When to retire to maximize your money

See how much of a difference working past age 65 can make

Advertisement

See how much of a difference working past age 65 can make

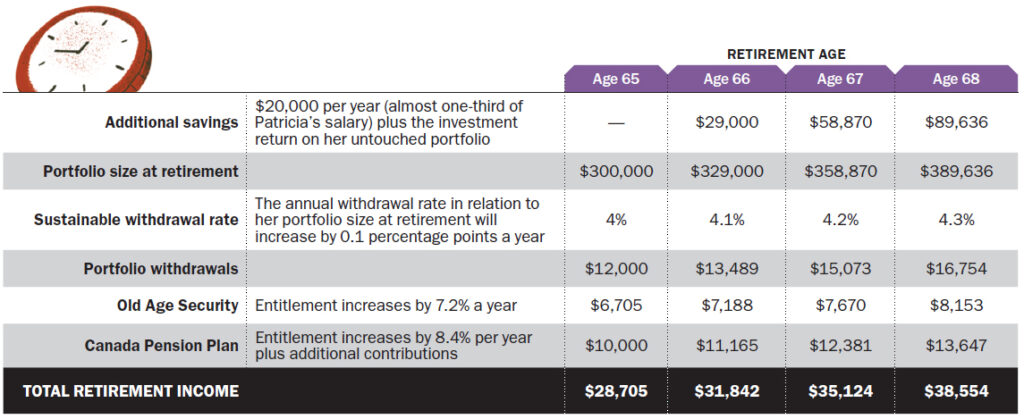

By waiting three years, Patricia saw her income jump up by almost one thirdIn that case, if Patricia is willing to save diligently while working another three years, we estimate she can boost her nest egg to about $390,000 and increase her pre-tax income to roughly $38,000 in today’s dollars. Since her basic needs are already covered, that increase of more than 30% in retirement income should provide substantial comfort. Of course, the enhanced income comes at a cost. You’ll have to work longer for a shorter retirement, so this isn’t a good choice if you don’t enjoy your job, or if you’re perfectly content to live on a more modest budget. Also, you’ll need to reach your late 60s in good health with attractive job prospects, so if you’re still young it’s best not to depend on this strategy. “It’s useful to have a margin of error,” advises Hamilton. Now let’s consider how each element of the strategy works in detail. Keep on super-saving Saving for retirement can have particular potency near the end of your working years. That’s because you’re likely to be near your peak in earnings and you’ve probably paid off your mortgage and are no longer supporting kids. As a result, you can grow your investment portfolio quickly with a few more years of super-saving. At this stage, most people with average or above-average salaries can save a quarter to a third of their gross salaries (including saving RRSP rebates) and sometimes more if they make saving a priority. Meanwhile, you can leave your nest egg untouched for a few more years. Even three more years of additional compounding can make a big difference before retirement, because by now your portfolio is likely to be larger than it’s ever been, thanks to your concentrated savings. When you were younger and your portfolio was smaller, the effect compounding had was modest: a 5% annual return would grow a $50,000 portfolio by about $7,900 in three years. But if your nest egg has reached $300,000, that same annual return will grow it by more than $47,000 over the same period, even if you’re not adding new money. Continuing to work a few years also provides some insurance in case you hit a big downturn in the market. In that case, your salary can cover your living costs and you won’t need to sell investments at beaten-down prices. In Patricia’s case, we assume she is able to save an additional $20,000 a year while she continues to work. To be conservative we also assume her untouched and growing portfolio will earn a real return (after inflation) of 3%. As a result, we estimate her nest egg will grow from $300,000 to around $390,000 in today’s dollars. That helps set the stage for higher income when she eventually retires. Bumping up drawdowns While working a few years past 65 will shorten your retirement, it should also provide additional means to help you enjoy it more. If you delay drawing down your investments you can bump up your withdrawal rate a little bit, because your nest egg won’t have to last as long. The traditional rule of thumb says if you retire at 65 and invest in a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds, you can withdraw about 4% of your initial nest egg each year, plus inflation adjustments, with little risk of running out of money. This is often referred to as a “sustainable withdrawal rate.” If you put off retirement a few years, I estimate you can increase that by a tenth of a percentage point (0.1%) for each year you delay. So if you retire at 68 instead, you could withdraw about 4.3% of your initial portfolio, plus inflation adjustments, with roughly the same assurance you won’t outlive your money. In Patricia’s case, instead of being able to withdraw 4% a year based on the initial value of a $300,000 portfolio at age 65, she should be able to withdraw 4.3% a year based on the initial value of a $390,000 portfolio at age 68. That should allow her to increase the annual withdrawals from $12,000 to more than $16,700 (plus subsequent inflation adjustments). While the risk of depleting your portfolio using a sustainable withdrawal rate is low, it’s not foolproof. If you want more certainty you won’t outlive your money, consider using some of your portfolio to purchase annuities. Like other investments, annuities also provide a better payoff if you delay when you start taking payouts. Many experts say the best time to buy them is in your early 70s. But if you’re particularly keen to get the assurance of steady income for life, buying annuities in your late 60s can still make sense. In our example, Patricia could buy a $300,000 annuity at age 65 and generate a yearly payout of $15,040 for life, based on a recent quote provided by Cannex Financial Exchanges Ltd. (This particular annuity includes annual payout increases of 2% designed to compensate for inflation and a 10-year guarantee period.) By waiting three additional years to age 68, Patricia could expect her $390,000 to buy an annuity with similar features that generates $21,555 a year for life, based on a current Cannex quote. (Women have higher life expectancy than men and therefore their annuity payout rates are lower. Also, the payout for a single person is higher than that for a couple because a joint annuity continues to pay out until the later of the two deaths.) While annuities are a viable option for Patricia, we’ve assumed she remains invested entirely in stocks and bonds for now. More government money Government benefits also pay you for waiting. If you delay their start past the standard retirement date—which is generally 65—your Old Age Security (OAS) entitlement increases by 7.2% a year and your Canada Pension Plan (CPP) benefit gets bumped up by 8.4% a year. In addition, by continuing to work and contribute to CPP past age 65, you may be able to increase your entitlement even further. In Patricia’s case, we assume she’s lived her entire life in Canada and is entitled to receive the maximum OAS at 65, which is currently $6,705 a year. By continuing to work and delaying her OAS by three years, she can increase her benefits to about $8,153 in today’s dollars at age 68.

Most people should apply for their cpp benefits as soon as they quit workWe assumed Patricia would be entitled to a CPP payout of $10,000 a year at age 65 (less than the maximum of $12,460 for retiring at that age). She could increase that entitlement to about $13,647 in today’s dollars by continuing to contribute while working another three years and starting CPP at age 68. While each of these individual factors may not seem like much, their combined effect can be huge. In Patricia’s case, retiring three years later would increase her retirement income by almost a third: from just under $29,000 to more than $38,000 a year. For many 60-somethings, that’s an improvement that’s well worth waiting for. After you retire After you’ve reaped the benefits of working longer, you have more choices for tapping your retirement income. Most Canadians start their government benefits immediately after they retire and draw on their investments for the remainder of their cash flow needs. In my view, that’s a good strategy for most middle-class Canadians without employer pensions. CPP and OAS provide a reliable base of income that usually covers many of your basic needs. You may also get additional income in the form of dividends and interest from your investments, so you won’t have to tap into much of your capital. That simplifies the process and makes it easy to ensure that portfolio drawdowns are sustainable. If your nest egg starts to appear a little dicey, you can cut back on the amounts you draw for discretionary spending. Deferring government benefits after retirement can also work, but requires more effort to manage. Usually you’ll take a bigger bite out of your portfolio initially, and then much less later on when you eventually start government benefits. You will need to make sure those initial drawdowns don’t get out of hand and deplete your savings. (You can also be too stingy, in which case your standard of living may suffer unnecessarily.) There’s no single right strategy, but those extra few years of work will give you more options for a comfortable retirement.

Getting paid to wait

How working past 65 can dramatically bolster a modest retirement

In this fictional example, Patricia reaches age 65 making $65,000 a year and has $300,000 in savings. She can dramatically increase her retirement income by working for another three years.

Notes: All amounts are in today’s dollars to reflect current purchasing power. Portfolio withdrawals are adjusted for inflation and government benefits are indexed automatically to inflation. Investment growth assumes real returns (adjusted for inflation) of 3% a year. We assume Patricia is eligible for maximum Old Age Security at age 65. Canadians born after March 1958 will get OAS at a later age. We assume Canada Pension Plan entitlement will increase by $300 annually for each additional year of contributing while working. (The actual impact on CPP entitlement will vary depending on personal circumstances from $0 to about $300 a year.)

David Aston, CFA, MA, writes about personal finance. You can send him questions, comments and suggested article topics at [email protected]Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email