Making sense of the markets this week: April 2, 2023

No love for banks in the 2023 federal budget, Dollarama and Lulu stretch profits, banks stabilize (for now), and the money/happiness link is pretty nuanced.

Advertisement

No love for banks in the 2023 federal budget, Dollarama and Lulu stretch profits, banks stabilize (for now), and the money/happiness link is pretty nuanced.

Kyle Prevost, editor of Million Dollar Journey and founder of the Canadian Financial Summit, shares financial headlines and offers context for Canadian investors.

There are several big-picture looks at the important aspects of the Canadian federal budget that was unveiled on Tuesday. For this week’s “Making sense of the markets this week” column, we’re focussing on two lesser-reported items buried in the details: A new measure aimed at Canadian banks, and another at corporate shareholders. (Read MoneySense’s full coverage of the 2023 federal budget.)

If you’re a Canadian bank shareholder you may already be smarting from the hit you took in the last budget when the Canada Recovery Dividend was announced, and an extra 1.5% corporate tax was placed on banking and life insurance companies.

On Tuesday, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland announced that the Income Tax Act would be amended, and that dividends received on Canadian shares held by Canadian banks and insurers would be treated as business income. This change is forecast to take $3.15 billion out of shareholders’ pockets over the five years beginning in 2024.

Given that the banking sector, as a whole, provides a relatively inelastic good, and the fact that Canada’s banks and insurers operate in an oligopolistic market structure, it’s fair to assume that the vast majority of these tax hits will be passed right along to consumers.

In other words, banks and insurers know Canadians need their banking services and they have (almost) nowhere else to go. These institutions, rather than take the hit to the bottom lines, will just raise the prices of financial products and services.

All this comes at a time when banks are likely to find it more expensive to capitalize themselves due to last week’s worldwide revelation of the risk involved in convertible bonds.

You can read more about Canadian bank stocks on MillionDollarJourney.ca.

The other interesting budget detail: The 2% share buyback tax. For those unfamiliar with the term “buyback,” know that it is when a company uses its profits to “buy back” its shares. This activity pushes share prices higher, allowing shareholders to potentially sell their shares for profit. The whole point is to pass along profits to shareholders in a tax-efficient manner. Investing titan Warren Buffett recently defended the practice.

The Liberal Government suggests this new tax will incentivize companies to reinvest profits instead of rewarding shareholders. Predictably, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce are not fans of the changes in taxation law.

If the Canadian federal government wants retail investors and corporations to put more money in Canada, perhaps it should incentivize investing—and not make it less attractive.

Three Canadian companies from very different sectors of the economy reported earnings this week as BlackBerry, Dollarama and Lululemon opened their books. (All values are in Canadians currency, unless otherwise noted.)

Despite posting a meagre profit in 2021’s fourth quarter, BlackBerry reported a US$495 million loss. CEO John Chen blamed the negative earnings results on delays from several large government cybersecurity contracts. Shareholders are likely to grow increasingly restless as the company continues to try to claw its way back to profitability based on cybersecurity specialization. BlackBerry has roughly three years left of solvency, given its current cash burn rate.

Lululemon shares (which have traded exclusively on the NASDAQ stock exchange since 2013) jumped more than 14% on Wednesday. That came after the news of its earnings and a very strong 2022 holiday shopping season. Lulu’s overstocked inventory issue from the third quarter last year looks to have corrected itself. Overall, the company appears to be on a solid footing as same-store sales were up 27%, year over year.

Meanwhile, Dollarama should be excited to report its profits grew by 27% year-over-year in 2022, andcredited inflation-conscious shoppers for its increased foot traffic. And now, Dollarama shareholders have a 28% higher dividend to look forward to. With 60 to 70 new stores opening next year, Canada’s premier dollar store should continue along its growth trajectory.

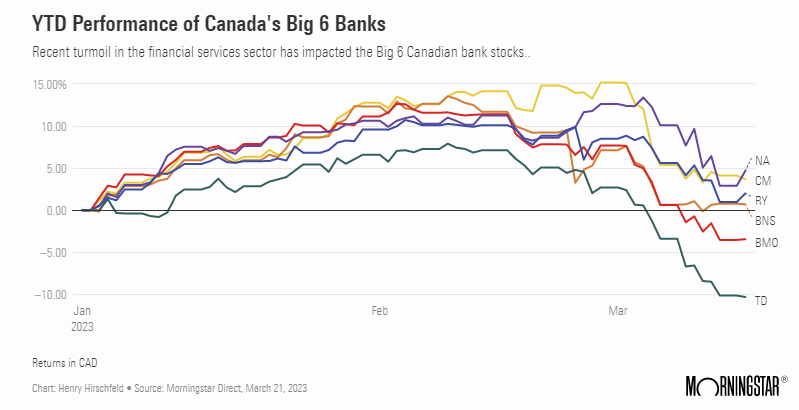

First we had the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and cryptobanks debacle from a couple of weeks ago (since stabilized after First Citizens Bank took over operations); then last week, it was Europe’s turn to worry about its banks going under.

Confidence in the structural integrity of the broader financial system appeared to be mostly restored this week.

That said, this scary couple of weeks might end up working very well for the world’s central bankers, thanks to a few unintended consequences. In my explainer on convertible “coco” bonds, I posited that the financial instruments had not been valued correctly from a risk/reward perspective. It appears that many investors from around the world agree.

S&P Global Ratings concurred:

“An increased focus on downside risk could increase banks’ cost of capital and make new AT1 issuance more difficult and more expensive. Jittery investors will take some time to revise their perceptions of risk for individual banks and instrument structures.”

Basically, for retail banks and lenders, this means is it’s going to cost more money to get Tier 1 capital needed in order to make sure 2008 doesn’t happen again. So, they’ll have to pay investors a higher yield to encourage them to buy convertible bonds. And that means they’re not likely to issue as many of these bonds as they have in the past. That all adds up to less lending over the long run.

It’s also true that, as regulators get more involved in the banking sector and emphasize safety over profits, bank managers will be compelled to hang on to more deposits as they come in.

Less lending means less spending on everything, from houses to skyscrapers. This credit crunch is likely already being felt by both large corporations and retail consumers. It could be especially rough for folks in the American commercial real estate industry, as nearly 70% of U.S. real estate loans are generated by the same regional banks that are now under the regulatory microscope thanks to the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

Finally, while it’s hard to quantify, it remains no less true that an economy’s “animal spirits”—how people feel about financial stuff—are major contributors to the direction it heads into for the short- and medium-terms.

If all North Americans are hearing and reading about is record-low unemployment numbers and inflation headlines, they’re more likely to ask for raises or accept higher prices at their usual store. If that information cycle is suddenly replaced with panic-induced negative sentiment, we’re more likely to spend less and not feel as confident negotiating our salaries and benefits.

All these outcomes are great news, if you’re a central banker looking to slow the economy without breaking anything else. It’s also pretty good news if you’re a stock market investor feeling increasingly stressed by steadily rising interest rates.

“Money does not buy you happiness, but a lack of money certainly buys you misery.”

—Daniel Kahneman

Back in 2010, Nobel-prize winning researchers Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton released a landmark study to show that a household income of USD$75,000 (USD$103,000, adjusted for inflation, which is about $139,000 in Canadian dollars) best predicted happiness.

Their research showed that families earning below $75,000 could benefit from more money. But those with more didn’t show a correlation with increased happiness. The findings meshed well with the belief that “money can’t buy happiness” and that people could think, “Rich people are miserable, so I’m OK not being rich.”

Then in 2021, Matthew Killingsworth, senior fellow at Penn’s Wharton School, came along and ruined that feel-good story about more money meaning more problems. He found that happiness increased quite strongly after that $75,000 level, and “There was no evidence for an experienced well-being plateau above $75,000.”

In order to settle their dispute, Kahneman threw down the gauntlet and challenged Killingsworth to a cage fight—for researchers, that means to collaborate on a new paper.

Killingsworth’s name comes first in the citations, so maybe this means his hand was raised at the end of the fight.

What the authors discovered, when they put their respective theories to the test, was an interesting bit of nuance. It turns out that earning more than $75,000 will probably make you happier, but only if you were in the happiest 80% to begin with.

Kahneman and Killingsworth together concluded:

“There is a plateau, but only among the unhappiest 20% of people, and only then when they start earning over $100,000.”

If you had a baseline level of happiness, then the diminishing returns of a high income only start to kick in after $500,000.

That intuitively feels more right.

It would be great to have a follow-up research paper looking at the overall net worth or savings of people as it relates to happiness. I’d pay to read that, especially if they packaged it with a rematch for the “Econ Academic-weight Championship Belt.”

Kyle Prevost is a financial educator, author and speaker. When he’s not on a basketball court or in a boxing ring trying to recapture his youth, you can find him helping Canadians with their finances over at MillionDollarJourney.com and the Canadian Financial Summit.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email