Family profile: Pulling up their roots

Pierre and Jackie have worked hard and lived modestly in rural Quebec. Now that Jackie has lost her job, they wonder if it’s time to sell their 117-acre farm so they can enjoy the fruits of an early retirement.

Advertisement

Pierre and Jackie have worked hard and lived modestly in rural Quebec. Now that Jackie has lost her job, they wonder if it’s time to sell their 117-acre farm so they can enjoy the fruits of an early retirement.

Until a year ago Pierre and Jackie Moreau were living the Canadian dream. Jackie, 48, had a satisfying job as an estimator for a construction company in North Hatley, Que., just a five-minute drive from home. Pierre, 54, ran the family farm they’ve owned since they were married 23 years ago. Then last year Jackie, the main breadwinner, lost her job. “I had worked at the same company for 22 years,” says the mother of three teenage daughters—Loraine, 19; Rina, 16; and Marie, 15. “I was making $60,000 a year—more than twice the income we get from the farm—so we lived a very comfortable middle-class life. But now, with my income gone, we have to rethink everything. Good-paying jobs are almost impossible to find here and we can’t survive on the farm income alone. We need to do things differently.”

While the Moreaus (we’ve changed their names to protect privacy) first considered Jackie’s job loss a crisis, they are beginning to see it as an opportunity. In fact, coupled with the unpredictability of farming, it’s causing them to rethink their entire future. For instance, before Jackie’s job loss they never thought much about early retirement. But now, doing more with what they have—and using their assets more wisely—is a constant topic of conversation. “Losing my job and spending some time at home has made me see there are other things I’d like to explore besides working full-time at an office job until I’m 65,” says Jackie. “I’d like to try working only part-time, or, if we have enough savings and plan it right, maybe I won’t have to work at all any more.”

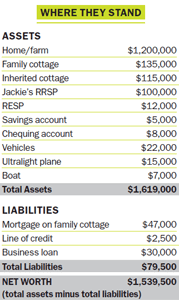

What allows the Moreaus to consider these options isn’t the farm income—it’s only $25,000 a year before tax, less than half what they need to maintain their lifestyle. But like most long-time farmers, Pierre and Jackie have an ace in the hole: the equity in their 117-acre corn, soybean, beef and grain farm. It’s been appraised at $1.2 million. More and more, they’ve been thinking about selling the farm, investing the money and downsizing to their cottage. “I’ve enjoyed farm life, but farming isn’t an old man’s game,” says Pierre. “Once our daughters are all out of the house in three years, I’d like to see the world. But we’re not sophisticated investors. We need a plan to unlock the wealth we’ve built up in our real estate so we can kick our feet back and start enjoying life a little.”

The couple’s assets include their farm, the family cottage worth $135,000, and a second cottage they inherited from Jackie’s father last spring worth $115,000. “Having more free time has its benefits,” says Pierre, who loves the outdoors. “We can golf, fly, travel and spend more time at the cottage. But if I continue farming, we’ll always be trying to sandwich the fun stuff between the farm stuff, and that’s stressful.”

What worries Pierre most is that he may never enjoy the fruits of his labour. “We honestly love farm life but the business of farming, that’s why you have to retire. It drains you pretty quickly and you can’t do as much as you get older. I really want to enjoy life while we’re still young. I’ll always remember Jackie’s 69-year-old father telling me how upset he was that he had worked so hard farming his land and then couldn’t access the money because he was afraid to sell. I don’t want that to happen to us.”

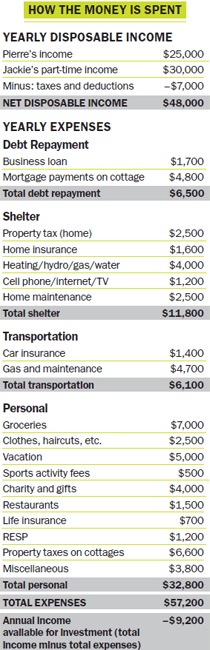

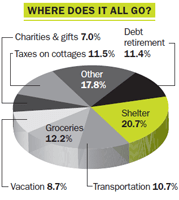

The way the Moreaus see it, they have a few options. In the first scenario, if Jackie works part time and earns $30,000 a year, half what she earned before—that’s what we’ve assumed in their household budget, at left—the Moreaus will have a $9,200 gap between their net income and what they will need to cover expenses. Jackie thinks they can fill that gap by withdrawing money from her $100,000 RRSP.

But what if Jackie can’t find a part-time job—a likely scenario? Then she would drop out of the workforce and retire. That’s enticing because it means Jackie can spend more time with the couple’s two younger daughters before they leave for university. “I really love being home but that means we’d have to fill a roughly $40,000 a year income gap to cover our expenses,” says Jackie. “I don’t know if we could afford that for long, even if we dipped into our RRSPs.”

Jackie and Pierre realize that withdrawing $40,000 or so from their RRSP would exhaust those savings in less than three years. But taking money out of the RRSP to cover the annual difference seems like the easiest option. “The $13,000 we have in our savings and chequing accounts is earmarked for renovations on the cottage we inherited,” says Pierre. “It’s worth about $115,000 and we can rent it for $8,000 a year when the renovations are done. But I’m not sure we really want to be landlords at this stage of our lives.” In fact, the couple acknowledges they may be better off just selling it.

Jackie, who has always managed the family’s money, has worked hard to pay down the mortgage on their farm, even when Pierre insisted on buying his toys. “Five years ago he bought a boat, and then shortly afterwards he bought a plane so he and our daughter could take flying lessons,” says Jackie. “I made sure we could pay for those in cash.”

These days, Jackie is taking a much more hands-on approach with their investments. The $100,000 in her RRSP is invested in mutual funds, but she’s in the process of switching to exchange-traded funds to save on costs. The couple would also like to eliminate their $80,000 debt and make a final decision on what to do with the cottage they inherited. “That cottage may be our escape hatch,” says Pierre. “We could rent it out or sell it. It’s tough to know which is really best for our bottom line.”The couple married in 1989 and bought the farm shortly afterwards. Jackie got her job as an estimator and her full-time income over the years has allowed the family to live comfortably. But while she paid down the mortgage, shopped frugally for groceries, clothes and insurance and tried to put some money in savings, she and Pierre seldom took an interest in investing until the last few years. So while selling the farm will be a bonanza, their biggest question is how to invest the proceeds. “Once the kids are gone, we know we could live on $40,000 net a year,” says Pierre, who wonders whether the $1.2 million can generate that kind of income for the rest of their lives.

When they finally sell the farm, they’d like to make the family cottage their primary residence. But they won’t do that until they feel confident their nest egg from the farm will be invested wisely. “Somehow having $1.2 million in a bank somewhere doesn’t feel very secure to us,” says Pierre. “It’s strange, because we’re farmers for crying out loud, and farming is the riskiest thing you can do. But we can’t afford for the money to run out. So we really need the right income-producing strategy and we need to feel fully comfortable with it. When we do that, we can relax and start enjoying life.”

When they finally sell the farm, they’d like to make the family cottage their primary residence. But they won’t do that until they feel confident their nest egg from the farm will be invested wisely. “Somehow having $1.2 million in a bank somewhere doesn’t feel very secure to us,” says Pierre. “It’s strange, because we’re farmers for crying out loud, and farming is the riskiest thing you can do. But we can’t afford for the money to run out. So we really need the right income-producing strategy and we need to feel fully comfortable with it. When we do that, we can relax and start enjoying life.”

By living frugally and paying off their farm, Jackie and Pierre now have assets worth more than $1.5 million. At their relatively young ages of 48 and 54, they feel ready for a little financial freedom before the traditional retirement date of 65. And if their only problem was the numbers, the answer would be easy. “Sell the farm and the inherited cottage, pay off the debt and invest the rest,” says Heather Franklin, a fee-only adviser in Toronto. “It doesn’t have to be daunting. If the income from the sale of the properties is structured properly, the money from a well-balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds will last them a lifetime.”

Al Feth, a fee-only adviser in Waterloo, Ont., agrees but cautions that while selling the farm may make sense financially, “it may not be a good fit emotionally” with two teenage daughters still living at home.

Jason Heath, president of Objective Financial Partners in Toronto, thinks the Moreaus really need to focus on where they want to be in five or 10 years. “Right now, 88% of their investments are in real estate, so that in itself is risky,” he says. “What they need to do over the next few years is slowly sell some real estate and use the proceeds to build a portfolio that produces solid growth and income.” Here are some suggestions:

Sell the inherited cottage. The couple doesn’t need the second cottage, and it will add little or nothing to their bottom line. “There is no benefit to renting it,” says Feth. “Once you pay for property taxes and other expenses, there will be little left from the $8,000 in rental income.” Instead, Feth says the couple should sell the cottage, take the $110,000 proceeds and pay off the roughly $80,000 they have in mortgage, business and consumer debt. Besides making them debt-free, it will also mean their annual expenses will be reduced by about $9,600 ($6,500 less in debt repayment and $3,100 less in cottage property taxes). Then their budget will balance if Jackie gets a part time job making $30,000 a year. “If it’s a job she likes and it brings in this steady income, that may be all the couple has to do for the next three years until the two teenagers are off to college,” says Feth.

Consider RRSP withdrawals. But what happens if they sell the second cottage, pay off their debt, and Jackie can’t get part-time work? The couple will have to make up the $30,000 annual shortfall starting in 2014. They can do that by withdrawing money from Jackie’s RRSP. “If she has no other source of income, she can make withdrawals of $30,000 annually and pay very little tax,” says Heath. “This strategy will last them just over three years until the RRSP is depleted. That may be a good time to sell their farm.”

Sell and downsize. “As the Moreaus get closer to retirement, owning a farm is actually a lot riskier than owning a well-diversified investment portfolio of equities and bonds,” says Franklin. She advises the couple to sell the farm sooner rather than later and downsize to the family cottage. “Pierre will be slowing down by then,” she says. “They’ll need a steady income of $40,000 after taxes. A well-diversified portfolio built with the money they get from selling their farm will give them that.”

Build up an emergency fund. Once the farm is sold, the Moreaus should take $100,000 from the sale—just over two years’ worth of expenses—and put it into a savings account. (In 2013, they will have $50,000 in TFSA contribution room, so they can shelter half from taxes.) This will be an emergency fund they can draw on if the stock market has one or two bad years. “The rest of the portfolio should be made up of mainly high quality blue-chip stocks, exchange-traded funds and some bonds that provide a steady income,” says Feth. “They should seek the help of a fee-only adviser to put a conservative portfolio together for them—60% dividend-paying stocks and 40% bonds and real estate investment trusts—and, with Jackie’s help, the portfolio should be monitored at least once a year.”

To add an extra level of safety, Heath advises the couple to slowly build their portfolio over two years. “Dollar-cost averaging will be key for them,” says Heath. “They don’t want to take the chance of putting all of their money in at the top of a market cycle.”

Once their $1.1 million is invested, Feth says the couple can withdraw 4% (or $44,000) annually from their portfolio for a few years while they live comfortably at their cottage and travel. “A well-balanced portfolio should easily be able to give them a 4% average annual rate of return, so they won’t even have to touch their principal.” Then, once Jackie and Pierre both reach age 65, Jackie’s CPP ($5,000 annually) and their OAS payments ($12,800 annually combined) will mean they can lower their portfolio withdrawals to just 3% annually, or about $33,000, and still live very comfortably. Using this strategy will guarantee the couple income for life. “If they do all this, they should still have $1 million at age 90, plus their cottage,” says Heath. “This plan will see them through a very bright future.”

Julie Cazzin is an award-winning business journalist and personal finance writer based in Toronto.

Would you like MoneySense to consider your financial situation in a future family profile? Drop us a line at [email protected] If we use your story, your name will be changed to protect your privacy.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email