once you understand how to manage that portfolio in retirement, you can reliably generate the cash flow you need to meet your monthly expenses. Granted, this can be a little tricky, so an example will help.

On the next page, I’ll introduce you to Mindy, who will show you how to take advantage of the total return approach.

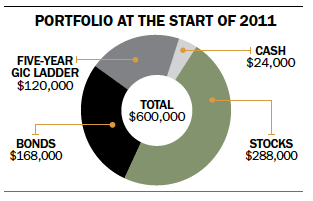

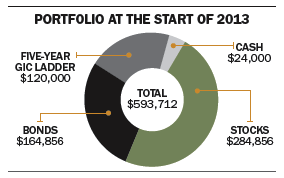

Meet Mindy, who has a non-registered portfolio worth $600,000 at the start of 2011. Mindy is a balanced investor whose target asset allocation is 50% stocks (made up of equal parts Canadian, U.S. and international equities) and 50% fixed income (bonds and GICs). She needs to draw $2,000 a month—or $24,000 annually—from her nest egg to meet her expenses. That’s 4% of the portfolio’s starting value, which should be a sustainable withdrawal rate.

Rather than selecting investments that will generate a 4% yield, Mindy uses three or four plain-vanilla ETFs and a five-year GIC ladder. Each GIC holds $24,000 to provide cash flow for the next five years. She also keeps $24,000 in a high-interest savings account, from which she makes a $2,000 withdrawal each month. Any dividends or interest from the stocks and bonds are simply reinvested in the funds.

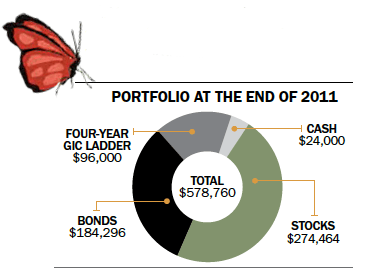

Now let’s look at how her portfolio would have evolved. Amid the European debt crises and political troubles in the U.S., stocks declined by 4.7% in 2011, while bonds climbed 9.7%. Meanwhile Mindy’s one-year GIC matured, providing $24,000 in cash to replenish the money she spent during the year. On New Year’s Eve her portfolio looks like this:

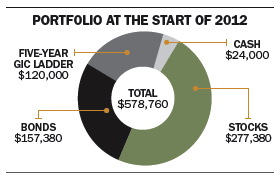

Once her hangover has worn off, Mindy knows it’s time to rebalance her portfolio, since it’s no longer 50% stocks and 50% fixed income. She also needs to buy a new five-year GIC to maintain the ladder. So she sells $24,000 of bonds and uses that money to buy the GIC. Then she sells another $2,916 worth of bonds and buys the same amount of stocks, bringing her back to her targets. Note that the total portfolio value remains unchanged:

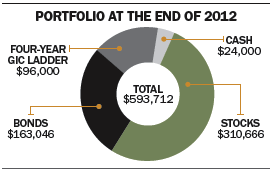

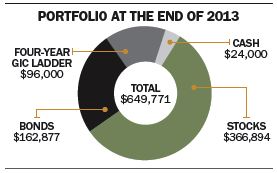

As it happens, 2012 is a fine year for investors, with stocks up 12% and bonds climbing 3.6%. Mindy spends the $24,000 in cash, but another GIC matures to replace it, so at the close of the year her portfolio looks like this:

At the end of 2011, Mindy replenished her GIC holdings and rebalanced by selling bonds, since stocks were down that year. But now she needs to put her portfolio back on track by selling $25,810 of stocks. She buys a new five-year GIC for $24,000 and puts the remaining $1,810 into bonds.

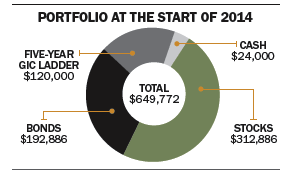

Interest rates spiked in the spring of 2013, and bonds had their first negative year since the 1990s. At the same time, stocks saw enormous gains: Mindy’s global equity holdings returned 28.8% as her portfolio reached a new high:

Once again, Mindy sells stocks to raise $24,000 for the new five-year GIC and $30,009 to top up her battered bond fund. She starts 2014 with this balanced portfolio:

And so on, and so on.

This approach has several benefits. First, it allows Mindy to use a small number of broadly diversified, low-cost ETFs rather than targeting individual stocks and bonds that will give her a 4% yield. This will reduce her risk and her taxes.

Second, it allows her a comfortable cushion in the event of a prolonged bear market. As we saw in 2011, Mindy had no need to let go of stocks at beaten-down prices, because she replenished her GIC ladder by selling bonds, which had an outstanding year. Even if a bear market is far more extreme (like 2008–09) or if it lasts two or three years (as it did after the dot-com bust) she can leave her stock holdings untouched, since the GICs would provide the cash flow she needs until stocks recover.

This is a simplified example. In the real world, managing a portfolio using a total return strategy can be quite complicated, since you’ll probably be dealing with multiple accounts, including RRIFs with mandatory taxable withdrawals. An experienced portfolio manager or retirement planner can help you manage the investments and keep your taxes to a minimum.

Dan Bortolotti is a consulting editor for MoneySense and an investment adviser with PWL Capital in Toronto.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

I’ve been re-reading this article every few years. Do you think this strategy still applies today? I’m always torn with the FIRE movement strategy of simply having 100% stocks across all markets and only drawings down 3-4% a year as needed vs this strategy you suggest.

Would love to see an answer to Philippe’s question.

One question I had myself though was, is the implication (given that an overall bad-year scenario was not discussed above) that given a few bad years on both the stock and bond markets, where together they didn’t even earn the required $24K annual spending budget, Mindy wouldn’t actually sell anything to buy a new 5y GIC and would let her GIC ladder simply decline to 4 and then 3 and then 2 and then 1 and then possibly even 0 years, waiting for enough of a bounce-back of either the stock or bond markets to replenish the GIC ladder?

IOW she is letting her 5y GIC ladder be her cushion against having to deplete her capital in the worst of times to do that? Or is she *always*, without fail replenishing the GIC ladder every year, no matter the cost to her stock and bonds capital?

I also keep this article bookmarked and re-read it every year or so (as I quickly approach my retirement years). It’s a great article – it puts an easy-to-understand process around a complex problem.

Brian’s question is exactly the same as what I had in mind. It would be great to hear a reply from the author or from other readers.

Thank you for being the voice of reason Dan. I hope all retirees read your new book as it is terrific. I just converted all my stocks to all in one ETF’s and I feel great! Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to you and your family.

I think that with the proliferation of one-fund ETFs that have emerged since this article was written, implementing this strategy would be very easy now. Have 5 years laddered GIC’s and the rest in the ETF of your choice