How to make it to $1 million

It’s not easy, but for many middle-class Canadians it’s a realistic goal to save seven figures

Advertisement

It’s not easy, but for many middle-class Canadians it’s a realistic goal to save seven figures

Late last year, at the age of 56, Rick King found himself out of work. After some 30 years in sales and customer operations in the office equipment, telecom and energy sectors, King had become used to periods of unemployment. Over the years he’s received seven severance packages and has spent two year-long periods without a job. But when he received his latest buyout in November, King decided to leave the corporate world behind—at least for now. “I’m going to take a year to decide if I wanted to stay retired, and just explore new options,” he says. “I’m loving it.”

King can afford this luxury because he owns a paid-off home and has a seven-figure investment portfolio that’s generating enough income for himself, his wife Debbie and their 19-year-old daughter Sarah to live quite comfortably. King had some high-income years at the peak of his career, but his wealth is primarily the result of a lifelong commitment to frugality and saving, which he learned from his parents. His dad spent over 40 years in a lower management role at F.W. Woolworth and never earned more than $50,000 a year. His mother raised four kids, worked part-time at United Cigar Stores and managed the household finances. “She was the one who was interested in stocks and T-bills and Canada Savings Bonds,” Rick remembers.

The family lived in a modest one-and-a-half storey home, rode used bicycles and enjoyed camping trips in second-hand tents.

King’s parents passed away within a few months of each other about five years ago, and he was the executor of their wills. When he went through their financial records he discovered his parents had more than $1 million in savings. “So I’m just trying to emulate what my parents did.”

Building a million-dollar nest egg is a dream for many Canadians, though most probably put it in the same category as winning the lottery or playing in the NHL. Many believe that the only way to amass a portfolio that size is to have an enormous income, receive an inheritance, or sell your start-up to Google. And indeed, for some Canadians, it won’t be possible, because of low income, poor health, or personal or family issues. So we’re not naively suggesting that anyone can do it. But if you earn an above-average salary and you’re truly committed, reaching retirement age with a million-dollar portfolio probably isn’t out of reach. Here are seven steps to get you to seven figures.

1. Start early

It’s a cliché to say it’s never too late to start saving, but the truth is it’s hard to build real wealth in the last decade before your retirement date. Most middle-class millionaires developed good habits when they were in their twenties and thirties, even if they didn’t have large investment portfolios until much later.

Blake Klasios is well on his way and he’s only 18. After graduating from high school in 2013, Klasios took a year off to work a series of jobs at a golf course, a food packaging company and a law office, earning between $10.25 and $13.50 an hour. Klasios has long been interested in finance and he’s just started his first year in McMaster University’s bachelor of commerce program, which he hopes to complete without taking on significant debt. This spring he reached first financial milestone by saving $10,000. “The big goal for me was that five-digit number,” he says. “At that point I really pushed myself to think about what to do with it, in terms of investments and saving for university and the future.” It will be decades before Klasios adds those two additional zeroes to his portfolio’s value, but for now his greatest assets are time and good habits.

The surprising truth is that if you start at age 25 by saving just $276 a month (or 10% of your net income on a $40,000 salary), increase your contribution by 3% annually and earn a 6% return, you would hit $1 million by age 65 and you’d never need to kick in more than $750 a month. On the other hand, if you wait until age 45, your monthly contributions would need to start at more than $1,300.

2. Make saving a priority

Still think you can become a millionaire just by forgoing that daily $5 latte? Forget it: building a seven-figure portfolio takes a lot more than that. In his new book Wealthing Like Rabbits, Robert Brown suggests you start by maxing out your RRSP every year. Most Canadians don’t come anywhere close to doing that, but no one said this would be easy. The RRSP contribution limit is 18% of your earned income, so if you’re pulling in $50,000 a year that works out to $750 a month—or roughly 150 lattes.

“I believe it’s realistic for most people,” Brown says. “But you really have to want this. It needs to be a goal you set for your life, and you make a commitment to it.” Brown reminds people that after the tax refund from your RRSP contribution, you’ll still have 85% or 86% of your income left over, and “someone else out there is getting by on that much, so you can too if you take that mindset.”

If you’re a salaried employee, set up automatic payroll deductions and join any savings program your workplace offers, especially if the employer matches at least part of your contribution. Then make a point of increasing your contribution every time you get a salary increase. That’s what Keisa Kuniecki is doing. The 36-year-old mother of two in Cambridge, Ont., takes advantage of her employer’s pension plan, group RRSP and a stock-purchase plan that allows her to have 5% of her salary matched by her employer. That commitment allows her to automatically save for retirement while also carrying a mortgage on the home she shares with her husband Rob and their two children, aged five and 18 months.

3. Don’t buy too much home

Buying a house can be a huge step toward financial independence: your retirement will feel more secure if you’re living in a paid-off home. But you won’t be able to build a seven-figure retirement portfolio if you’re house-poor. Indeed, buying a home that swallows most of your take-home pay is perhaps the biggest obstacle to savings.

“If you make a mistake and overspend on your credit card, you can probably take care of that in a short period of time by being disciplined,” Brown says. “But if you buy a house that’s well above your means, you’re on the hook for that mortgage and those bills indefinitely unless you decide to sell it.” If your family has become accustomed to a comfortable home in a friendly neighbourhood, being forced to downsize will be painful, even depressing.

The Kings are still in the same four-bedroom house in North Toronto they bought in 1997. “It’s a nice home, on a decent lot with a private driveway,” Rick says, but the countertops are Arborite and there’s no glint of stainless steel from the appliances. “A couple of years ago we were looking at million-dollar homes, but I just didn’t want to pull money out of our investments and put it into more house than we actually need.” King knew it wasn’t just a matter of the difference in listing price. “It’s all the other costs: the land transfer taxes, the real estate fees, the moving costs, the utilities, the increase in property taxes, and all the ongoing costs. My parents managed to have a modest home with six of us, so I figure the three of us should be able to live in a four-bedroom house.”

Rob and Keisa Kuniecki also decided they wouldn’t let a huge home purchase imperil their financial goals. Although they both work in Brampton they bought a home in less-expensive Cambridge, about 70 kilometres to the west, and commute about an hour each way. “We wanted to make sure our home would be manageable on one income,” Keisa says. The couple is making accelerated weekly payments and they’ve kept those payments the same even when their variable mortgage rate has gone down. “You’d be surprised at how much more quickly you build equity that way.”

Brown has a little trick you can use to pay down your mortgage even more quickly. Instead of choosing a five-year term, he suggests renewing every three or four years, and knocking a year off the total amortization period each time. Let’s say you take out a traditional 25-year amortization with a three-year term. When you renew you would have 22 years left, but Brown suggests you renew with another three-year term and a 21-year amortization. When you renew again three years later, you use a 17-year amortization instead of 18, and so on. The increase in your monthly payment would not be dramatically higher: for example, a $300,000 mortgage at 3.5% with a 22-year amortization would cost $1,631 a month. Over 21 years it would be just $51 a month more. “That gets you moving your finances in the right direction, as opposed to people who keep extending their mortgage at every renewal.”

4. Don’t buy too much car

While a home—even one that strains your cash flow—can appreciate in value and help you build wealth, the same can’t be said for what’s parked in the driveway. Most people need a vehicle, maybe two, and if you can afford a luxury ride without compromising your long-term goals, then go for it. But if the payment on your leased BMW is higher than your RRSP contribution, you’ve got a problem.

That’s another lesson Rick King learned from his dad. When King got his first high-paying job, he decided he deserved a high-end car. “I was looking at Corvettes and RX7s and my father took me aside and said, ‘Rick, rather than going out and buying a top-of-the-line sports car, why not buy a car that’s a little bit better than the one you have now. Then every time you buy a new one you can look forward to adding a few more options.’”

Rob Kuniecki picked up a new Nissan Versa two years ago and he says it’s now worth less than half what be paid, even with just 40,000 kilometres on the odometer. He’ll never buy another new vehicle. “The depreciation will kill you,” he says. “Just get a good reliable automobile and a good mechanic. That also keeps your insurance costs low.” Rob now drives a 10-year-old GMC Envoy that he paid just $6,000 for. “It probably has about half of his life left, and I paid one-tenth of the original value.”

Even Blake Klasios has figured out that buying a car would have derailed his savings plan. “When I worked at the golf course I was looking at buying a car, but I figured that with insurance and gas and everything else it would have cost me about $3,500 or $4,000 for the year. So I put it off, and I eventually just lost interest in buying a vehicle. That was a smart decision.”

5. Be frugal, not cheap

People who make saving a priority aren’t planning to die with a million bucks in the bank. Rather, like Rick King, they want to enjoy the freedom to see a job loss at age 57 as an opportunity instead of a catastrophe.

Saving is a means, not an end. It’s a decision to spend your money thoughtfully on things that give you lasting enjoyment. People who are unable to save are often at a loss to explain where all their money goes, a sure sign that much of it is being wasted on purchases that don’t give them any real pleasure. Blake Klasios has discovered that one of the best ways to spend your money thoughtfully is to keep a record of all your purchases. He uses Mint.com, a free money management system you can use with your smartphone. “Even if you don’t make a budget, just by watching the trends, whether it’s shopping for clothes or buying food, you start to see your spending way too much on this or that. You start asking yourself whether this is really necessary.”

Brown says a frugal lifestyle is often portrayed as a sacrifice—or worse, as being miserly. “It’s important that people recognize frugality doesn’t mean being cheap.” A frugal couple might dine at home with a $15 bottle of wine to celebrate a birthday instead of dropping $150 at a restaurant. A cheap person doesn’t buy his wife a present.

Everybody needs to have a few indulgences, Brown says, but you should look for ones that are affordable. For example, rather than going a restaurant, he and his wife often have a home-cooked meal and then go for dessert and coffee at Starbucks. That way their evening out costs $12 instead of $80 or more.

Rob and Keisa Kuniecki have their own routine. “We don’t go out for dinner very much,” Rob says. “But we watch a lot of cooking shows and try out different recipes. We still eat well: we have a steak dinner once a week, but I do it myself on the barbecue.”

Brown’s book suggests a low-cost indulgence for stressed-out parents: sex. “Send your little ones off to Grandma and Grandpa’s place for the night. Cook a nice meal together, polish off a bottle of wine, get romantic, and sleep in the next morning,” he writes. “You’re welcome.”

6. Have an investment plan

The next step on your path to a million dollars is a commitment to disciplined investing. While it’s crucial to spend less than you earn and save the difference, you probably won’t be able to grow a seven-figure portfolio by putting that surplus income into a bank account paying 1%. You need a plan for earning a decent return on your hard-earned savings.

For some investors, like Rick King, that might mean building a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. Rob Kuniecki enjoys looking for value stocks, but he’s more comfortable investing in real estate. “I’d like to pick up a rental property, or perhaps get into lending out money for second mortgages,” he says. The right strategy for you is the one you’ll stick to with confidence over the long term.

Always be aware of the corrosive effect of high investment fees. A 2013 Morningstar report declared Canada’s mutual fund fees and expenses the highest of the 24 countries they examined, with the average fund cost coming in at over 2%. If you’re trying to earn a long-term return of 5% or 6% on your retirement savings, that’s a huge hurdle to overcome.

If you’re paying an adviser, you also need to ask yourself whether you’re getting value for his or her fee. If you’re getting unbiased financial planning and a disciplined investment strategy for a reasonable fee, good for you. But if your adviser does little more than pick high-fee mutual funds and encourage you to borrow to invest, chances are you’re not going to be the millionaire in that relationship.

There are plenty of low-cost solutions for investors who are prepared to manage their own accounts: a single balanced mutual fund with a fee of 1% or so is a simple RRSP solution that’s likely to deliver better results than many Canadians are getting from their advisers. Once your portfolio is well into six figures you should also consider a fee-based adviser who can provide unbiased investment advice and help you set realistic goals.

7. Let your plan evolve over time

Your path to a million bucks doesn’t have to be perfect, and it doesn’t have to be plotted out 30 years in advance. You don’t need to save a fixed percentage of your income like clockwork throughout your career—nobody does that. “It’s easy to talk about saving 18% of your income every year without ever missing an RRSP contribution, or putting a 20% down payment on a house before the age of 30,” says Brown. “The reality is, life is never that easy. The trick is to try stick to the fundamentals, even imperfectly, and adapt them to your situation.”

Your plan should evolve over the years as your life situation changes, your income grows and your priorities shift. But if you follow the steps we’ve outlined here, chances are things will work out well. Even if you never quite reach that seven-figure mark—and it’s an arbitrary number, after all—your retirement will still feel like a million bucks when you get there.

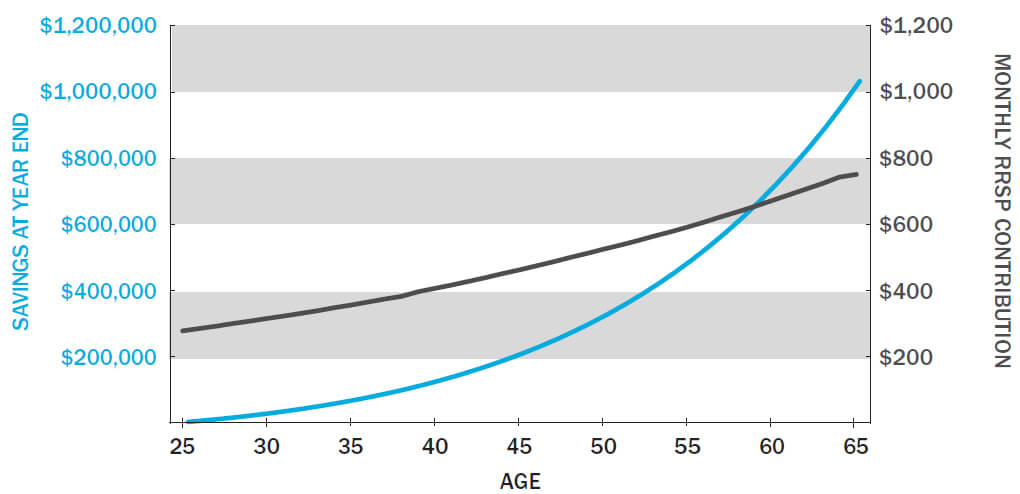

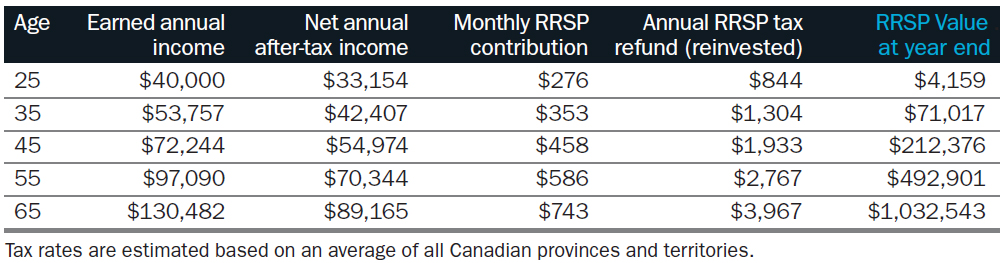

The model millionaire

If you start saving early, you won’t need to make a huge income or max out your RRSP to build a million-dollar nest egg. Here we assume you earn $40,000 at age 25 and your salary increases by 3% annually. You save 10% of your net income in your RRSP and reinvest the tax refund each year. If you can earn an average return of 6% annually, your portfolio would grow to over $1 million by age 65.

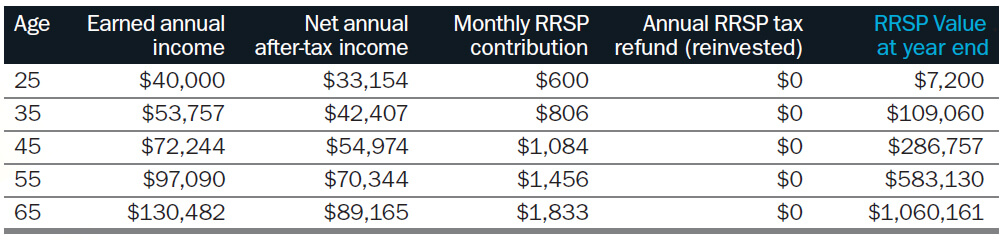

The super-safe saver

If you’re a conservative type who sticks to GIC rate and other safe investments, you’ll need to save more to make up for the lower expected returns. Here we assume you’re maxing out your RRSP every year, so your contribution is 18% of your earned income. (Since you’re using up all your contribution room, you can’t reinvest the tax refund.) We assume a low-risk annualized return of 3.5%.

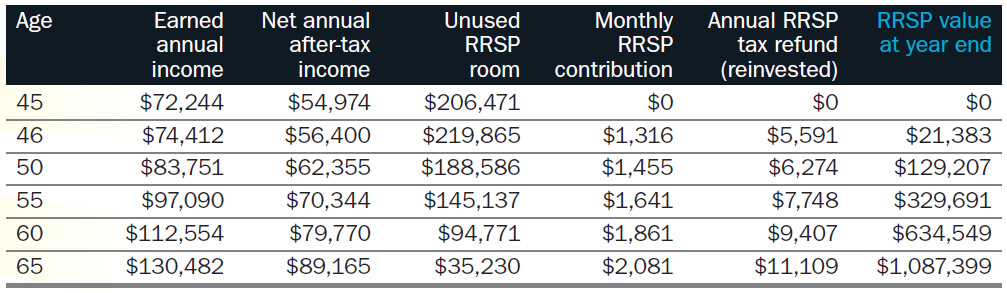

The late-blooming millionaire

Many people find it hard to build real savings until after they’ve tackled their mortgage. But even if you’ve saved nothing at age 45 you can make up for lost time by saving as much as you used to spend on your mortgage payments. By saving 28% of your income (subject to RRSP contribution limits) you can still hit a million by age 65, though you’ll need an annualized return of 7%.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email