Single retirees: The power of one

Meet three sixty-something singles who breezed past those obstacles and made it work

Advertisement

Meet three sixty-something singles who breezed past those obstacles and made it work

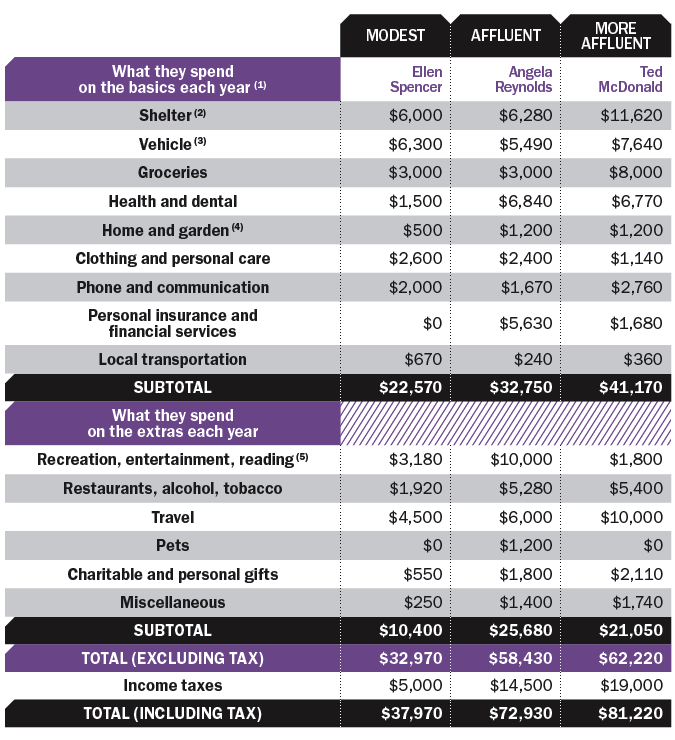

(1) Annie Kvick of Money Coaches Canada helped estimate these budgets. (2) Includes property taxes, utilities, maintenance, home insurance, rent and mortgage payments. (3) We’ve added $2,000 a year for depreciation. (4) Includes cleaning supplies, furnishings, appliances, garden supplies and services. (5) Includes computer equipment and supplies, recreation vehicles, games of chance, educational costs.

(1) Annie Kvick of Money Coaches Canada helped estimate these budgets. (2) Includes property taxes, utilities, maintenance, home insurance, rent and mortgage payments. (3) We’ve added $2,000 a year for depreciation. (4) Includes cleaning supplies, furnishings, appliances, garden supplies and services. (5) Includes computer equipment and supplies, recreation vehicles, games of chance, educational costs.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email