The savings struggle: TFSA vs. RRSP

Here’s how to choose the right strategy for your retirement dollars

Advertisement

Here’s how to choose the right strategy for your retirement dollars

The RRSP deadline looms and the new year brings an additional $5,500 of contribution room for Tax-Free Savings Accounts. You’d probably love to maximize contributions to both RRSPs and TFSAs, but most people can’t afford to do that—especially if they’re carrying a mortgage and trying to sock a little away for their children’s education. So what’s the best way to save for retirement if you have limited funds?

With so many options fighting for your retirement dollar, the choice is not easy. Fortunately, we can help. In what follows, we’ll show you how to find the best strategy for your situation. As it turns out, the RRSP is ideal if you’re in a high tax bracket now and expect to end up with a solid middle-class retirement. But TFSAs are more flexible and work better if you retire with either a very high or very low income. Let’s delve into the details.

In the tug-of-war between RRSPs and TFSAs, the former is the reigning champion, since it’s where Canadians have most of their personal nest eggs. This year you have until March 3 to contribute for the 2013 tax year. But you should also consider the main contender for the savings crown, the TFSA, introduced in 2009. You can contribute up to $5,500 for 2014, or more if you have unused room from previous years.

Both RRSPs and TFSAs shelter you from tax as long as the investments are held within the account. With an RRSP, you can deduct the contribution from your income, which earns you a tax refund, but the money becomes fully taxable when you take it out. The TFSA is the reverse: you don’t get a tax break on contributions, but you don’t pay tax on withdrawals either. So if you’re deciding between the two options, the question boils down to whether you should pay the taxman now or later.

The answer depends on your tax rate. If you’re in a higher tax bracket when you put the money in than when you take it out, then it’s better to use an RRSP. It’s easy to understand why: your original RRSP contribution gives you a juicy tax rebate now, and the taxman takes a smaller bite on withdrawal. However, if you take the money out when you’re in a higher tax bracket than you’re in now, it’s better to go with a TFSA. If your tax rates are the same when the money goes in and out, then the choices are equivalent.

While that idea is simple, putting it into practice is far more difficult. After all, it’s impossible to forecast what tax bracket you’re going to be in decades from now. But while you can’t make precise predictions, most people live on far less income in retirement than they earned in their peak working years. So RRSPs make sense in many situations. In particular, they provide outstanding results if you’re a high-income earner saving for a typical middle-class retirement.

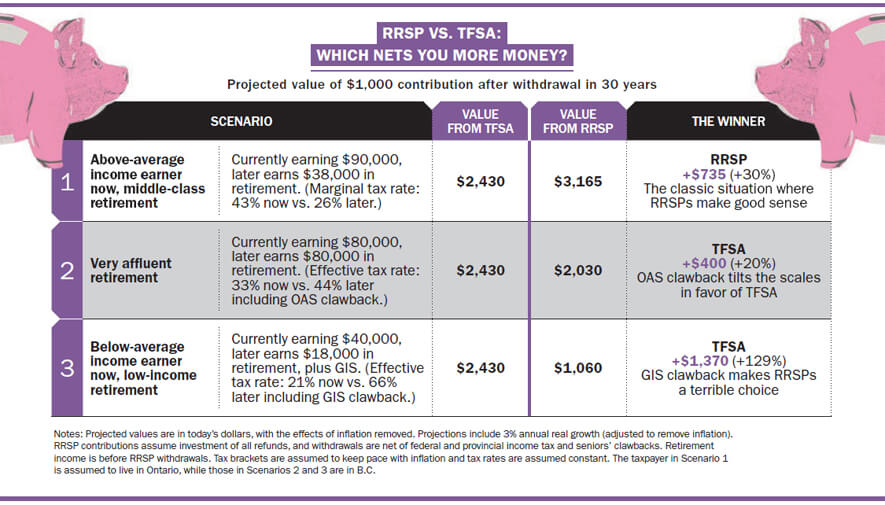

Here’s an example. (See Scenario 1 in “RRSP vs. TFSA: Which nets you more money?” below.) Say your current income is a healthy $90,000, and you believe you’re on track to have an income of $38,000 in today’s dollars when you retire in 30 years. In Ontario (where tax rates are close to the Canadian average), your salary would put you in a 43% tax bracket now, but you would pay only 26% in tax when you take the money out of an RRSP later, assuming rates stay constant and tax brackets keep pace with inflation. Thus, if you contributed $1,000 plus the tax rebate to your RRSP and you earn moderate returns, you could expect that money to be worth roughly $3,165 (in today’s dollars) after tax when you eventually draw it in 30 years. Putting the same amount into a TFSA would net you only $2,430. So the RRSP wins this bout by a wide margin.

But this example is a bit lopsided, because the difference in tax rates is so large. If the gap were smaller, the RRSP would still put you ahead, but not by as much.

There are many other situations where you’ll fare better with a TFSA, because it’s more flexible. For starters, dipping into a TFSA never has a tax impact, whereas you’re liable to pay an annoyingly large amount of tax if you need to draw on your RRSP for an emergency while still working. (You can take out specified amounts from your RRSP without tax consequences for a first-time home purchase or for education, but you have to repay those amounts according to rigid timetables or suffer serious tax consequences.) Furthermore, dipping into an RRSP results in a permanent loss of the contribution room, whereas with TFSA withdrawals you can put the money back after waiting until the next calendar year.

Even more important, you’re eventually forced to convert your RRSP to a RRIF or annuity by the year you turn 71 and then make mandated minimum withdrawals. By contrast, TFSAs come with remarkably few strings attached when it comes to withdrawals. So if you’re looking for flexibility—and especially if you might need the money while still working—the TFSA is the clear winner.

There’s another factor to consider when weighing the merits of RRSPs and TFSAs. When you start drawing down your savings in retirement, RRSP and RRIF withdrawals count as income, which may lead to a reduction of seniors’ benefits such as Old Age Security or the Guaranteed Income Supplement. “When you pull money out of an RRSP there are hidden taxes in terms of clawbacks,” says Camillo Lento, professor of accounting at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ont. Oddly, these benefit clawbacks don’t typically affect middle-income seniors much, but they have a far greater impact if you have either a high or low income.

Consider the impact on someone destined to achieve an affluent retirement, shown in Scenario 2 in our table. Say you’re a B.C. taxpayer now earning $80,000 a year and go on to enjoy exceptional financial success, eventually retiring on the same $80,000 (in today’s dollars). In that case, expect your RRSP withdrawals to be hit by the dreaded clawback of OAS benefits. The government claws back 15 cents of OAS for each $1 of income when total taxable income is between $70,954 and $114,640 for the 2013 tax year (although the net impact is less because the clawback in turn reduces taxable income). Overall you’d end up $400 (or 20%) ahead by putting the $1,000 into a TFSA instead of an RRSP. So for well-off retirees, the TFSA wins by a solid margin.

The impact of RRSP withdrawals on clawbacks is even more severe at the other end of the income spectrum, where seniors may qualify for the Guaranteed Income Supplement: GIS. (To be eligible for GIS, seniors must earn less than about $23,300 for singles or $35,300 for couples in 2013, not counting certain types of income.) That’s because each dollar of RRSP withdrawal will cost you about 50 cents in GIS clawbacks. “That’s like a 50% marginal tax rate,” says Malcolm Hamilton, retired actuary and fellow with the C.D. Howe Institute.

As we show in Scenario 3, say you currently earn $40,000 a year in B.C., then later earn $18,000 as a retired senior. Your $1,000 contribution (plus tax refund) to an RRSP will have grown to more than $3,000 over 30 years, but you would effectively lose two-thirds of it to income taxes and GIS clawbacks when you take the money out. In that case, contributing instead to a TFSA would put you $1,370 (or 129%) ahead.

As we’ve said, it’s impossible to know what your income will be like in retirement if you’re still many years from that milestone. So if you’re not clear about which situation will apply to you, how do you decide?

An important factor to consider is whether your employer matches your contributions to a workplace retirement savings plan. So if your company tops up your voluntary contributions to a group RRSP, you should make it your priority to contribute enough to get the match—free money from employers trumps other options.

Absent that kind of plan, the flexibility of TFSAs makes it the best default option. “The TFSA is probably the safer choice if you don’t have a clear sense the RRSP is the right thing,” advises Hamilton. He thinks it’s likely tax rates and income-related clawbacks will rise over time, which tilts the scales further in favour of TFSAs. But unless you end up as a GIS recipient (in which case RRSPs would be a big mistake), you won’t go wrong with either option, he says. “For most people, these are two good choices.”

Lento also likes the TFSA’s all-around strengths. “If you’re in a very high tax bracket and know you’re going to bring that down in retirement, that would be the only time I would make an RRSP the priority,” he says. If you opt for the RRSP, make sure you don’t spend the tax refund. “If you don’t invest the rebate, the TFSA becomes far superior,” Lento says.

If you’re trying to decide whether the RRSP rebate is big enough to be worth it, one threshold to consider is whether your taxable income is above $43,561 for 2013, which is the dividing line between the first and second federal income tax bracket. (“Taxable income” is your income after certain deductions, including those for RRSPs and child care expenses, and is shown on line 260 of your tax return.)

If your income is above that level, your marginal tax rate jumps seven percentage points, and therefore your RRSP contributions will garner a bigger rebate and make it fairly likely you’ll end up ahead. Below that line, the benefit of going with RRSPs is more questionable. Also, at lower current income levels, you’re more likely to be a GIS candidate later on, especially if you’re single.

Until now we’ve considered only the relative benefits of RRSPs and TFSAs, but there are other options for putting that extra cash to work. If you have a big mortgage, you may be tempted to forego your retirement savings and instead pay down that debt. That idea is consistent with the “mortgage first” strategy advocated by Malcolm Hamilton, in which you first focus your efforts on paying off your home as quickly as possible, then build your retirement savings later in a concentrated period.

The tax advantages you get from this strategy may not be as obvious as with an RRSP, but they’re still important. Paying down mortgage principal reduces future interest payments that you would need to pay with after-tax income. Owning a home that appreciates in value is also a kind of tax shelter, since you won’t pay capital gains tax when you eventually sell. In addition, the investment return is attractive considering that it’s guaranteed. “You’ll get a better risk-adjusted return paying down the mortgage than you’ll get anywhere,” Hamilton points out. Mortgage rates are always higher than the GIC rates and government bonds of the same term because working that spread is part of how banks make money.

If you have children, the best savings program with a four-letter acronym might be the RESP, for Registered Education Savings Plan. Only you can determine the right balance between contributing to your kids’ education and saving for your own retirement, but there’s an argument to be made for prioritizing the RESP, especially if you’re a young parent.

You may have the option of delaying your retirement and working a little longer—you may even prefer to do so. But you have a short window of opportunity to save for your child’s education: to take full advantage of the generous government grants available, you’ll need to open an RESP no later than the year your child turns 10, and you’ll have to make all the contributions by the year she turns 17.

The government will match 20% of your contributions for each child to an annual maximum grant of $500 and a lifetime limit of $7,200. (You get a bit more in Alberta or Quebec, or if your family has below-average income.) To maximize the grants, you’ll need to contribute a total of $36,000. You’re allowed to contribute up to $50,000 per child, but in my view you should stop after you’ve maxed out the grants. RESPs are complex, and have many restrictions when it’s time to take the money out, so it makes more sense to place additional education savings in the more flexible TFSA.

You need to understand the tax rules and rely on some assumptions if you want to get the most out of your retirement dollar. But once you know the strengths and weaknesses of each savings option, you’ll have the confidence to pick the right champion for your retirement plan.

David Aston, CFA, CMA, MA,writes about personal finance. You can send him questions, comments and suggested article topics at [email protected]

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email