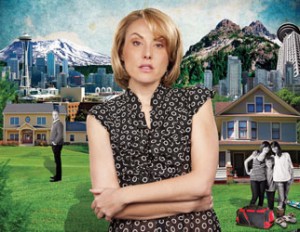

Family profile: Driven to destruction

Sabrina Mills is a hard-driving businesswoman who left her husband because he wasn’t making enough money. Now she’s raising three girls on her own, and she’s worse off than ever before.

Advertisement

Sabrina Mills is a hard-driving businesswoman who left her husband because he wasn’t making enough money. Now she’s raising three girls on her own, and she’s worse off than ever before.

Sabrina Mills never thought she’d find herself in this sorry situation. Two years ago, she thought leaving her husband would make things better. Instead, she’s now facing a bleak future. She has three daughters to raise on her own, practically no savings and a crushing $740,000 mortgage. The irony is she left her husband because he wasn’t making enough money. Now she has less than ever before.

Before 2008, the 48-year-old corporate trainer was earning $300,000 a year working for Fortune 500 companies all over the world. Meanwhile, her husband Jim stayed at home in Seattle, Washington, where he spent most of his time studying for his PhD and working at various low-paying jobs and internships.

The way Mills sees it, the problem in their relationship has always been Jim’s attitude towards money. (We’ve changed both their names to protect their privacy.) She says Jim, 52, never had any drive. Even though he’s highly qualified for dozens of six-figure-salary jobs and he’s well educated, Mills says he just never seemed to get anywhere. “Jim is like a child — totally lost. He never paid a bill or opened a bank statement. Until a couple of months ago I was still the one paying all the bills on our Washington home. I’ve always worn the pants in the family and I’m sick of it.”

Mills admits that in many ways, she’s Jim’s polar opposite. She’s career-oriented and ambitious, with a taste for the high life. “I love travel, adventure and fine food, and that costs money,” says Mills, who now lives in Vancouver with her 13-year-old twin daughters, Corinne and Lisa, and her younger daughter Maeve, 8. “I love to indulge myself and have a weakness for fine linens and carpets from Nepal. My parents always did Sears for clothes and furniture. Me, I love Italian style.”

The breaking point in the marriage came in the summer of 2008. Mills had accepted a lucrative six-month contract in Switzerland, and she decided she was taking her daughters with her. When she told Jim, he was livid. “We had a huge fight and I just lost it,” Mills recalls. “I told him that when I came back from Switzerland I’d be going back to Canada with the girls indefinitely.”

Mills has now put down roots in Vancouver, where her mother and two older brothers live. But when she left Jim, she left behind their only asset — a family home in Seattle that is valued at about $800,000, with a $400,000 mortgage. Mills says she’ll never see any money from that house.

“I have no money for expensive legal battles. My daughters will eventually get my share of the house when Jim dies. He’ll never sell while he’s alive.”

Mills thought she’d get further ahead without Jim holding her back, but over the last few months, she’s had a rude wake-up call. Her only investments are $37,000 in Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs), and $33,000 in a stock that was recommended by a friend. Her largest asset is the $460,000 equity stake she has in her Vancouver home. It was recently appraised at $1.2 million. “That sounds like a lot of money, but you wouldn’t believe how small the house is. Vancouver prices are insane.”

Worst of all, even with a substantial annual income of $150,000 from various consulting jobs, Mills is in the red by almost $5,000 every year. With a long list of financial goals that include saving for her retirement, paying for the kids’ university education, building a $50,000 emergency fund and paying down her mortgage, Mills isn’t sure what her priorities should be. “I don’t want to reach 50 as a tough bitch with no life and no money. I’ve worked hard all my life and feel I deserve better than this. Can you help me?”

Sabrina Mills grew up in Vancouver, the youngest of three kids. Her dad was a self-made businessman and her mom an executive assistant. They divorced when Mills was 13. “We were the poorest family in a rich neighbourhood because my dad would earn huge money one year and then lose it all the next. It was tragic. He was an alcoholic and died penniless.”

Mills credits her mother with pulling the family together. “My mom was a saver. I wish I could be more like her.” Still, Mills has always worked hard. At 14, she had a paper route and waitressed at the local pizza place. In 1982, she attended the University of British Columbia on a sports scholarship and graduated with her bachelor’s degree in psychology four years later.

Jim, meanwhile, spent his early childhood in Germany. He was raised in a well-off but frugal family. His mom died when he was 8 and his dad remarried. That’s when Jim moved to Seattle, his stepmother’s hometown. According to Mills, Jim’s lack of financial ambition can be linked all the way back to his father’s second wife. “Jim’s stepmother keeps her budget to the absolute penny,” Mills says. “She’ll sew things for my kids and then give me a bill for the thread and buttons. That’s how cheap she is.”

Mills worked a couple of years in human resources and then completed a master’s degree in Organizational Psychology in Boston in 1989. She moved to London, England, a year later on a three-year contract for a peacekeeping organization. That’s where she met Jim, who was in London working towards his doctorate in genetics. “He was smart, generous and had dozens of friends,” says Mills. “I liked him right away.”

In 1995, the couple decided to get married and move back to Seattle. “Jim got a job as a research assistant at a local university and it paid almost nothing,” says Mills. “Over the years it was my salary, usually between $150,000 and $300,000, that paid for everything — the wedding, the house, his student loans and about $50,000 in other debt that Jim had accumulated prior to marrying me. He has no clue about money.”

Mills soon got pregnant with twins, but rather than being a joyous time, it became a dark period in her life. She had asked Jim to take a job that provided medical insurance, but he refused. “He couldn’t understand why I was so irate. The twins were premature, and I couldn’t work, and he had just taken a job making $28,000. The poverty line was $29,000. He just didn’t care.”

Just four months later, Mills was back at work doing full-time consulting. Because she didn’t have a green card, all of her assignments came from Europe. She took the twins with her wherever she went, along with her mother, who became their caregiver when Mills was working.

Mills says a lot of the money she made in those early days went into renovations for a rambling ranch house she and Jim bought in Seattle in 1998. “It was dumpy and all we could afford,” says Mills. “Over the years we put $300,000 into renovations.” Mills also managed to put aside $250,000 for her retirement, and the same amount in a retirement account for Jim, while the rest was spent on the good life. “I like to spend, and I don’t buy cheap stuff,” Mills admits. “It’s only now that I’m starting to have some regrets over the lifestyle choices I made.”

Mills’s daughter Maeve was born in 2002, and the stress of family life got worse. When Mills announced she was leaving for Switzerland with the girls, things came to a head. She and Jim had a huge fight, and after the six-month contract was up, she never went home to Seattle: she settled in Vancouver with the kids.

Mills used the $250,000 she’d earmarked for retirement as a down payment on her Vancouver home, which cost $995,000. (She forfeited the $250,000 that she had saved for Jim’s retirement when she left him.) Right now, her largest annual expense is the whopping $52,200 a year that she spends on mortgage payments and property taxes. The mortgage is at 4.2%, with two years left on the term, on track to be paid off in 25 years. She is also paying $19,000 in fees for the girls’ dancing, hockey and skiing lessons.

To help relieve some of the financial pressure, Mills is considering paying a $15,000 penalty to break her mortgage and move it to another financial institution that would offer her a personal line of credit that she could tap into for emergencies. “Maybe that type of account would save me money in the long run.”

For now, Mills has dropped all legal proceedings against Jim for a divorce. She simply has no money to pursue it. But he’s still asking for help to pay his bills. “I’m in a trapped place emotionally. I don’t even know how to talk to Jim anymore. I’m at the point where I realize I can’t rely on anyone but myself. But I’m strong, and with a plan I know I can make my new life work.”

What the experts say

If Sabrina Mills doesn’t start planning for her future right away, she won’t be able to retire a day before 70. “The truth is that she’s in over her head,” says Alfred Feth, a fee-only planner in Waterloo, Ont. “She’s house-rich, cash-poor and living beyond her means. She has to make tough choices and learn to live modestly.”

Sally Palaian, a clinical psychologist and author of Spent: Break the Buying Obsession and Discover Your True Worth, agrees, stressing that Mills will have to drastically change her money habits to stay afloat. “I’m sure Sabrina was initially attracted to Jim for all the same reasons that she hates him now,” says Palaian. “But Jim has avoided money issues all his life. She needs to cut the financial umbilical cord and not give in to any more of his requests for money. Otherwise he will drain her forever.”

Here’s what the experts recommend.

Cut the kids’ activities

Mills can’t afford $19,000 for her kids’ sports and lessons. If she cuts back to $3,000 a year, she can save $16,000 annually that can go directly into an RRSP. “She’s in a high tax bracket and has to mitigate her taxes,” says Lenore Davis, a certified financial planner with Dixon, Davis & Co. in Victoria. “Her tax rebate should also go towards making future RRSP contributions.” If Mills contributes $20,000 annually to her RRSP and gets a modest 5% annual return, she will reach age 60 with a $334,000 nest egg, plus the equity in her home — a comfortable amount.

Cut other expenses by $4,700

Mills is over budget by $4,700 annually. She needs to cut other expenses to bring her annual shortfall down to zero. She should trim her gift expenses, vacation, cleaning lady fees, clothes and haircuts, and miscellaneous expenses until the budget is balanced.

No more RESP contributions

The government will lend students money to attend university, but it won’t lend Mills money to save for her retirement. “The $37,000 in RESP money is all she can afford to give the kids,” says Davis. “It’s enough. If they want a university education, they’ll find a way.”

Cash in the stock

She should sell the $33,000 she has in stocks and put at least $15,000 of that money into an emergency fund. “Given her financial position, there’s no benefit to holding on to the stock,” says Feth. “Selling it to create an emergency fund will give her peace of mind.”

Forget about refinancing

Even though Mills desperately wants a new mortgage with a built-in line of credit, Vince Gaetano, principal mortgage broker with MonsterMortgage.ca in Markham, Ont., says it would be a terrible idea. He ran the numbers on the deal that Mills is considering, and says the new mortgage would cost her not only the $15,000 penalty, but also thousands more each year in extra interest payments. “She’s tapped out and looking for an avenue to access cash when she should be paying down her mortgage or beefing up her retirement savings,” he says.

Consider downsizing

Mills should move to a less expensive place as soon as she can — perhaps when her twins leave for university in four years. She can easily buy a nice condo for herself and her youngest daughter in Vancouver for $600,000 or so. If she isn’t ready to downsize then, she should certainly consider it in 10 years when Maeve will also be gone. “She can sell her house and downsize, or return to Europe, where she can spend the last few years of her career earning $200,000 to $300,000 annually,” says Feth. “If she saves much of her income from those final working years and banks the proceeds from the sale of her home, she’ll reach 65 with well over $1 million.”

Get counseling

Mills and Jim should spend $4,000 for six months of couples therapy. “Even if they never reconcile, they have to learn to communicate calmly and effectively with each other for the sake of their daughters,” says Palaian. “In the end, that’s what will really benefit the family most.”

Sabrina Mills never thought she’d find herself in this sorry situation. Two years ago, she thought leaving her husband would make things better. Instead, she’s now facing a bleak future. She has three daughters to raise on her own, practically no savings and a crushing $740,000 mortgage. The irony is she left her husband because he wasn’t making enough money. Now she has less than ever before.

Before 2008, the 48-year-old corporate trainer was earning $300,000 a year working for Fortune 500 companies all over the world. Meanwhile, her husband Jim stayed at home in Seattle, Washington, where he spent most of his time studying for his PhD and working at various low-paying jobs and internships.

The way Mills sees it, the problem in their relationship has always been Jim’s attitude towards money. (We’ve changed both their names to protect their privacy.) She says Jim, 52, never had any drive. Even though he’s highly qualified for dozens of six-figure-salary jobs and he’s well educated, Mills says he just never seemed to get anywhere. “Jim is like a child — totally lost. He never paid a bill or opened a bank statement. Until a couple of months ago I was still the one paying all the bills on our Washington home. I’ve always worn the pants in the family and I’m sick of it.”

Mills admits that in many ways, she’s Jim’s polar opposite. She’s career-oriented and ambitious, with a taste for the high life. “I love travel, adventure and fine food, and that costs money,” says Mills, who now lives in Vancouver with her 13-year-old twin daughters, Corinne and Lisa, and her younger daughter Maeve, 8. “I love to indulge myself and have a weakness for fine linens and carpets from Nepal. My parents always did Sears for clothes and furniture. Me, I love Italian style.”

The breaking point in the marriage came in the summer of 2008. Mills had accepted a lucrative six-month contract in Switzerland, and she decided she was taking her daughters with her. When she told Jim, he was livid. “We had a huge fight and I just lost it,” Mills recalls. “I told him that when I came back from Switzerland I’d be going back to Canada with the girls indefinitely.”

Mills has now put down roots in Vancouver, where her mother and two older brothers live. But when she left Jim, she left behind their only asset — a family home in Seattle that is valued at about $800,000, with a $400,000 mortgage. Mills says she’ll never see any money from that house.

“I have no money for expensive legal battles. My daughters will eventually get my share of the house when Jim dies. He’ll never sell while he’s alive.”

Mills thought she’d get further ahead without Jim holding her back, but over the last few months, she’s had a rude wake-up call. Her only investments are $37,000 in Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs), and $33,000 in a stock that was recommended by a friend. Her largest asset is the $460,000 equity stake she has in her Vancouver home. It was recently appraised at $1.2 million. “That sounds like a lot of money, but you wouldn’t believe how small the house is. Vancouver prices are insane.”

Worst of all, even with a substantial annual income of $150,000 from various consulting jobs, Mills is in the red by almost $5,000 every year. With a long list of financial goals that include saving for her retirement, paying for the kids’ university education, building a $50,000 emergency fund and paying down her mortgage, Mills isn’t sure what her priorities should be. “I don’t want to reach 50 as a tough bitch with no life and no money. I’ve worked hard all my life and feel I deserve better than this. Can you help me?”

Sabrina Mills grew up in Vancouver, the youngest of three kids. Her dad was a self-made businessman and her mom an executive assistant. They divorced when Mills was 13. “We were the poorest family in a rich neighbourhood because my dad would earn huge money one year and then lose it all the next. It was tragic. He was an alcoholic and died penniless.”

Mills credits her mother with pulling the family together. “My mom was a saver. I wish I could be more like her.” Still, Mills has always worked hard. At 14, she had a paper route and waitressed at the local pizza place. In 1982, she attended the University of British Columbia on a sports scholarship and graduated with her bachelor’s degree in psychology four years later.

Jim, meanwhile, spent his early childhood in Germany. He was raised in a well-off but frugal family. His mom died when he was 8 and his dad remarried. That’s when Jim moved to Seattle, his stepmother’s hometown. According to Mills, Jim’s lack of financial ambition can be linked all the way back to his father’s second wife. “Jim’s stepmother keeps her budget to the absolute penny,” Mills says. “She’ll sew things for my kids and then give me a bill for the thread and buttons. That’s how cheap she is.”

Mills worked a couple of years in human resources and then completed a master’s degree in Organizational Psychology in Boston in 1989. She moved to London, England, a year later on a three-year contract for a peacekeeping organization. That’s where she met Jim, who was in London working towards his doctorate in genetics. “He was smart, generous and had dozens of friends,” says Mills. “I liked him right away.”

In 1995, the couple decided to get married and move back to Seattle. “Jim got a job as a research assistant at a local university and it paid almost nothing,” says Mills. “Over the years it was my salary, usually between $150,000 and $300,000, that paid for everything — the wedding, the house, his student loans and about $50,000 in other debt that Jim had accumulated prior to marrying me. He has no clue about money.”

Mills soon got pregnant with twins, but rather than being a joyous time, it became a dark period in her life. She had asked Jim to take a job that provided medical insurance, but he refused. “He couldn’t understand why I was so irate. The twins were premature, and I couldn’t work, and he had just taken a job making $28,000. The poverty line was $29,000. He just didn’t care.”

Just four months later, Mills was back at work doing full-time consulting. Because she didn’t have a green card, all of her assignments came from Europe. She took the twins with her wherever she went, along with her mother, who became their caregiver when Mills was working.

Mills says a lot of the money she made in those early days went into renovations for a rambling ranch house she and Jim bought in Seattle in 1998. “It was dumpy and all we could afford,” says Mills. “Over the years we put $300,000 into renovations.” Mills also managed to put aside $250,000 for her retirement, and the same amount in a retirement account for Jim, while the rest was spent on the good life. “I like to spend, and I don’t buy cheap stuff,” Mills admits. “It’s only now that I’m starting to have some regrets over the lifestyle choices I made.”

Mills’s daughter Maeve was born in 2002, and the stress of family life got worse. When Mills announced she was leaving for Switzerland with the girls, things came to a head. She and Jim had a huge fight, and after the six-month contract was up, she never went home to Seattle: she settled in Vancouver with the kids.

Mills used the $250,000 she’d earmarked for retirement as a down payment on her Vancouver home, which cost $995,000. (She forfeited the $250,000 that she had saved for Jim’s retirement when she left him.) Right now, her largest annual expense is the whopping $52,200 a year that she spends on mortgage payments and property taxes. The mortgage is at 4.2%, with two years left on the term, on track to be paid off in 25 years. She is also paying $19,000 in fees for the girls’ dancing, hockey and skiing lessons.

To help relieve some of the financial pressure, Mills is considering paying a $15,000 penalty to break her mortgage and move it to another financial institution that would offer her a personal line of credit that she could tap into for emergencies. “Maybe that type of account would save me money in the long run.”

For now, Mills has dropped all legal proceedings against Jim for a divorce. She simply has no money to pursue it. But he’s still asking for help to pay his bills. “I’m in a trapped place emotionally. I don’t even know how to talk to Jim anymore. I’m at the point where I realize I can’t rely on anyone but myself. But I’m strong, and with a plan I know I can make my new life work.”

What the experts say

If Sabrina Mills doesn’t start planning for her future right away, she won’t be able to retire a day before 70. “The truth is that she’s in over her head,” says Alfred Feth, a fee-only planner in Waterloo, Ont. “She’s house-rich, cash-poor and living beyond her means. She has to make tough choices and learn to live modestly.”

Sally Palaian, a clinical psychologist and author of Spent: Break the Buying Obsession and Discover Your True Worth, agrees, stressing that Mills will have to drastically change her money habits to stay afloat. “I’m sure Sabrina was initially attracted to Jim for all the same reasons that she hates him now,” says Palaian. “But Jim has avoided money issues all his life. She needs to cut the financial umbilical cord and not give in to any more of his requests for money. Otherwise he will drain her forever.”

Here’s what the experts recommend.

Cut the kids’ activities

Mills can’t afford $19,000 for her kids’ sports and lessons. If she cuts back to $3,000 a year, she can save $16,000 annually that can go directly into an RRSP. “She’s in a high tax bracket and has to mitigate her taxes,” says Lenore Davis, a certified financial planner with Dixon, Davis & Co. in Victoria. “Her tax rebate should also go towards making future RRSP contributions.” If Mills contributes $20,000 annually to her RRSP and gets a modest 5% annual return, she will reach age 60 with a $334,000 nest egg, plus the equity in her home — a comfortable amount.

Cut other expenses by $4,700

Mills is over budget by $4,700 annually. She needs to cut other expenses to bring her annual shortfall down to zero. She should trim her gift expenses, vacation, cleaning lady fees, clothes and haircuts, and miscellaneous expenses until the budget is balanced.

No more RESP contributions

The government will lend students money to attend university, but it won’t lend Mills money to save for her retirement. “The $37,000 in RESP money is all she can afford to give the kids,” says Davis. “It’s enough. If they want a university education, they’ll find a way.”

Cash in the stock

She should sell the $33,000 she has in stocks and put at least $15,000 of that money into an emergency fund. “Given her financial position, there’s no benefit to holding on to the stock,” says Feth. “Selling it to create an emergency fund will give her peace of mind.”

Forget about refinancing

Even though Mills desperately wants a new mortgage with a built-in line of credit, Vince Gaetano, principal mortgage broker with MonsterMortgage.ca in Markham, Ont., says it would be a terrible idea. He ran the numbers on the deal that Mills is considering, and says the new mortgage would cost her not only the $15,000 penalty, but also thousands more each year in extra interest payments. “She’s tapped out and looking for an avenue to access cash when she should be paying down her mortgage or beefing up her retirement savings,” he says.

Consider downsizing

Mills should move to a less expensive place as soon as she can — perhaps when her twins leave for university in four years. She can easily buy a nice condo for herself and her youngest daughter in Vancouver for $600,000 or so. If she isn’t ready to downsize then, she should certainly consider it in 10 years when Maeve will also be gone. “She can sell her house and downsize, or return to Europe, where she can spend the last few years of her career earning $200,000 to $300,000 annually,” says Feth. “If she saves much of her income from those final working years and banks the proceeds from the sale of her home, she’ll reach 65 with well over $1 million.”

Get counseling

Mills and Jim should spend $4,000 for six months of couples therapy. “Even if they never reconcile, they have to learn to communicate calmly and effectively with each other for the sake of their daughters,” says Palaian. “In the end, that’s what will really benefit the family most.”

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email