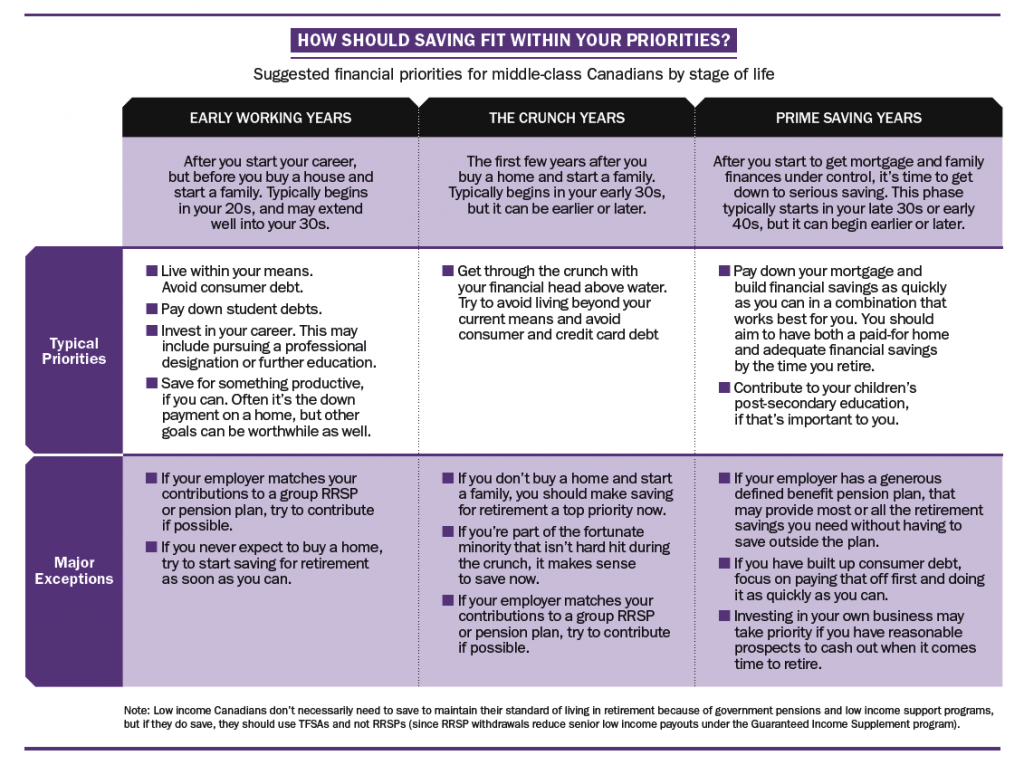

The right time to save for retirement

Your stage of life should help determine when you save

Advertisement

Your stage of life should help determine when you save

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email