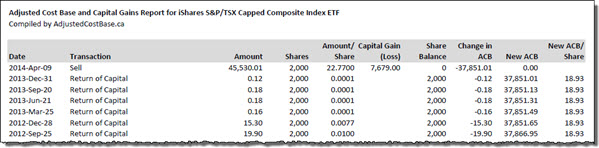

Calculating adjusted cost base: A case study

Calculating your ACB is not necessarily easy, but taking the time to do it properly could save you a significant amount of money.

Advertisement

Calculating your ACB is not necessarily easy, but taking the time to do it properly could save you a significant amount of money.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email