Time to rethink expectations

You might want to revise your plan, given the outlook for returns

Advertisement

You might want to revise your plan, given the outlook for returns

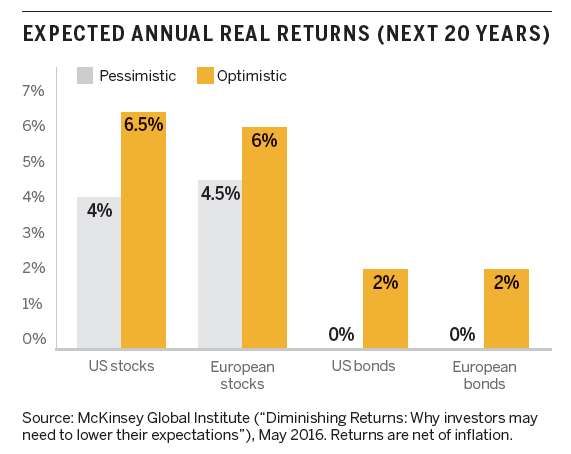

Returns on equities are impossible to predict, but the McKinsey researchers point to several factors that have changed since the “golden era,” including lower inflation, lower interest rates, slower economic growth and slimmer corporate profit margins due to greater competition. They suggest that over the next 20 years these trends could reduce real returns on stocks to between 4% and 5% a year. In a balanced portfolio you’re looking at an expected return of roughly 5% before inflation or about 3% in real terms.

It’s interesting to contrast this with newly updated guidelines from the Financial Planning Standards Council, which administers the Certified Financial Planner regime in Canada. (I hold this planning designation and pay dues to the FPSC.) Their guidelines for equities are similar to those in the McKinsey report, but their fixed-income expectations seem a tad optimistic. Assuming 2.1% inflation, the FPSC suggests that planners project returns of 4% for bonds and 3% for cash.

To be fair, planning guidelines are designed for long-term projections. If your retirement will last 30 years, it’s reasonable to assume average returns will be higher than their yields today. But the FPSC says its guidelines “are appropriate for making medium-term (5 to 10 years) and long-term (10+ years) financial projections.” In that context, it’s difficult to justify using 3% to 4% in a financial plan.

So how should investors adapt to lower expected returns? Too often the default decision is to tilt more towards stocks to compensate for the low yields on fixed income. That math makes sense, but the psychology doesn’t: Humans did not spontaneously become more risk-tolerant when bond yields fell below 2%. Couldn’t live with the volatility of a stock-heavy portfolio a decade ago? You certainly won’t be able to now.

Unfortunately, the solution is likely to be some combination of saving more, spending less or working longer than our parents did. We can also improve our outlook by keeping investment costs and taxes as low as possible, and by avoiding the seduction of strategies that promise market-beating returns with lower risk. No one wants to hear that, but let us be sure to remember that these factors—unlike future returns—are at least within our control.

Dan Bortolotti is contributing editor to MoneySense. Associate portfolio manager at PWL Capital (CFP, CIM)

Returns on equities are impossible to predict, but the McKinsey researchers point to several factors that have changed since the “golden era,” including lower inflation, lower interest rates, slower economic growth and slimmer corporate profit margins due to greater competition. They suggest that over the next 20 years these trends could reduce real returns on stocks to between 4% and 5% a year. In a balanced portfolio you’re looking at an expected return of roughly 5% before inflation or about 3% in real terms.

It’s interesting to contrast this with newly updated guidelines from the Financial Planning Standards Council, which administers the Certified Financial Planner regime in Canada. (I hold this planning designation and pay dues to the FPSC.) Their guidelines for equities are similar to those in the McKinsey report, but their fixed-income expectations seem a tad optimistic. Assuming 2.1% inflation, the FPSC suggests that planners project returns of 4% for bonds and 3% for cash.

To be fair, planning guidelines are designed for long-term projections. If your retirement will last 30 years, it’s reasonable to assume average returns will be higher than their yields today. But the FPSC says its guidelines “are appropriate for making medium-term (5 to 10 years) and long-term (10+ years) financial projections.” In that context, it’s difficult to justify using 3% to 4% in a financial plan.

So how should investors adapt to lower expected returns? Too often the default decision is to tilt more towards stocks to compensate for the low yields on fixed income. That math makes sense, but the psychology doesn’t: Humans did not spontaneously become more risk-tolerant when bond yields fell below 2%. Couldn’t live with the volatility of a stock-heavy portfolio a decade ago? You certainly won’t be able to now.

Unfortunately, the solution is likely to be some combination of saving more, spending less or working longer than our parents did. We can also improve our outlook by keeping investment costs and taxes as low as possible, and by avoiding the seduction of strategies that promise market-beating returns with lower risk. No one wants to hear that, but let us be sure to remember that these factors—unlike future returns—are at least within our control.

Dan Bortolotti is contributing editor to MoneySense. Associate portfolio manager at PWL Capital (CFP, CIM)

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email